Surfing a bit, it looks like the furor over the leaked Danish text actually has at least four major components:

- Lack of per capita convergence in 2050.

- Requirement that the upper tier of developing countries set targets.

- Institutional arrangements that determine control of funds and activity.

- The global peak in 2020 and decline to 2050.

These are evident in coverage in Politico and COP15.dk, for example.

I’ve already tackled #1, which is an illusion based on flawed analysis. I also commented on #2 – whether you set formal targets or not, absolute emissions need to fall in every major region if atmospheric GHG concentrations and radiative imbalance are to stabilize or decline. I don’t have an opinion on #3. #4 is what I’d like to talk about here.

There seem to be two responses to #4: dissatisfaction with the very idea of peaking and declining on anything like that schedule, and dissatisfaction with the burden sharing at the peak.

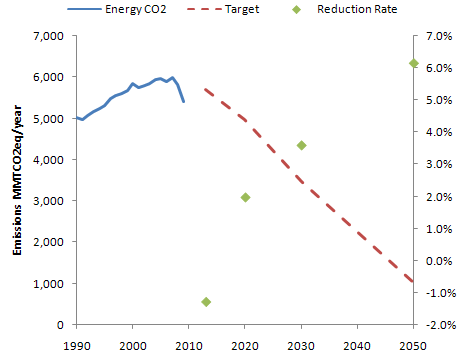

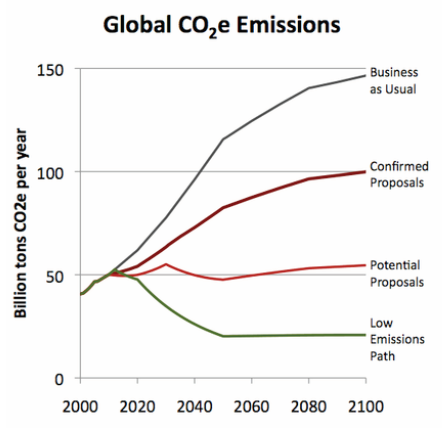

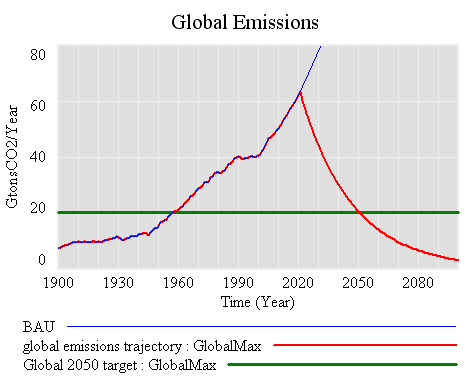

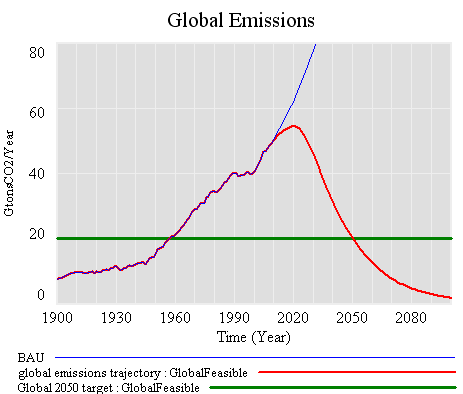

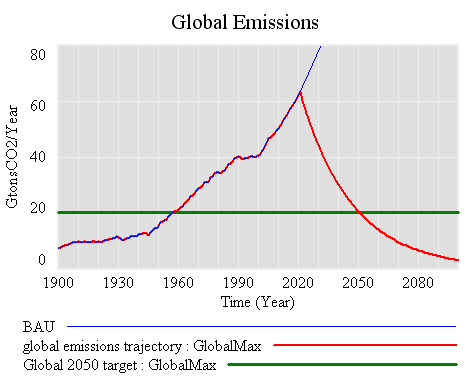

First, the global trajectory. There are a variety of possible emissions paths that satisfy the criteria in the Danish text. Here’s one (again relying on C-ROADS data and projections, close to A1FI in the future):

