Another funny take on the confusion of weather and climate…

| The Daily Show With Jon Stewart | Mon – Thurs 11p / 10c | |||

| Unusually Large Snowstorm | ||||

|

||||

Another funny take on the confusion of weather and climate…

| The Daily Show With Jon Stewart | Mon – Thurs 11p / 10c | |||

| Unusually Large Snowstorm | ||||

|

||||

| The Colbert Report | Mon – Thurs 11:30pm / 10:30c | |||

| We’re Off to See the Blizzard | ||||

|

||||

Interesting insights from pollster Frank Luntz, via Reuters:

“If you really want to scare Americans it’s not about glaciers that are melting or the struggle of the polar bear,” said the pollster and political adviser Frank Luntz, most known for his work with Republicans.

“What scares Americans is the idea that this great technological industry will be developed in China or India rather than America,” said Luntz, who once advised former President George W. Bush’s administration to emphasize that there was a lack of scientific certainty about climate change.

…

Luntz said polls his company conducted late last year showed that a combined 65 percent of respondents stated that climate change exists and action needs to be taken, or that the science was not settled but people should explore ways to cut emissions and adopt clean energy. “This is true of Republicans and Democrats alike,” he said.

…

Backers of the cap-and-trade bill have emphasized climate science too much, and the potential positive results from a clean-energy bill — domestic jobs, a healthier environment, and potentially less money sent to the Middle East for oil — too little, Luntz said.

Wording is important in drumming up support for the bill, he added. Backers should emphasize it would create “American” jobs rather than “green” jobs, while Americans want “reliable” technology more than “smart” technology, he said.

Poll respondents who were Democrats or Republicans believed the most important environmental and economic goal for the United States should be cutting dependence on foreign fuel and halting pollution of the air and water. Ending climate change came in last of the 10 priorities in that category.

Hat tip to Travis Franck.

A critique of Lindzen & Choi’s 2009 paper has just been published, debunking the notion of strong negative temperature feedback in the tropics. I had noticed that its statistical method of identifying intervals in a time series was flawed, and that models cited appeared to sometimes lack volcanic forcings, rendering correlations meaningless. I’m happy to see those observations confirmed, and a few other problems raised. (I’m happy that I was right, not that climate sensitivity is higher than Lindzen & Choi suggest, which would be good for the planet.) I haven’t read the details of the critiques, so I can’t say whether this really closes the book on the question, but it at least indicates that the original work was a bit sloppy. Since Lindzen is one of the few contrarians who knows what he’s doing, and it’s useful to have such people around, I wish he would focus less on WSJ editorials and more on scholarship.

Check out my guest post at Inside-Out China.

Over Christmas, with little fanfare, two new approaches to climate legislation were introduced, perhaps in response to the possibility that Boxer-Kerry’s prospects are dimming. VentureBeat has a summary. The Kerry-Lieberman-Graham approach is just a “framework” and too vague for me to sink my teeth into. The Cantwell-Collins CLEAR act on the other hand is a real bill. Unlike the 1000-page ACES (Waxman-Markey), it’s just about cap & trade, so it’s refreshingly brief – 39 pages. CLEAR sets targets,

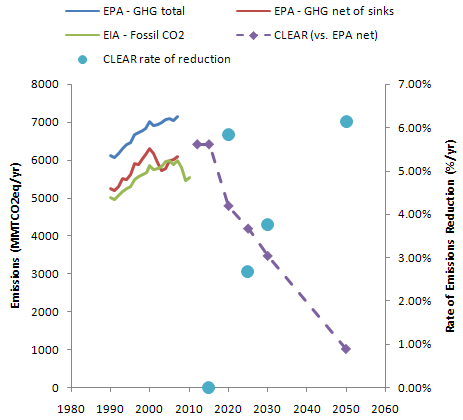

As in Waxman-Markey and other bills, the target trajectory is mostly linear. That actually doesn’t make much sense, because it implies a much greater proportional effort late in the game. Emissions reductions finish at >6%/year. If GDP growth is 3%/year, that implies a final intensity reduction rate of >9%/year, which is fairly delusional. Unlike Waxman-Markey, which is strictly linear, the first three years are flat, then there’s a race to the 2020 target. It’s good to harvest the low-hanging fruit quickly, but the 2015-2020 trajectory seems a little sporty.

