Roger Pielke Jr. poses a carbon price paradox:

The carbon price paradox is that any politically conceivable price on carbon can do little more than have a marginal effect on the modern energy economy. A price that would be high enough to induce transformational change is just not in the cards. Thus, carbon pricing alone cannot lead to a transformation of the energy economy.

Advocates for a response to climate change based on increasing the costs of carbon-based energy skate around the fact that people react very negatively to higher prices by promising that action won’t really cost that much. … If action on climate change is indeed “not costly” then it would logically follow the only reasons for anyone to question a strategy based on increasing the costs of energy are complete ignorance and/or a crass willingness to destroy the planet for private gain. … There is another view. Specifically that the current ranges of actions at the forefront of the climate debate focused on putting a price on carbon in order to motivate action are misguided and cannot succeed. This argument goes as follows: In order for action to occur costs must be significant enough to change incentives and thus behavior. Without the sugarcoating, pricing carbon (whether via cap-and-trade or a direct tax) is designed to be costly. In this basic principle lies the seed of failure. Policy makers will do (and have done) everything they can to avoid imposing higher costs of energy on their constituents via dodgy offsets, overly generous allowances, safety valves, hot air, and whatever other gimmick they can come up with.

His prescription (and that of the Breakthrough Institute) is low carbon taxes, reinvested in R&D:

We believe that soon-to-be-president Obama’s proposal to spend $150 billion over the next 10 years on developing carbon-free energy technologies and infrastructure is the right first step. … a $5 charge on each ton of carbon dioxide produced in the use of fossil fuel energy would raise $30 billion a year. This is more than enough to finance the Obama plan twice over.

… We would like to create the conditions for a virtuous cycle, whereby a small, politically acceptable charge for the use of carbon emitting energy, is used to invest immediately in the development and subsequent deployment of technologies that will accelerate the decarbonization of the U.S. economy.

…

Stop talking, start solving

As the nation begins to rely less and less on fossil fuels, the political atmosphere will be more favorable to gradually raising the charge on carbon, as it will have less of an impact on businesses and consumers, this in turn will ensure that there is a steady, perhaps even growing source of funds to support a process of continuous technological innovation.

This approach reminds me of an old joke:

Lenin, Stalin, Khrushchev and Brezhnev are travelling together on a train. Unexpectedly the train stops. Lenin suggests: “Perhaps, we should call a subbotnik, so that workers and peasants fix the problem.” Kruschev suggests rehabilitating the engineers, and leaves for a while, but nothing happens. Stalin, fed up, steps out to intervene. Rifle shots are heard, but when he returns there is still no motion. Brezhnev reaches over, pulls the curtain, and says, “Comrades, let’s pretend we’re moving.”

I translate the structure of Pielke’s argument like this:

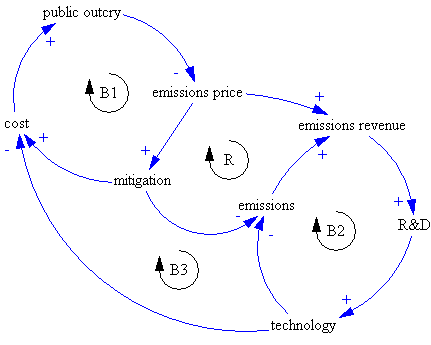

Implementation of a high emissions price now would be undone politically (B1). A low emissions price triggers a virtuous cycle (R), as revenue reinvested in technology lowers the cost of future mitigation, minimizing public outcry and enabling the emissions price to go up. Note that this structure implies two other balancing loops (B2 & B3) that serve to weaken the R&D effect, because revenues fall as emissions fall.

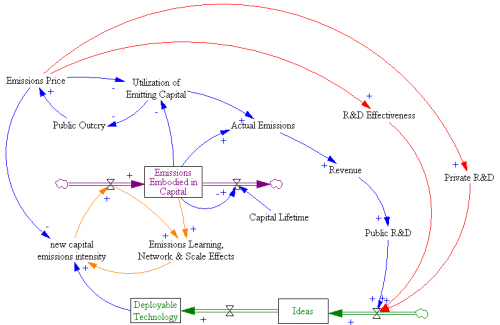

If you elaborate on the diagram a bit, you can see why the technology-led strategy is unlikely to work:

First, there’s a huge delay between R&D investment and emergence of deployable technology (green stock-flow chain). R&D funded now by an emissions price could take decades to emerge. Second, there’s another huge delay from the slow turnover of the existing capital stock (purple) – even if we had cars that ran on water tomorrow, it would take 15 years or more to turn over the fleet. Buildings and infrastructure last much longer. Together, those delays greatly weaken the near-term effect of R&D on emissions, and therefore also prevent the virtuous cycle of reduced public outcry due to greater opportunities from getting going. As long as emissions prices remain low, the accumulation of commitments to high-emissions capital grows, increasing public resistance to a later change in direction.

