I’m preparing for a talk on the dynamics of dictatorship or authoritarianism, which touches on many other topics, like polarization, conflict, terror and insurgency, and filter bubbles. I thought I’d share a few references, in the hope of attracting more. I’m primarily interested in mathematical models, or at least conceptual models that have clearly-articulated structure->behavior relationships. Continue reading “Dynamics of Dictatorship”

Month: August 2017

Ad Experiment

In the near future I’ll be running an experiment with serving advertisements on this site, starting with Google AdSense.

This is motivated by a little bit of greed (to defray the costs of hosting) and a lot of curiosity.

- What kind of ads will show up here?

- Will it change my perception of this blog?

- Will I feel any editorial pressure? (If so, the experiment ends.)

I’m generally wary of running society’s information system on a paid basis. (Recall the first deadly sin of complex system management.) On the other hand, there are certainly valid interests in sharing commercial information.

I plan to write about the outcome down the road, but first I’d like to get some firsthand experience.

What do you think?

Update: The experiment is over.

AI babble passes the Turing test

Here’s a nice example of how AI is killing us now. I won’t dignify this with a link, but I found it posted by a LinkedIn user.

I’d call this an example of artificial stupidity, not AI. The article starts off sounding plausible, but quickly degenerates into complete nonsense that’s either automatically generated or translated, with catastrophic results. But it was good enough to make it past someone’s cognitive filters.

For years, corporations have targeted on World Health Organization to indicate ads to and once to indicate the ads. AI permits marketers to, instead, specialize in what messages to indicate the audience, therefore, brands will produce powerful ads specific to the target market. With programmatic accounting for 67% of all international show ads in 2017, AI is required quite ever to make sure the inflated volume of ads doesn’t have an effect on the standard of ads.

One style of AI that’s showing important promise during this space is tongue process (NLP). informatics could be a psychological feature machine learning technology which will realize trends in behavior and traffic an equivalent method an individual’s brain will. mistreatment informatics during this method can match ads with people supported context, compared to only keywords within the past, thus considerably increasing click rates and conversions.

Meta MetaSD

I was looking at my google stats the other day, curious what posts interest people most. The answer was surprising. Guess what’s #1?

It’s not “Are Causal Loop Diagrams Useful?” (That’s #2.)

It’s not what I’d consider my best technical work, like Bathtub Statistics or Fun with 1D Vector Fields.

It’s not about something controversial, like On Limits to Growth or The alien hail Mary, and other climate policy plays.

Nor is it a hot topic, like Data science meets the bottom line.

It’s not something practical, like Writing an SD Conference Paper.

#1 is the Fibonacci sequence, How Many Pairs of Rabbits Are Created by One Pair in One Year?

Go figure.

Does statistics trump physics?

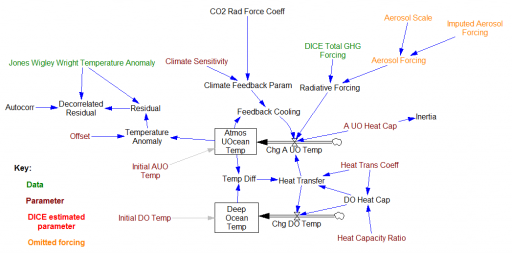

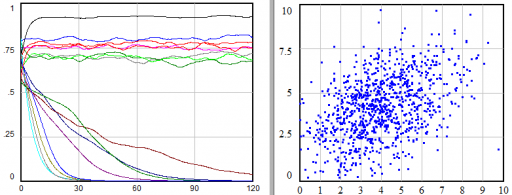

My dissertation was a critique and reconstruction of William Nordhaus’ DICE model for climate-economy policy (plus a look at a few other models). I discovered a lot of issues, for example that having a carbon cycle that didn’t conserve carbon led to a low bias in CO2 projections, especially in high-emissions scenarios.

There was one sector I didn’t critique: the climate itself. That’s because Nordhaus used an established model, from climatologists Schneider & Thompson (1981). It turns out that I missed something important: Nordhaus reestimated the parameters of the model from time series temperature and forcing data.

Nordhaus’ estimation focused on a parameter representing the thermal inertia of the atmosphere/surface ocean system. The resulting value was about 3x higher than Schneider & Thompson’s physically-based parameter choice. That delays the effects of GHG emissions by about 15 years. Since the interest rate in the model is about 5%, that lag substantially diminishes the social cost of carbon and the incentive for mitigation.

So … should an economist’s measurement of a property of the climate, from statistical methods, overrule a climatologist’s parameter choice, based on physics and direct observations of structure at other scales?

I think the answer could be yes, IF the statistics are strong and reconcilable with physics or the physics is weak and irreconcilable with observations. So, was that the case?