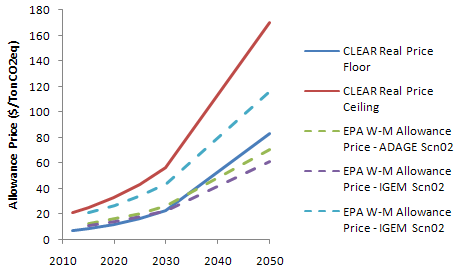

The real emissions trajectory is unknown, because there’s a safety valve price ceiling and floor, initially set at 7 to 21 $/tonCO2eq, and rising at the real interest rate, plus and minus 0.5%, respectively. The resulting prices neatly bracket EPA’s expectations for Waxman-Markey without international offsets (Scn07 on graph):

Source: EPA W-M analysis.

CLEAR is upstream, covering fuels at the minemouth, wellhead, import terminal, etc. This strikes me as a big advantage administratively and improves coverage as well. Offsets, funded by a set-aside from auction revenues, play a much smaller role, which is OK, because with better coverage there won’t be as big a market. International offsets are also assumed to play a much smaller role (a few % of reductions, vs. roughly half of W-M reductions). That makes the true target trajectory much more aggressive, and raises expected permit prices a lot. Whether this is good or bad is ambiguous; one drawback is that there’s potentially less “carrot” for developing countries, and less funding for forestry.

Unlike Waxman-Markey, CLEAR allocates most (75%) permits to citizens as “shares”. That’s bad news for coal-fired electric utilities, but possibly good news for low income residents of coal-intensive areas. My guess is that the totally flat distribution of revenue would more than compensate for regional inequities for the bottom quintile, who would come out ahead. The remaining permits go to a “CERT” fund for worker, business, and community transitions, stranded assets, targeted relief for energy-intensive industries exporting to countries without emissions controls, R&D, offsets and other usual suspects. There’s room for a lot of good here, but also a lot of pork. I think it would make sense to partially phase out the fund in the future, as its revenues would likely rise beyond the need.

Like W-M, CLEAR includes a border adjustment (effectively a tariff on the embodied carbon content of imports). This, plus the potential trade measures in CERT, should make labor happy and infuriate WTO partners like China.

Strategically, CLEAR seems to leave more of the detailed design of the market and related mechanisms to the executive branch. I think that’s a good thing. It’s impossible to have a sensible debate about a piece of legislation the size of the Oxford dictionary. Add in the fact that this proposal is much closer to economic ideals for a cap & trade (upstream coverage, flat rebates, safety valves) and I’m liking this a lot better than ACES.

Grist muses over the possibility that abrupt climate change in the not-too-distant future might trigger a chaotic response.

One morning in the not too distant future, you might wake up and walk to your mailbox. The newspaper is in there and it’s covered with shocking headlines: Coal Plants Shut Down! Airline Travel Down 50 Percent! New Federal Carbon Restrictions in Place! Governor Kicked Out of Office for Climate Indolence!

…

It is exactly these economic impacts that the Glenn Becks and the Rush Limbaughs fear we’ll impose on ourselves through restrictive government regulation of energy and carbon emissions. Ironically, a “no action” approach today actually makes a climate panic much more likely over time. What we’re describing would be popularly driven, not fueled by governments or policy wonks. It would be the direct result of free will, democracy, autonomy and the information superhighway. All these forces would accelerate, not mitigate, the greatest “Aha!” moment in the history of the human species. Imagine the sub-prime mortgage bubble pop multiplied a hundred fold.

I hesitate to argue for rationality (certainly our current climate and energy policies aren’t), but I think the physics of climate and human nature do not favor this outcome. The pain of economic dislocation is immediate. At the point of abrupt climate change, on the other hand, it would be evident that we’re stuck with it for decades, because there’s no quick way to reverse the accumulation of GHGs in the atmosphere. Even lowering emissions to zero overnight would have only a gradual climatic effect. Since that would be evident to everyone, especially those with GHG-intensive assets, it seems unlikely that rapid controls would emerge, and likely that they would be reversed when their pain was felt too keenly. I suppose macroeconomic feedbacks might make the damage irreversible, or countries might start launching cruise missiles at each others’ coal-fired power plants, but those seem like long odds.