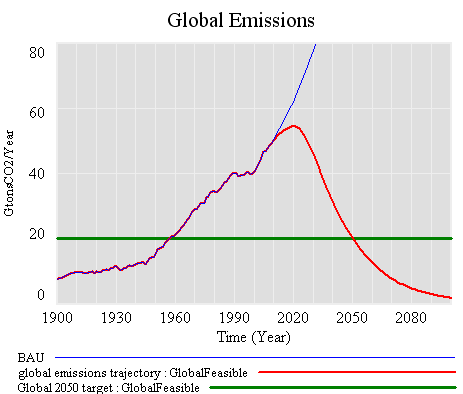

Here, emissions grow along Business-As-Usual (BAU), peak in 2020, then decline at 3.75%/year to hit the 2050 target. This is, of course, a silly trajectory, because its basically impossible to turn the economy on a dime like this, transitioning overnight from growth to decline. More plausible trajectories have to be smooth, like this:

One consequence of the smoothness constraint is that emissions reductions have to be faster later, to make up for the growth that occurs during a gradual transition from growing to declining emissions. Here, they approach -5%/year, vs. -3.5% in the “pointy” trajectory. A similar constraint arises from the need to maintain the area under the emissions curve if you want to achieve similar climate outcomes.

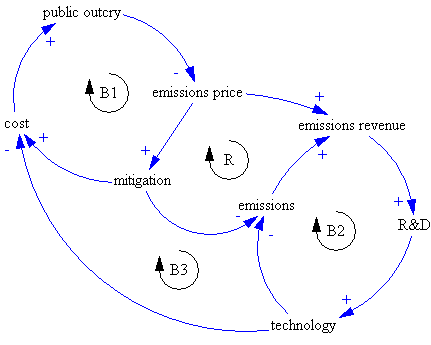

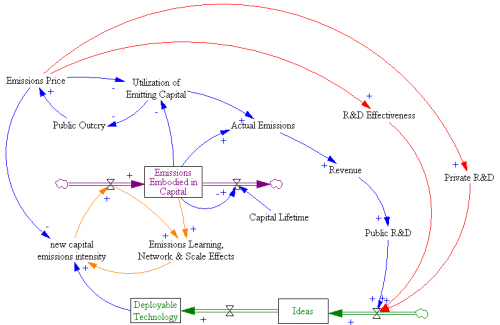

So, anyone who argues for a later peak is in effect arguing for (a) faster reductions later, or (b) weaker ambitions for the climate outcome. I don’t see how either of these is in the best interest of developing countries (or developed, for that matter). (A) means spending at most an extra decade building carbon-intensive capital, only to abandon it at a rapid rate a decade or two later. That’s not development. (B) means more climate damages and other negative externalities, for which growth is unlikely to compensate, and to which the developing countries are probably most vulnerable.

