The answer is evidently now “no”, but until recently the UofM’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research director Patrick Barkey thought so:

“As early as last summer we still thought Montana would escape this recession,” he said. “We knew the national economic climate was uncertain, but Montana had been doing pretty well in the previous two recessions. We now know this is a global recession, and it is a more severe recession, and it’s a recession that’s not going to leave Montana unscathed.”

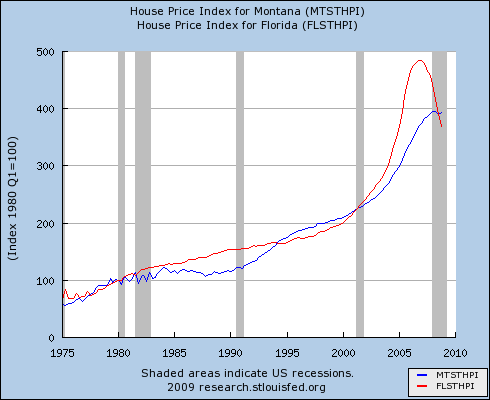

Indeed, things aren’t as bad here as they are in a lot of other places – yet. Compare our housing prices to Florida’s:

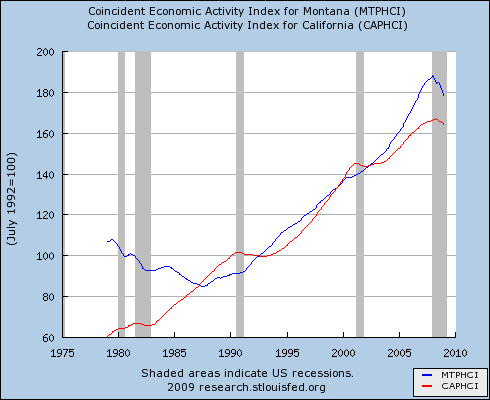

On the other hand, our overall economic situation shows a bigger hit than some places with hard-hit housing markets. Here’s the Fed’s coincident index vs. California:

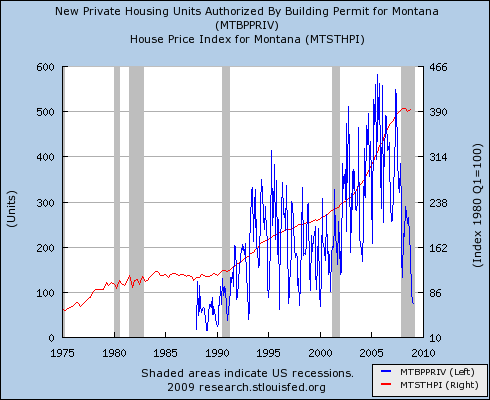

As one would expect, the construction and resource sectors are particularly hard hit by the double-whammy of housing bubble and commodity price collapse. In spite of home prices that seem to have held steady so far, new home construction has fallen dramatically:

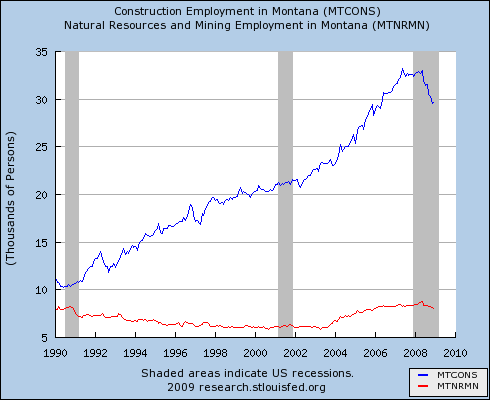

Interestingly, that hasn’t hit construction employment as hard as one would expect. Mining and resources employment has taken a similar hit, though you can hardly see it here because the industry is comparatively small (so why is its influence on MT politics comparatively large?).

So, where’s the bottom? For metro home prices nationwide, futures markets think it’s 10 to 20% below today, some time around the end of 2010. If the recession turns into a depression, that’s probably too rosy, and it’s hard to see how Montana could escape the contagion. But the impact will certainly vary regionally. The answer for Montana likely depends a lot on two factors: how bubbly was our housing market, and how recession-resistant is our mix of economic activity?

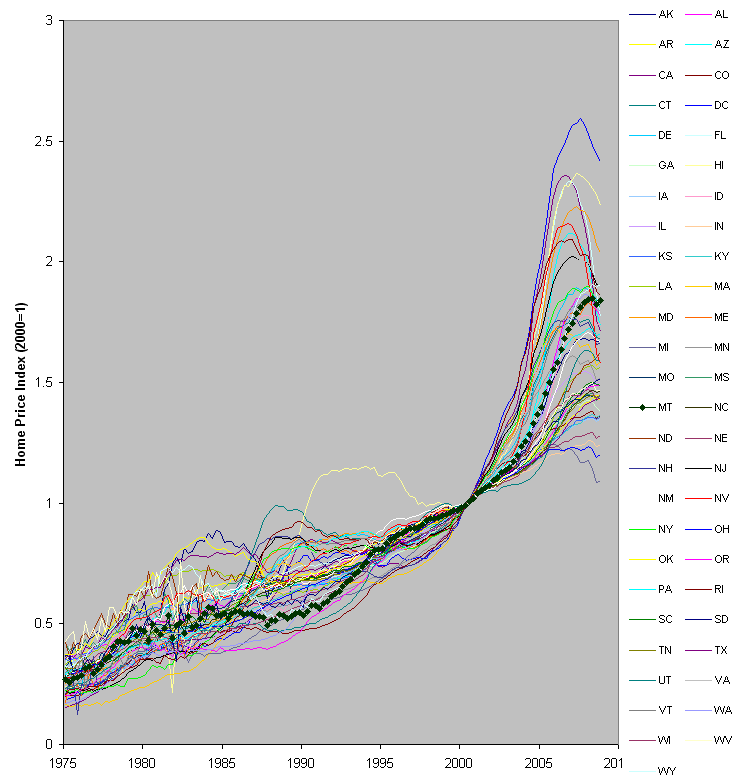

On the first point, here’s the Montana housing market (black diamonds), compared to the other 49 states and DC:

