The US Copyright office has issued its latest opinion on AI and copyright:

https://natlawreview.com/article/copyright-offices-latest-guidance-ai-and-copyrightability

The U.S. Copyright Office’s January 2025 report on AI and copyrightability reaffirms the longstanding principle that copyright protection is reserved for works of human authorship. Outputs created entirely by generative artificial intelligence (AI), with no human creative input, are not eligible for copyright protection. The Office offers a framework for assessing human authorship for works involving AI, outlining three scenarios: (1) using AI as an assistive tool rather than a replacement for human creativity, (2) incorporating human-created elements into AI-generated output, and (3) creatively arranging or modifying AI-generated elements.

The office’s approach to use of models seems fairly reasonable to me.

I’m not so enthusiastic about the de facto policy for ingestion of copyrighted material for training models, which courts have ruled to be fair use.

https://www.arl.org/blog/training-generative-ai-models-on-copyrighted-works-is-fair-use/

On the question of whether ingesting copyrighted works to train LLMs is fair use, LCA points to the history of courts applying the US Copyright Act to AI. For instance, under the precedent established in Authors Guild v. HathiTrust and upheld in Authors Guild v. Google, the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit held that mass digitization of a large volume of in-copyright books in order to distill and reveal new information about the books was a fair use. While these cases did not concern generative AI, they did involve machine learning. The courts now hearing the pending challenges to ingestion for training generative AI models are perfectly capable of applying these precedents to the cases before them.

I get that there are benefits to inclusive data for LLMs,

Why are scholars and librarians so invested in protecting the precedent that training AI LLMs on copyright-protected works is a transformative fair use? Rachael G. Samberg, Timothy Vollmer, and Samantha Teremi (of UC Berkeley Library) recently wrote that maintaining the continued treatment of training AI models as fair use is “essential to protecting research,” including non-generative, nonprofit educational research methodologies like text and data mining (TDM). …

What bothers me is that allegedly “generative” AI is only accidentally so. I think a better term in many cases might be “regurgitative.” An LLM is really just a big function with a zillion parameters, trained to minimize prediction error on sentence tokens. It may learn some underlying, even unobserved, patterns in the training corpus, but for any unique feature it may essentially be compressing information rather than transforming it in some way. That’s still useful – after all, there are only so many ways to write a python script to suck tab-delimited text into a dataframe – but it doesn’t seem like such a model deserves much IP protection.

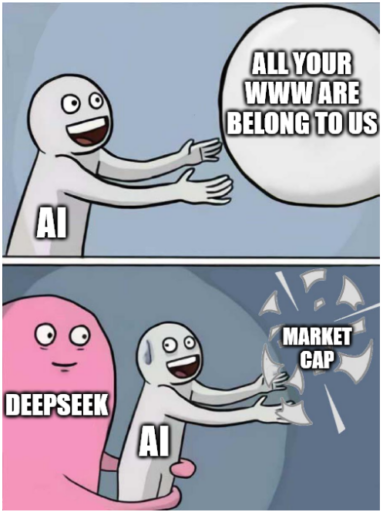

Perhaps the solution is laissez faire – DeepSeek “steals” the corpus the AI corps “transformed” from everyone else, commencing a race to the bottom in which the key tech winds up being cheap and hard to monopolize. That doesn’t seem like a very satisfying policy outcome though.