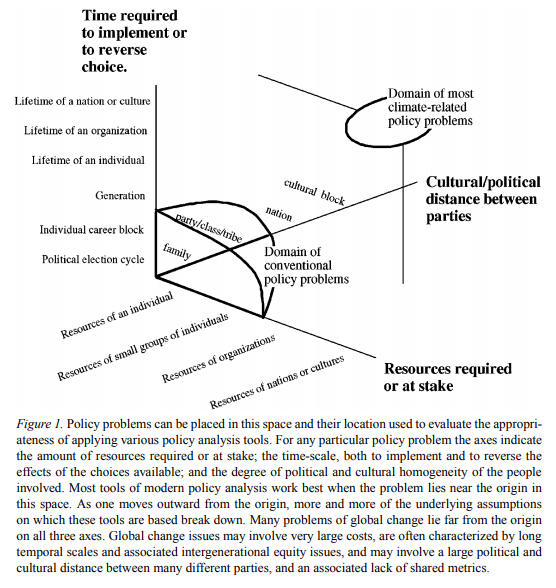

A while back I reviewed an interesting model of hormone interactions triggered by stress. The bottom line:

I think there might be a lot of interesting policy implications lurking in this model, waiting for an intrepid explorer with more subject matter expertise than I have. I think the crucial point here is that the structure identifies a mechanism by which patient outcomes can be strongly path dependent, where positive feedback preserves a bad state long after harmful stimuli are removed. Among other things, this might explain why it’s so hard to treat such patients. That in turn could be a basis for something I’ve observed in the health system – that a lot of doctors find autoimmune diseases mysterious and frustrating, and respond with a variation on the fundamental attribution error – attributing bad outcomes to patient motivation when delayed, nonlinear feedback is responsible.

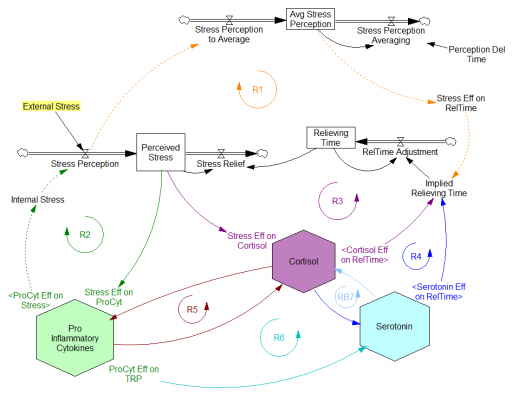

Since then, I’ve been reflecting on the fact that the internal positive feedbacks that give the hormonal system a tipping point, allowing people to get stuck in a bad state, are complemented and amplified by a set of external loops that do the same thing. I’ve reorganized my version of the model to show how this works:

Stress-Hormone Interactions (See also Fig. 1 in the original paper.)

The trigger for the system is External Stress (highlighted in yellow). A high average rate of stress perception lengthens the relieving time for stress. This creates a reinforcing loop, R1. This is analogous to the persistent pollution loop in World3, where a high level of pollution poisons the mechanisms that alleviate pollution.

I’ve constructed R1 with dashed arrows, because the effects are transient – when stress perception stops, eventually the stress effect on the relieving time returns to normal. (If I were reworking the model, I think I would simplify this effect, so that the stock of Perceived Stress affected the relieving time directly, rather than including a separate smooth, but this would not change the transience of the effect.)

A second effect of stress, mediated by Pro-inflammatory Cytokines, produces another reinforcing loop, R2. That loop does create Internal Stress, which makes it potentially self-sustaining. (Presumably that would be something like stress -> cytokines -> inflammation -> pain -> stress.) However, in simulations I’ve explored, a self-sustaining effect does not occur – evidently the Pro-inflammatory Cytokines sector does not contain a state that is permanently affected, absent an external stress trigger.

Still more effects of stress are mediated by the Cortisol and Serotonin sectors, and Cortisol-Pro-inflammatory Cytokines interactions. These create still more reinforcing loops, R3, R4, R5 and R6. Cortisol-serotonin affects appear to have multiple signs, making the net effect (RB67) ambiguous in polarity (at least without further digging into the details). Like R1 (the stress self-effect), R3, R4 and R6 operate by extending the time over which stress is relieved, which tends to increase the stock of stress. Even with long relief times, stress still drains away eventually, so these do not create permanent effects on stress.

However, within the Cortisol sector, there are persistent states that are affected by stress and inflammation. These are related to glucocorticoid receptor function, and they can be durably altered, making the effects of stress long term.

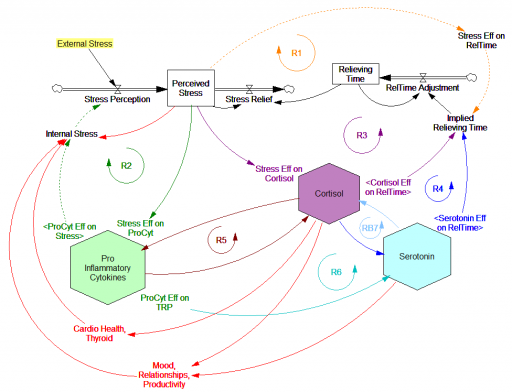

These dynamics alone make the system hard to understand and manage. However, I think the real situation is still more complex. Consider the following red links, which produce stress endogenously:

One possibility, discussed in the original paper but out of scope for the model, is that cognitive processing of stress has its own effects. For example, if stress produces stress, e.g., through worrying about stress, it could become self-sustaining. There are plenty of other possible mechanisms. The cortisol system affects cardiovascular health and thyroid function, which could lead to additional symptoms provoking stress. Similarly, mood affects family relationships and job productivity, which may contribute to stress.

These effects can be direct, for example if elevated cortisol causes stressful cardiovascular symptoms. But they could also be indirect, via other subsystems in one’s life. If you incur large health expenses or miss a lot of work, you’re likely to suffer financial stress. Presumably diet and exercise are also tightly coupled to this system.

All of these loops create abundant opportunity for tipping points that can lock you into good health or bad. I think they’re a key mechanism in poverty traps. Certainly they provide a clear mechanism that explains why mental health is not all in your head. Lack of appreciation for the complexity of this system may also explain why traditional medicine is not very successful in treating its symptoms.

If you’re on the bad side of a tipping point, all is not lost however. Positive loops that preserve a stressful state, acting as vicious cycles, can also operate in reverse as virtuous cycles, if a small improvement can be initiated. Even if it’s hard to influence physiology, there are other leverage points here that might be useful: changing your own approach to stress, engaging your relationships in the solution, and looking for ways to lower external stresses that keep the internal causes activated may all help.

I think I’m just scratching the surface here, so I’m interested in your thoughts.