XKCD:

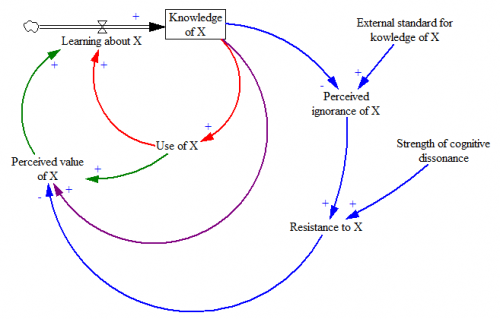

Here’s my quick take on the feedback structure behind this:

Knowledge of X (with X = algebra, cooking, …) is at the heart of a nest of positive feedback loops that make learning about X subject to vicious or virtuous cycles.

Knowledge of X (with X = algebra, cooking, …) is at the heart of a nest of positive feedback loops that make learning about X subject to vicious or virtuous cycles.

- The more you know about X, the more you find opportunities to use it, and vice versa. If you don’t know calculus, you tend to self-select out of engineering careers, thus fulfilling the “I’ll never use it” prophecy. Through use, you learn by doing, and gain further knowledge.

- Similarly, the more use you get out of X, the more you perceive it as valuable, and the more motivated you are to learn about it.

- When you know more, you also may develop intrinsic interest or pride of craft in the topic.

- When you confront some external standard for knowledge, and find yourself falling short, cognitive dissonance can kick in. Rather than thinking, “I really ought to up my game a bit,” you think, “algebra is for dorks, and those pointy-headed scientists are just trying to seize power over us working stiffs.”

I’m sure this could be improved on, for example by recognizing that attitudes are a stock.

Still, it’s easy to see here how algebra education goes wrong. In school, the red and green loops are weak, because there’s typically no motivating application more compelling than a word problem. Instead, there’s a lot of reliance on external standards (grades and testing), which encourages resistance.

A possible remedy therefore is to drive education with real-world projects, so that algebra emerges as a tool with an obvious need, emphasizing the red and green loops over the blue. An interesting real-world project might be self-examination of the role of the blue loop in our lives.