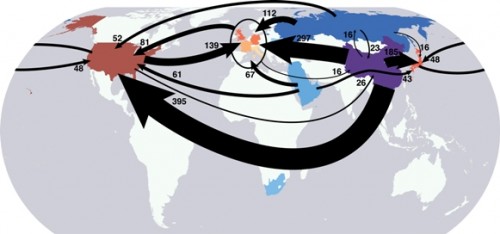

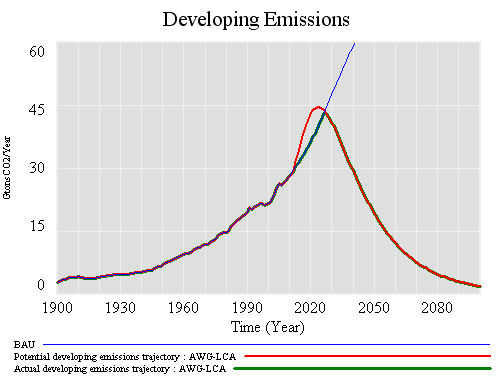

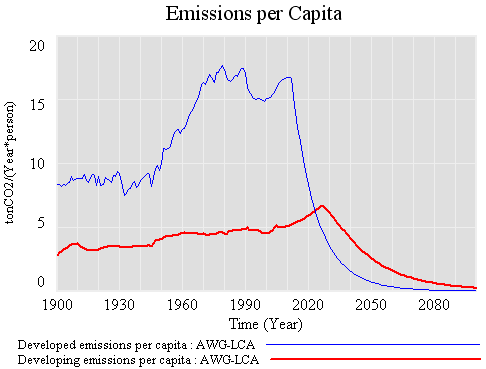

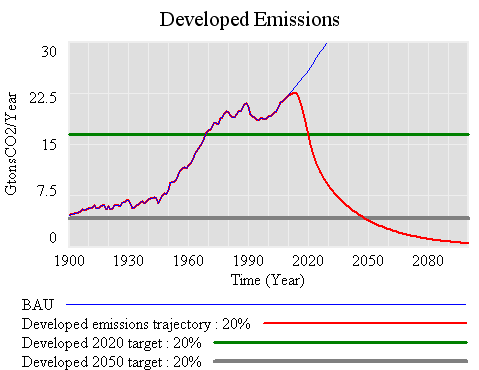

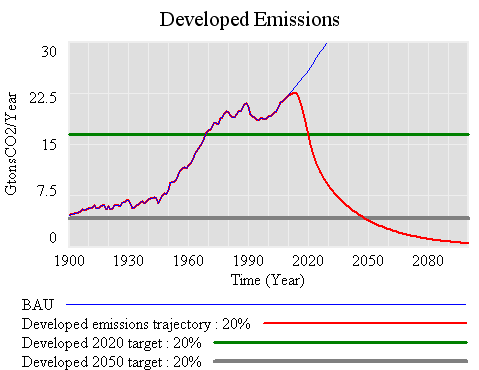

If, for sake of argument, we take my smooth version of the Danish text target as a given, there’s still the question of how emissions between now and 2050 are partitioned. If the developed world shoots for 20% below 1990 by 2020, the trajectory might look like this:

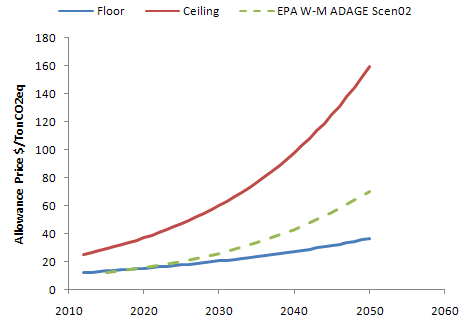

That’s a target that most would consider to be modest, yet to hit it, emissions have to peak by 2012, and decline at up to 8% per year through 2020. It would be easier to achieve in some regions, like the EU, that are already not far from Kyoto levels, but tough for the developed world as a whole. The natural turnover of buildings, infrastructure and power plants is 2 to 4%/year, so emissions declining at 8% per year means some combination of massive retrofits, where possible, and abandonment of carbon-emitting assets. If that were happening in the developed world, in tandem with free trade, rapid growth and no targets in the developing world, it would surely mean massive job dislocations. I expect that would cause the emission control regime in the developed world to crumble.

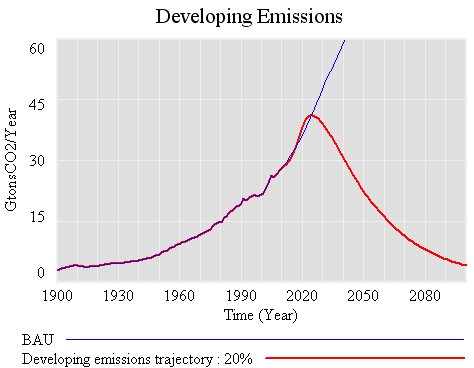

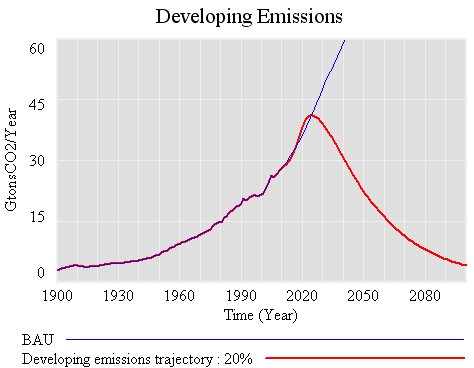

The -20% in 2020 trajectory creates surprisingly little headroom for growth in the developing world. Emissions can grow only until 2025 (vs. 2020 globally, and 2012 in the developing countries). Thereafter they have to fall at roughly the global rate.

