I’m just back from two weeks camping in the desert. Ironically, we had a lot of rain. Apart from the annoyance of cooking in the rain, water in the desert is a wonderful sight.

We spent one night in transit at Las Vegas Bay campground on Lake Mead. We were surprised to discover that it’s not a bay anymore – it’s a wash. The lake has been declining for a decade and is now 100 feet below its maximum.

It turned out that this is not unprecedented – it happened in 1965, for example. After that relatively brief drought, it took a decade to claw back to “normal” levels.

The recent decline looks different to me, though – it’s not a surprising, abrupt decline, it’s a long, slow ramp, suggesting a persistent supply-demand imbalance. Bizarrely, it’s easy to get lake level data, but hard to find a coherent set of basin flow measurements. Would you invest in a company with a dwindling balance sheet, if they couldn’t provide you with an income statement?

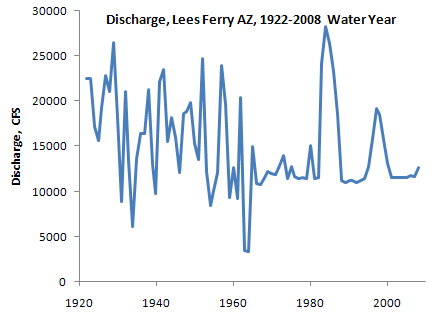

It appears to me that the Colorado River system is simply overallocated, and their hasn’t been any feedback between reality (actual water availability) and policy (water use, governed by the Law of the River). It also appears that the problem is not with the inflow to Lake Mead. Here’s discharge past the Lees Ferry guage, which accounts for the bulk of the lake’s supply:

Notice that the post-2000 flows are low (probably reflecting mainly the statutory required discharge from Glenn Canyon dam upstream), but hardly unprecedented. My hypothesis is that the de facto policy for managing water levels is to wait for good years to restore the excess withdrawals of bad years, and that demand management measures in the interim are toothless. That worked back when river flows were not fully subscribed. The trouble is, supply isn’t stationary, and there’s no reason to assume that it will return to levels that prevailed in the early years of river compacts. At the same time, demand isn’t stationary either, as population growth in the west drives it up. To avoid Lake Mead drying up, the system is going to have to get a spine, i.e. there’s going to have to be some feedback between water availability and demand.

I’m sure there’s a much deeper understanding of water dynamics among various managers of the Colorado basin than I’ve presented here. But if there is, they’re certainly not sharing it very effectively, because it’s hard for an informed tinkerer like me to get the big picture. Colorado basin managers should heed Krys Stave’s advice:

Water managers increasingly are faced with the challenge of building public or stakeholder support for resource management strategies. Building support requires raising stakeholder awareness of resource problems and understanding about the consequences of different policy options.