Weapons of Math Destruction

A nice TED talk explaining how algorithms can reinforce unfairness, inequity and errors of judgment:

Note the discussion of teacher value added modeling. This corresponds with what I found in my own assessment here.

ICE Roadkill

Several countries have now announced eventual bans of internal combustion engines. It’s nice that such a thing can now be contemplated, but this strikes me as a fundamentally flawed approach.

Banning a whole technology class outright is inefficient. When push comes to shove, that inefficiency is likely to lead to an implementation that’s complex and laden with exceptions. Bans and standards are better than nothing, but that regulatory complexity gives opponents something real to whine about. Then the loonies come out. At any plausible corporate cost of capital, a ban in 2040 has near-zero economic weight today.

Rather than banning gas and diesel vehicles at some abstract date in the far future, we should be pricing their externalities now. Air and water pollution, noise, resource extraction, the opportunity cost of space for roads and parking, and a dozen other free rides are good candidates. And, electric vehicles should not be immune to the same charges where applicable.

Once the basic price signal points the transportation market in the right direction, we can see what happens, and tinker around the edges with standards that address particular misperceptions and market failures.

A tale of Big Data and System Dynamics

I recently worked on a fascinating project that combined Big Data and System Dynamics (SD) to good effect. Neither method could have stood on its own, but the outcome really emphasized some of the strategic limitations of the data-driven approach. Including SD in the project simultaneously lowered the total cost of analysis, by avoiding data processing for things that could be determined a priori, and increased its value by connecting the data to business context.

I can’t give a direct account of what we did, because it’s proprietary, but here’s my best shot at the generalizable insights. The context was health care for some conditions that particularly affect low income and indigent populations. The patients are hard to track and hard to influence.

Two efforts worked in parallel: Big Data (led by another vendor) and System Dynamics (led by Ventana). I use the term “SD” loosely, because much of what we ultimately did was data-centric: agent based modeling and estimation of individual-level nonlinear dynamic models in Vensim. The Big Data vendor’s budget was two orders of magnitude greater than ours, mostly due to some expensive system integration tasks, but partly due to the caché of their brand and flashy approach, I suspect. Continue reading “A tale of Big Data and System Dynamics”

AI is killing us now

I’ve been watching the debate over AI with some amusement, as if it were some other planet at risk. The Musk-Zuckerberg kerfuffle is the latest installment. Ars Technica thinks they’re both wrong:

At this point, these debates are largely semantic.

I don’t see how anyone could live through the last few years and fail to notice that networking and automation have enabled an explosion of fake news, filter bubbles and other information pathologies. These are absolutely policy relevant, and smarter AI is poised to deliver more of what we need least. The problem is here now, not from some impending future singularity.

Ars gets one point sort of right:

Plus, computer scientists have demonstrated repeatedly that AI is no better than its datasets, and the datasets that humans produce are full of errors and biases. Whatever AI we produce will be as flawed and confused as humans are.

I don’t think the data is really the problem; it’s the assumptions the data’s treated with and the context in which that occurs that’s really problematic. In any case, automating flawed aspects of ourselves is not benign!

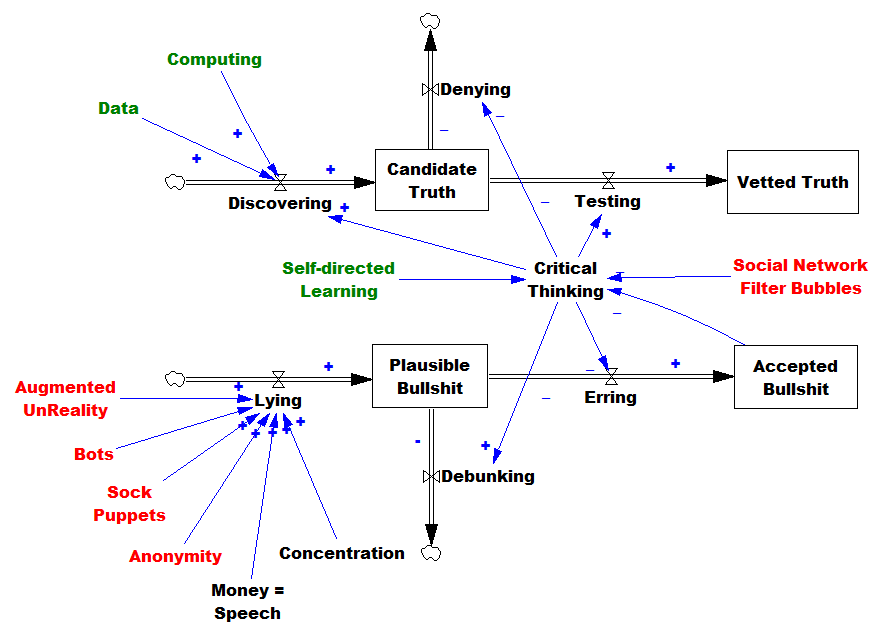

Here’s what I think is going on:

AI, and more generally computing and networks are doing some good things. More data and computing power accelerate the discovery of truth. But truth is still elusive and expensive. On the other hand, AI is making bullsh!t really cheap (pardon the technical jargon). There are many mechanisms by which this occurs:

- CGI and digital editing make it possible to fake anything (“augmented unreality” above).