More likely, I suspect, is that panic would yield enormous pressure to pursue geoengineering options – the only real prospect for a quick reversal of radiative imbalance. If, at that point, we’ve triggered abrupt climate changes without warning, it seems likely that our understanding of geoengineering side-effects would still be half-baked. The nasty side effects that might emerge from efforts under such circumstances strikes me as the greater threat of climate panic.

Setting climate aside, another panic scenario that should concern fossil-fired asset owners is a major oil supply disruption. That could de facto shut down emissions and use through high prices, no political will power required.

I’ve been looking over the final COP15 decision (here, for now). So far it all looks nonbinding. I was curious how some of the players are reacting.

“Today’s agreement leaves the U.S. in control of its own destiny. … As President Obama said today, strong action on climate change is in America’s national interest.” — EDF’s Fred Krupp, Dec. 18, 2009

“The world’s nations have come together and concluded a historic–if incomplete–agreement to begin tackling global warming. Tonight’s announcement is but a first step and much work remains to be done in the days and months ahead in order to seal a final international climate deal that is fair, binding, and ambitious. It is imperative that negotiations resume as soon as possible.

…

“The agreement reached here has all the ingredients necessary to construct a final treaty–a mitigation target of 2 degrees Celsius, nationally appropriate action plans, a mechanism for international climate finance, and transparency with regard to national commitments. President Obama has made much progress in past 11 months and it now appears that the U.S.–and the world–is ready to do the hard work necessary to finish what was started here in Copenhagen.

Copenhagen a cop-out

Two years have passed since world leaders promised all of us a deal to stop climate change. After two weeks of UN negotiations, politicians breezed in, had dinner with the Queen, a three hour lunch, took some photos, and then delivered what could only be described as the 24-hour Head of State tourist brochure of Copenhagen instead of a climate treaty.

League of Conservation Voters (via email)

I’m in Copenhagen and President Obama has just wrapped up a press conference here announcing that a meaningful climate deal has been reached. While there is still much work to be done, the deal reached is a breakthrough for international climate cooperation and provides a path forward towards a binding global treaty in 2010.

Significantly, the United States and China will – for the first time – both be at the table, working to tackle the historic challenge of global climate change. Additionally, the deal allows for more transparency, as developed and developing countries have now agreed to list their national actions and commitments regarding greenhouse gas reductions.

“We agree with President Obama on the importance of addressing global climate change. However, Congress’s leading proposals could destroy millions of jobs, drive up fuel prices, and, by shifting much of our refining capacity abroad (along with refinery greenhouse gas emissions), substantially increase our reliance on foreign supplies of gasoline, diesel and other petroleum fuels. Worse, the president’s own EPA is poised to issue an expansive regimen of climate regulations that could cripple business growth and job creation, dimming employment hopes for 15 million now out-of-work Americans.

…

“Public support for government climate change proposals has waned. It’s time for all stakeholders to come together to craft a fair, efficient, market-based climate change strategy that minimizes the burden on consumers and jobs.”

Can’t find a final reaction yet: USCAP, WWF, ECF, and many others. Seems like the press releases haven’t all hit yet.

Update 12/22: a nice summary at Roger Peilke’s blog.

A lot of the draft agreements floating around reference a principle of equity in cumulative emissions budgets. For example, the latest AWG-LCA draft,

A long-term aspirational and ambitious global goal for emission reductions, as part of the shared vision for long-term cooperative action, should be based on the best available scientific knowledge and supported by medium-term goals for emission reductions, taking into account historical responsibilities and an equitable share in the atmospheric space;