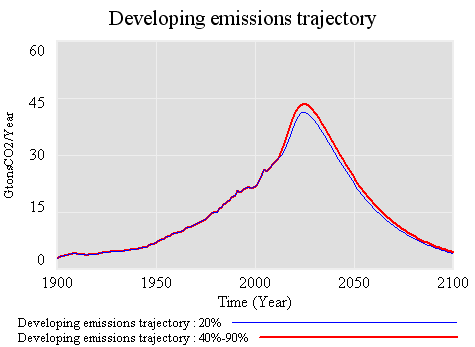

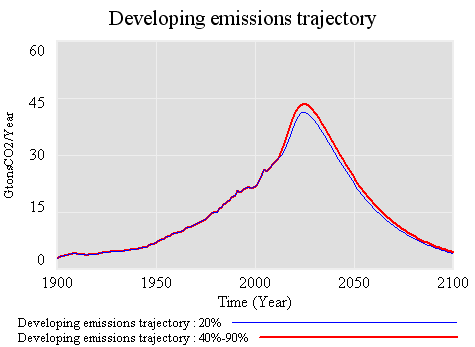

What if the developed world manages to go even faster, achieving -40% from 1990 by 2020, and -90% by 2050? Surprisingly, that buys the developing countries almost nothing. Emissions can rise a little higher, but must peak around the same time, and decline at the same rate. Some of the rise is potentially inaccessible, because it exceeds BAU, and no one really knows how to control economic growth.

The reason for this behavior is fairly simple: as soon as developed countries make substantial cuts of any size, they become bit players in the global emissions game. Further reductions, acting on a small basis, are very tiny compared to the large basis of developing country emissions. Thus the past is a story of high developed country cumulative emissions, but the future is really about the developing countries’ path. If developing countries want to push the emissions envelope, they have to accept that they are taking a riskier climate future, no matter what the developed world does. In addition, deeper cuts on the part of the developed world become very expensive, because marginal costs grow with the depth of the cut. On the whole everyone would be better off if the developing countries asked for more money rather than deeper emissions cuts in the developed world.

There’s a deeper reason to think that calls for deeper cuts in the developed world, to provide headroom for greater emissions growth in developing countries, are counterproductive. I think the mental model behind such calls is a mixture of the following:

- carbon fuels GDP, and GDP equals happiness

- developing countries have an urgent need to build certain critical infrastructure, after which they can reduce emissions

- slow growth fuels discontent, leading to revolution

- growth pays for pollution reductions (the Kuznets curve)

Certainly each of these ideas contains some truth, and each has played a role in the phenomenal growth of the developed world. However, each is also fallacious in important ways. The elements in (1) are certainly correlated, but the relationship between carbon and happiness is mediated by all kinds of institutional and social factors. The key question for (2) is, what kind of infrastructure? Cheap carbon invites building exactly the kind of infrastructure that the developed world is now locked into, and struggling to dismantle. (3) might be true, but I suspect that it has as more to do with inequitable distribution of wealth and power than it does with absolute wealth. Rapid growth can easily increase inequity. The empirical basis of the Kuznets curve in (4) is rather shaky. Attempts to grow out of the negative side effects of growth are essentially a pyramid scheme. Moreover, to the extent that growth is successful, preferences shift to nonmarket amenities like health and clean air, so the cost of the negatives of growth grows.

Rather than following the developed countries down a blind alley, the developing countries could take this opportunity to bypass our unsustainable development path. By implementing emissions controls now, they could start building a low-carbon-friendly infrastructure, and get locked into sustainable technologies, that won’t have to be dismantled or abandoned in a few decades. This would mean developing institutions that internalize environmental externalities and allocate property rights sensibly. As a byproduct, that would help the poorest within their countries avoid the consequences of the new wealth of their elites. Preferences would evolve toward low-carbon lifestyles, rather than shopping, driving, and conspicuous consumption. Now, if we could just figure out how to implement the same insights here in the developed world …