- Bots that can pass the crude Turing test of social media streams produce disinformation far faster than humans can.

- Sockpuppet automation platforms assist bad actors at disinforming.

- Anonymity limits the effectiveness of reputation.

- Social networks make it easy for people to coalesce into tribes, rejecting information that might disconfirm their biases.

These amplifiers of disinformation serve increasingly concentrated wealth and power elites that are isolated from their negative consequences, and benefit from fueling the process. We wind up wallowing in a sea of information pollution (the deadliest among the sins of managing complex systems).

As BS becomes more prevalent, various reinforcing mechanisms start kicking in. Accepted falsehoods erode critical thinking abilities, and promote the rejection of ideas like empiricism that were the foundation of the Enlightenment. The proliferation of BS requires more debunking, taking time away from discovery. A general erosion of trust makes it harder to solve problems, opening the door for opportunistic rent-seeking non-solutions.

I think it’s a matter of survival for us to do better at critical thinking, so we can shift the balance between truth and BS. That might be one area where AI could safely assist. We have other assets as well, like the explosion of online learning opportunities. But I think we also need some cultural solutions, like better management of trust and anonymity, brakes on concentration, sanctions for lying, rewards for prediction, and more time for reflection.

The survival value of wrong beliefs

… reasons for the survival of antiscientific views. It’s basically a matter of evolution. When crazy ideas negatively affect survival, they die out. But evolutionary forces are vastly diminished under some conditions, or even point the wrong way …

NPR has an alarming piece on school science.

She tells her students — like Nick Gurol, whose middle-schoolers believe the Earth is flat — that, as hard as they try, science teachers aren’t likely to change a student’s misconceptions just by correcting them. Gurol says his students got the idea of a flat planet from basketball star Kyrie Irving, who said as much on a podcast.

“And immediately I start to panic. How have I failed these kids so badly they think the Earth is flat just because a basketball player says it?” He says he tried reasoning with the students and showed them a video. Nothing worked.

“They think that I’m part of this larger conspiracy of being a round-Earther. That’s definitely hard for me because it feels like science isn’t real to them.”

For cases like this, Yoon suggests teachers give students the tools to think like a scientist. Teach them to gather evidence, check sources, deduce, hypothesize and synthesize results. Hopefully, then, they will come to the truth on their own.

This called to mind a post from way back, in which I considered reasons for the survival of antiscientific views.

It’s basically a matter of evolution. When crazy ideas negatively affect survival, they die out. But evolutionary forces are vastly diminished under some conditions, or even point the wrong way:

- Non-experimental science (reliance on observations of natural experiments; no controls or randomized assignment)

- Infrequent replication (few examples within the experience of an individual or community)

- High noise (more specifically, low signal-to-noise ratio)

- Complexity (nonlinearity, integrations or long delays between cause and effect, multiple agents, emergent phenomena)

- “Unsalience” (you can’t touch, taste, see, hear, or smell the variables in question)

- Cost (there’s some social or economic penalty imposed by the policy implications of the theory)

- Commons (the risk of being wrong accrues to society more than the individual)

These are, incidentally, some of the same circumstances that make medical trials difficult, such that most papers are false.

Consider the flat earth idea. What cost accrues to students who hold this belief? None whatsoever, I think. A flat earth model will make terrible predictions of all kinds of things, but students are not making or relying on such predictions. The roundness of the earth is obviously not salient. So really, the only survival value that matters to students is the benefit of tribal allegiance.

If there are intertemporal dynamics, the situation is even worse. For any resource or capability investment problem, there’s worse before better behavior. Recovering depleted fish stocks requires diminished effort, and less to eat, in the near term. If a correct belief implies good long run stock management, adherents of the incorrect belief will have an advantage in the short run. You can’t count on selection weeding out the “dumb tribes” for planetary-scale problems, because we’re all in one.

This seems like a pretty intractable problem. If there’s a way out, it has to be cultural. If there were a bit more recognition of the value on making correct predictions, the halo of that would spill over to diminish the attractiveness of silly theories. That’s a case that ought to be compelling for basketball fans. Who wants to play on a team that can’t predict what the opponents will do, or how the ball will bounce?