To avoid quarantining students, a school district tries moving them around every 15 minutes.

Oh no.

To reduce the number of students sent home to quarantine after exposure to the coronavirus, the Billings Public Schools, the largest school district in Montana, came up with an idea that has public health experts shaking their heads: Reshuffling students in the classroom four times an hour.

The strategy is based on the definition of a “close contact” requiring quarantine — being within 6 feet of an infected person for 15 minutes or more. If the students are moved around within that time, the thinking goes, no one will have had “close contact” and be required to stay home if a classmate tests positive.

For this to work, there would have to be a nonlinearity in the dynamics of transmission. For example, if the expected number of infections from 2 students interacting with an infected person for 10 minutes each were less than the number from one student interacting with an infected person for 20 minutes, there might be some benefit. This would be similar to a threshold in a dose-response curve. Unfortunately, there’s no evidence for such an effect – if anything, increasing the number of contacts by fragmentation makes things worse.

Scientific reasoning has little to do with the real motivation:

Greg Upham, the superintendent of the 16,500-student school district, said in an interview that contact tracing had become a huge burden for the district, and administrators were looking for a way to ease the burden when they came up with the movement idea. It was not intended to “game the system,” he said, but rather to encourage the staff to be cognizant of the 15-minute window.

Regardless of the intent, this is absolutely an example of gaming the system. However, you game rules, but you can’t fool mother nature. The 15-minute window is a decision rule for prioritizing contact tracing, invented in the context of normal social mixing. Administrators have confused it with a physical phenomenon. Whether or not they intended to game the system, they’re likely to get what they want: less contact tracing. This makes the policy doubly disastrous: it increases transmission, and it diminishes the preventive effects of contact tracing and quarantine. In short order, that means more infections. A few doublings of cases will quickly overwhelm any reduction in contact tracing burden from shuffling students around.

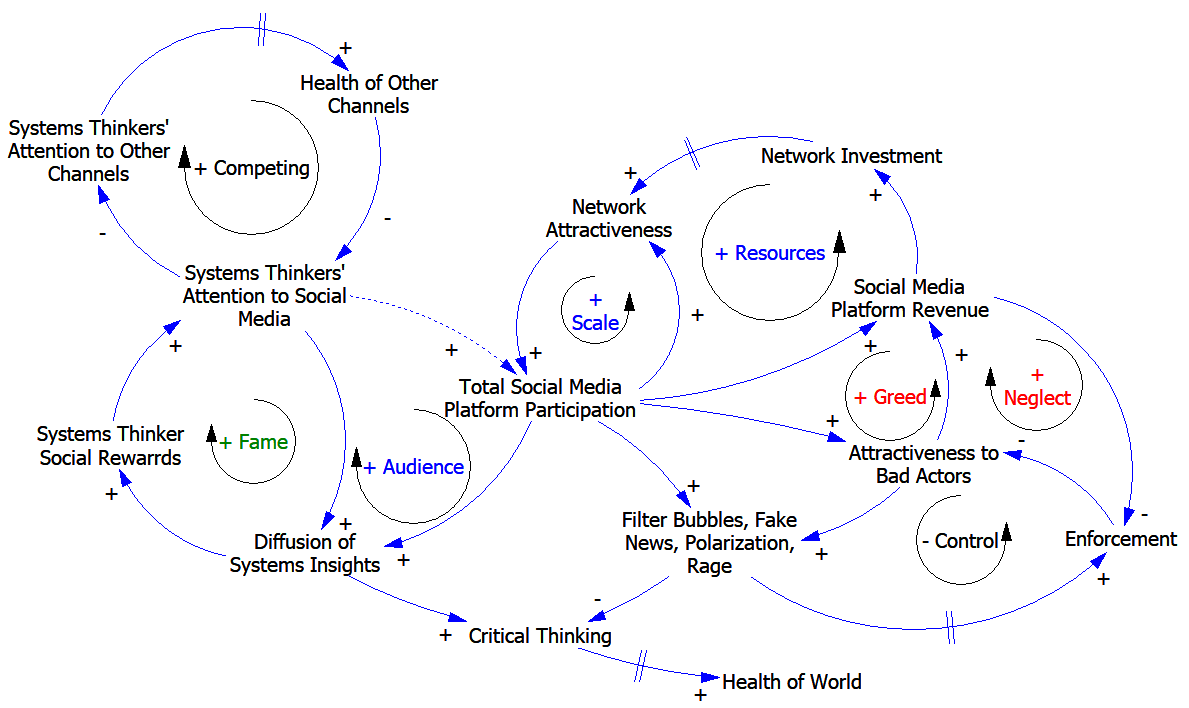

I think the administrators who came up with this might want to consider adding systems thinking to the curriculum.