Emissions embodied in the capital stock create powerful learning, network, and scale effects (orange). As long as the emissions price is low, every unit of high-emissions capital installed moves high-emitting capital producers down the learning curve, while low-emitting producers languish. Also, the infrastructure, like roads and fueling stations for conventional vehicles, remains locked in to a high emissions mode. These are extremely powerful positive feedbacks, and they can prevent implementation of new technologies even where they are intrinsically better than existing ones. They’re matched by a similar set of loops on the social side (not shown) that reinforce high-emissions lifestyle preferences.

While a low emissions price can fund public R&D, it does little for private R&D. Without a significant price, there’s little profit motive for developing low-emissions technology (red, outer). You can’t get financing for a project that relies on prices in the far future. It could be worse than that, especially for demand side technologies, because technical gains get eaten up by rebound effects, which is what has happened to vehicle fuel economy in the last few decades. Furthermore, it’s hard to design a low-emissions economy in a low-price, high-emissions environment; R&D would be more productively pursued in an environment where the cost of emissions was visible (red, inner). It might be possible to mitigate the waste of resources by focusing on basic research, but that makes the delay between conception and application longer (green).

The net effect of the low-price strategy is that we’re likely to find ourselves in 2030 with a greater emissions commitment than we have today – more roads, McMansions, etc. – and no more will to reduce. We might have more options, but then again the options looked really good for energy efficiency in the 70s, and things aren’t much different today.There’s no way we’d be on track to hit 2C or 50% by 2050 or any other low-climate-impact goal. Sure, we might get lucky, and invent low-emissions energy supply technologies that are quickly deployable on a massive scale – but counting on that is not a robust strategy.

So, why is the technology-led strategy so persistent and popular, in spite of the fact that research and empty talk are often equated in the public mind? I think that one underlying mental model is, “the stone age didn’t end because we ran out of stones.” In other words, it only makes sense to abandon our high-emissions mode when the low-emissions alternative becomes intrinsically better in every respect. This is a strange standard – in effect, it says that there simply won’t be any solution to the public goods problem (negative environmental externalities) that doesn’t rely on strictly private benefits, without any intervention to internalize the externality. This is either an ultra-pessimistic view (people are too perverse to act to better their collective long-term interest) or an ultra-libertarian view (the loss of liberty from government action to internalize the externality is worse than the underlying problem).

The second mental model is the economist’s rational view of the world, i.e. that if people oppose emissions pricing, they must have perfectly good reasons, as in, “it would logically follow the only reasons for anyone to question a strategy based on increasing the costs of energy are complete ignorance and/or a crass willingness to destroy the planet for private gain.” The real situation isn’t that stark. In fact, there is very solid evidence that even technically sophisticated people don’t understand the accumulation dynamics of the climate, and that agency problems and externalities around emissions are widespread. Thus it isn’t really very surprising that locally, boundedly rational people oppose policies that would actually be in their best interest over the long haul.

So, what’s my alternative prescription? Pielke’s low emissions price is not a bad start, even though $5/TonCO2 or even $25/TonCO2 is basically a joke compared to the social cost of carbon at fair discount rates or what it takes to motivate behavior change. Apart from the direct benefits of doing this, it creates the infrastructure for higher prices in the future. We part ways on the details, I think. First, it’s crucial that we not advertise the investment of emissions revenue in R&D as a solution, because it’s not – it’s just a piece of the puzzle. Second, some of the money should go back to the public as rebates or tax and deficit reductions, because that will need to happen at higher prices. Third, there needs to be a credible commitment to higher prices in the future, to provide the incentive for deployment and private innovation over longer horizons. Fourth, to unlock innovation potential, old regulatory frameworks that hinder innovation, including environmental policies and building codes, need to be reformulated in more flexible ways; this should be popular even absent climate concerns. Fifth, markets need to be created or altered to solve the landlord-tenant problem and other institutional obstacles to deployment; the higher the carbon price, the more opportunity people will see in such changes. To the extent that we can’t do all of this now, we don’t sit on our hands and pretend, we build the basis for action in the future by improving mental models that currently constrain action. That doesn’t mean social engineering; it’s a process of making models and data accessible and transparent enough for people to discover that current policies don’t result in a good outcome along the dimensions that they value for various possible futures.

[Update – afterthought: where the low-emissions-price scenario might make a lot of sense is in small regions. Then, it would generate a useful revenue stream without causing enough pain to cause significant leakage of emissions out of the jurisdiction. It would probably be easier to keep the tech $ in-region in early stage R&D than it would be later, during deployment, when manufacturing would be susceptible to offshoring. Still, you’d have to think of it as a stepping stone, not a solution.]

2 thoughts on “Stop talking, start studying?”