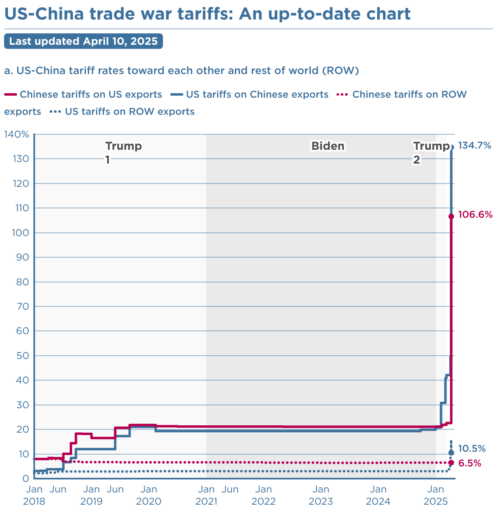

I think this will be the reference mode for the escalation archetype for years to come:

It’s not necessarily true that what goes up must come down. Have we reached tariff orbital escape velocity? Or will the positive loops driving this reverse from vicious to virtuous cycle without some intervening catastrophe?