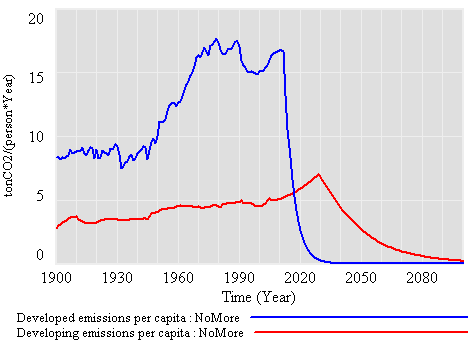

That’s a nice sentiment, but the goals expressed here are not compatible. If you take “aspirational and ambitious” to mean 55oppm – much less stringent then a 1.5 or 2C target – we’re already halfway or more through civilization’s cumulative emissions budget. Most of the historic emissions occurred in the 20th century. The rest will happen this century. The problem is, there are a lot more people around this century than last. Therefore, this century’s remaining emissions budget just isn’t big enough to make up for historic inequity in emissions, even if you allocate it all to the developing world.

For example, here’s a scenario in which the developed world stops emitting almost immediately – essentially abandoning its GHG-intensive capital stock – while the developing world pursues a trajectory consistent with a global 50% cut by 2050. Per capita emissions convergence and reversal happens right away:

Continue reading “You can't fix emissions inequity with more emissions”

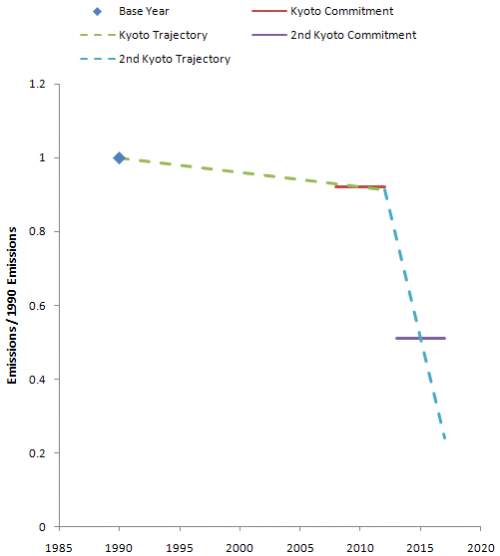

I’ve added the Dec. 16 Kyoto Protocol working group draft to my summary table.

There’s not much to report with respect to the global outcome. Most of the detail is focused on Annex I (developed) country commitments. There are so many options and brackets in the text that it’s hard to draw any concrete conclusions about the implied emissions trajectory.

There’s possibly an interesting disconnect around characterization of the second round of targets. Currently there are a number of options included in bracketed text. First, the endpoint could be either 2017 or 2020. Second, various options suggest a range of cuts between 15% and 49% below 1990. This range corresponds roughly with the range typically cited as providing a decent chance of hitting a 2C target (see AR4 WG3 Ch. 13 box 13.7, pg. 776, for example).

If you think back to the first Kyoto agreement, countries committed to small cuts relative to 1990 for a commitment period from 2008 to 2012. For the EU, with an 8% cut, that meant averaging 92% of 1990 emissions over the commitment period. If you imagine that emissions fall along a linear path from 1990, that means that emissions at the midpoint (2010) would be 92% of 1990, and emissions would be a little higher prior to that, and lower after. Because the slope from 1990 through 2012 is shallow, a viable trajectory would include a 7% cut in 2008 and 9% in 2012. No big deal.

However, for the next commitment period, the slope is a very big deal. The deepest cut in the AWG-KP draft is 49% for the developed world. I suspect that number is anchored on upper end of the AR4 2C range (25-40%), moved up a bit. 49% still sounds plausible. But there’s a problem: to achieve a 49% average over 2013-2020, starting from a 9% cut in 2012, you’d have to do one of two things: reduce emissions an additional 37% overnight, then keep them there (basically impossible), or reduce emissions by 13 percentage points per year, arriving at a cut of 76% in 2017. That’s a year-on-year reduction rate of 15 to 35% per year. That’s pretty tough going, given that, even if you never build another bit of carbon-emitting capital, natural turnover takes you down at 2 to 5% per year.

I’m all for strong targets, but abandoning capital at 10% per year is going to be a tough sell. It’s not clear to me that this is intentional. I think it’s quite possible that misperception of the dynamics of a target accumulated over an interval leads to false conflict, as desire to achieve a point goal (e.g., -40% in 2020) is confused with a much more stringent goal over a long interval.