Prices above are normalized to 2000 levels, using the OFHEO index of conforming loan sales (which is not entirely representative – read on). At the end of 2003, Montana ranked 20th in appreciation from 2000. At the end of 2008, MT was 8th. Does the rise mean that we’re holding strong on fundamentals while others collapse? Or just that we’re a bunch of hicks, last to hear that the party’s over? Hard to say.

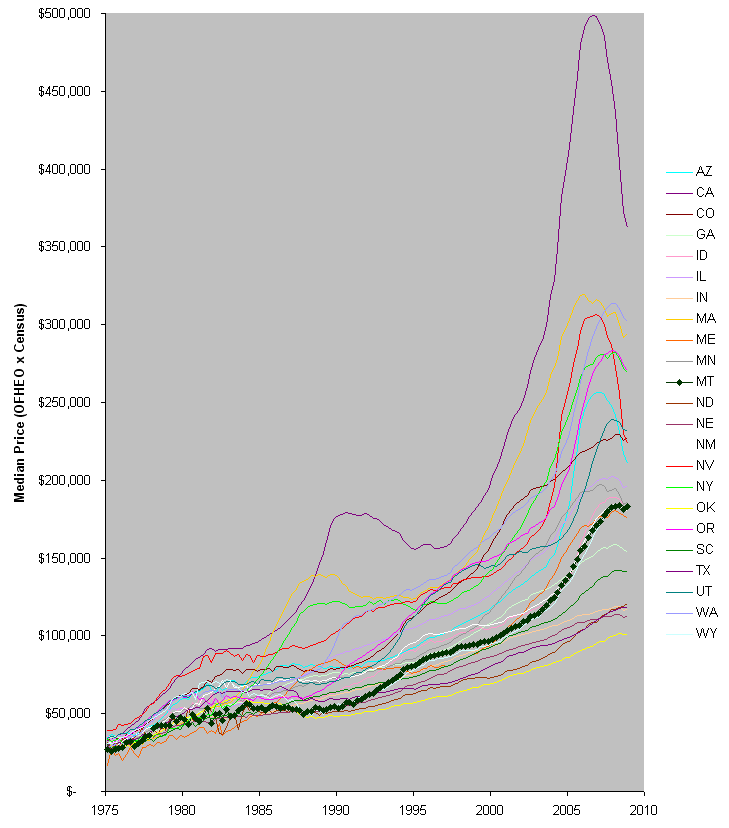

It’s perhaps a little easier to separate fundamentals from enthusiasm by looking at prices in absolute terms. Here, I’ve used the Census Bureau’s 2000 median home prices to translate the OFHEO index into $ terms:

Among its western region peers, a few other large states, and random states I like, Montana starts to look like a relative bargain still. The real question then is whether demographic trends (latte cowboys like me moving in) can buoy the market against an outgoing tide. I suspect that we’ll fare reasonably well in the long run, but suffer a significant undershoot in the near term.

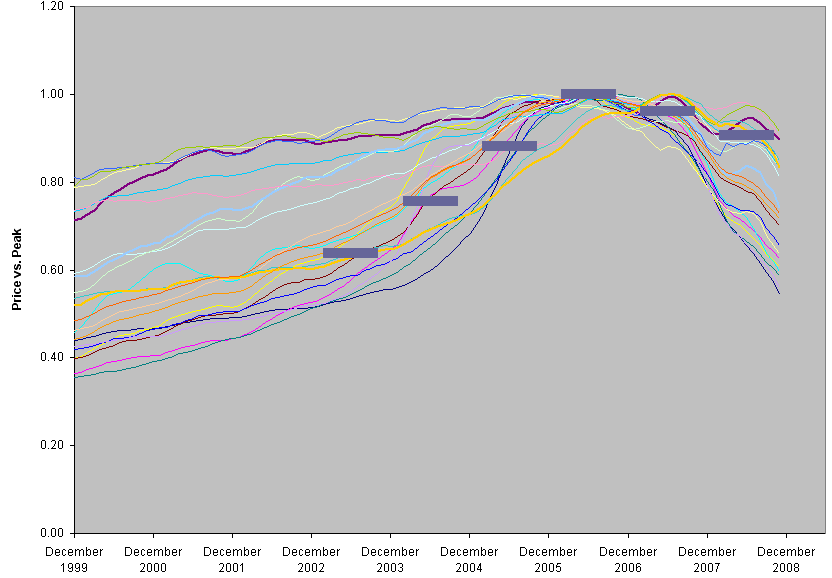

The OFHEO indices above are a little puzzling, in that so many states seem to be just now, or not yet, peaking. For comparison, here are the 20 metro areas in the CSI index (lines), together with Gallatin County’s median prices (bars):

These more representative indices still show Montana holding up comparatively well, but with Gallatin County peaking in 2006. I suspect that the OFHEO index is a biased picture of the wider market, due to its exclusion of nonconforming loans, and that this is a truer picture.