It seems that we Americans are engaged in an arms race with our own government. Bozeman is the latest to join in, with its recent acquisition of an armored vehicle:

Arms races are an instance of the escalation archetype, where generally the only winning strategy is not to play, but it’s particularly foolish to run an arms race against ourselves.

Arms races are an instance of the escalation archetype, where generally the only winning strategy is not to play, but it’s particularly foolish to run an arms race against ourselves.

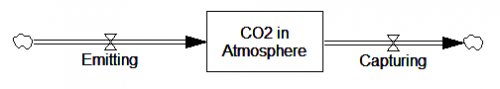

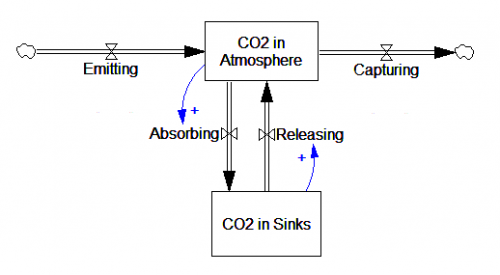

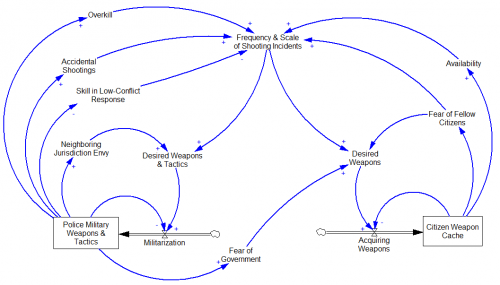

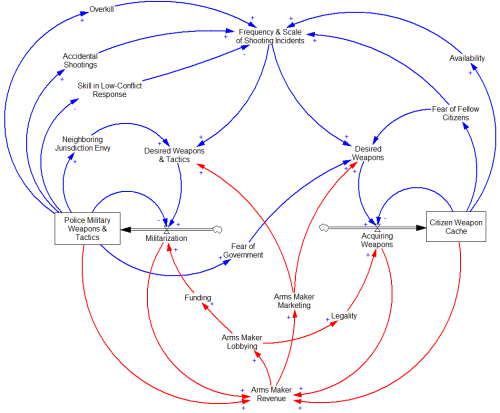

Here’s how it works:

The police (left) and citizens (right) each have stocks of weapons and associated skills and attitudes. Each “side” adjusts those stocks toward a desired level, which is set by various signals.

Citizens, for example, see media coverage of school shootings and less spectacular events, and arm themselves against their fellow citizens and against the eventuality of totalitarian government. A side effect of this is that, as the general availability of weapons increases, the frequency and scale of violent conflict increases, all else equal. This in itself reinforces the citizen perception of the need to arm.

The government (i.e. the police) respond to the escalation of violent conflict in their own locally rational way as well. They acquire heavy weapons and train tactical teams. But this has a number of side effects that further escalate conflict. Spending and training on paramilitary approaches necessarily comes at the expense of non-violent policing methods.

… Lester said he’s concerned about the potential overuse of such commanding vehicles among some police departments, a common criticism in the wake of the Ferguson protests.“When you bring that to the scene,” he said, “you bring an attitude that’s not necessarily needed.”

Accidents happen, and the mere availability of heavy armor encourages overkill, as we saw in Ferguson. And police departments are not immune to keeping up with the Joneses:

“For a community our size, we’re one of the last communities that does not have an armored rescue vehicle,” he said.

This structure is a nest of reinforcing feedback loops – I haven’t labeled them, because every loop above is positive, except the two inner loops in the acquisition/militarization stock control processes.

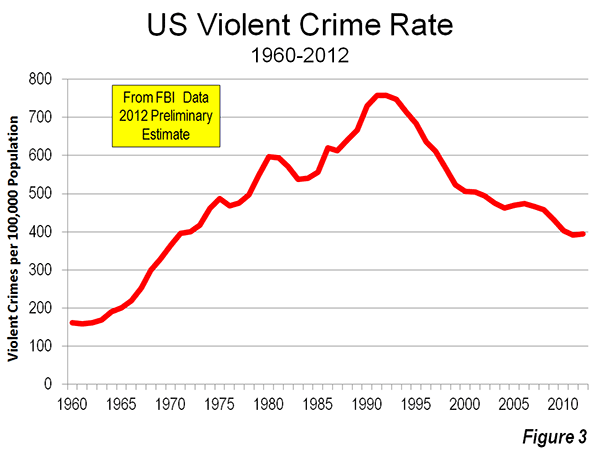

Strangely, this is happening at a time in which violent crime rates are trending down. This means that the driver of escalation must be more about perceptions and fear of potential harm than about actual shooting incidents.

Carrying the escalation to its conclusion, one of two things has to happen. The police win, and we have a totalitarian state. Or, the citizens win, and we have stateless anarchy. Neither outcome is really a “win.”

The alternative is to reverse the escalation, and make the reinforcing loops virtuous rather than vicious cycles. This is harder than it should be, because there’s a third party involved, that profits from escalation (red):

Arms makers generate revenue from weapon sales and service, and reinvest that in marketing, to increase both parties desired weapons, and in lobbying to preserve the legality of assault weapons and fund the grant programs that enable small towns to have free armor.

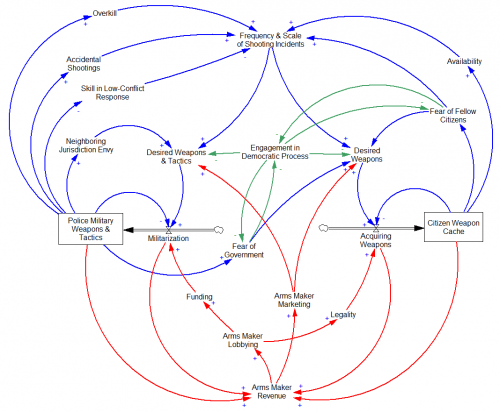

Fortunately, there is a remedy. Voters can (at least indirectly) fire the Bozeman officials who “forgot” to run the armored vehicle acquisition through any public process, and defund the Homeland (In)Security programs that bring heavy weapons to our doorsteps.

The difficult pill to swallow is that, for this to work, citizens have to de-escalate too. Reinstating the assault weapons ban is messy, and perhaps ineffective given the large stock of weapons now widely distributed. Maybe the first change should be cultural: recognizing that arming oneself to the teeth is a fear-driven antisocial response to our situation, and that ballots are a better solution than bullets.