Ever since the housing market fell apart, I’ve been meaning to write about some excellent work on federal financial guarantee programs, by colleagues Jim Hines (of TUI fame) and Jim Thompson.

Designing Programs that Work.

This document is part of a series reporting on a study of tederal financial guarantee programs. The study is concerned with how to design future guarantee programs so that they will be more robust, less prone to problems. Our focus has been on internal (that is. endogenous) weaknesses that might inadvertently be designed into new programs. Such weaknesses may be described in terms of causal loops. Consequently, the study is concerned with (a) identifying the causal loops that can give rise to problematic behavior patterns over time, and (b) considering how those loops might be better controlled.

Their research dates back to 1993, when I was a naive first-year PhD student, but it’s not a bit dated. Rather, it’s prescient. It considers a series of design issues that arise with the creation of government-backed entities (GBEs). From today’s perspective, many of the features identified were the seeds of the current crisis. Jim^2 identify a number of structural innovations that control the undesirable behaviors of the system. It’s evident that many of these were not implemented, and from what I can see won’t be this time around either.

There’s a sophisticated model beneath all of this work, but the presentation is a nice example of a nontechnical narrative. The story, in text and pictures, is compelling because the modeling provided internal consistency and insights that would not have been available through debate or navel rumination alone.

I don’t have time to comment too deeply, so I’ll just provide some juicy excerpts, and you can read the report for details:

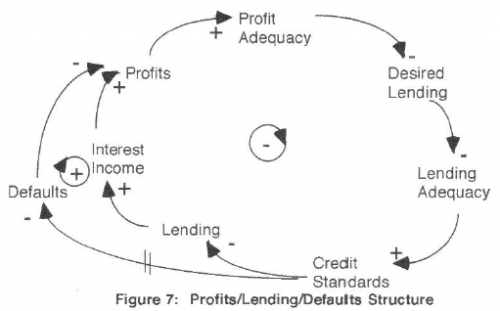

The profit-lending-default spiral

The situation described here is one in which an intended corrective process is weakened or reversed by an unintended self-reinforcing process. The corrective process is one in which inadequate profits are corrected by rising income on an increasing portfolio. The unintended self-reinforcing process is one in which inadequate profits are met with reduced credit standards which cause higher defaults and a further deterioration in profits. Because the fee and interest income lrom a loan begins to be received immediately, it may appear at first that the corrective process dominates, even if the self-reinforcing is actually dominant. Managers or regulators initially may be encouraged by the results of credit loosening and portfolio building, only to be surprised later by a rising tide of bad news.

As is typical, some well-intentioned policies that could mitigate the problem behavior have unpleasant side-effects. For example, adding risk-based premiums for guarantees worsens the short-term pressure on profits when standards erode, creating a positive loop that could further drive erosion.

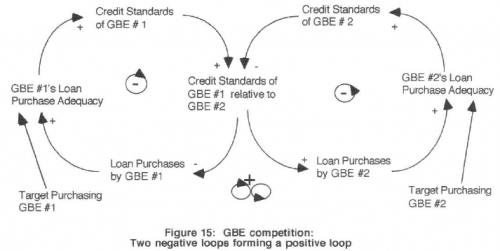

GBE competition

lf there are two or more GBEs in a single market, they may compete against each other for a larger share of loan purchases. Among the ways a GBE may compete tor loans is by trying to become a more attractive partner lo originators. Being more attractive may translate into accepting loans of lower credit standards – or accepting less rigorously documented loans, which in practice probably means lower credit standards, too. It should be clear that something analogous to an arms race may result. Each GBE may continually try tor an advantage that is continually wiped out by the response of the other GBE. The result of this process may be steadily declining credit standards of GBEs.

Extrapolative expectations

Extrapolative expectations and the closely related positive loop involved in speculative bubbles have been discussed by social scientists for at least a century and a half. The basic idea is that if potential buyers interpret a price rise as part of a continuing trend, they may be drawn into the market by their expectation of continuing price rises,2e thereby swelling demand and causing prices to continue rising.

Most discussions emphasize the destabilizing or deviation-amplifying potential of the positive loops in which extrapolative expectations play a key part. However it is important to realize first that not all positive feedback is destabilizing, and second, that extrapolative expectations in different sectors can have different effects. In the present context, extrapolative expectations operate in two different kinds of sectors: First in the consumer sector – that is, among people who are thinking of purchasing the underlying asset – and second, in the financing sector.

In the consumer sector, a potential buyer may believe that prices will be higher in the future, if prices have been rising recently. Hence, he will believe that he will pay more if he waits and that he might make money if he buys now. Further if the buyer must finance his purchase he will be comforted by a belief that he can sell the asset to pay off the loan if some misfortune befalls him. These considerations increase an individuals willingness to buy now. A greater willingness to buy, spread over the whole population, will mean an increase in demand and thus a continued increase in prices.

In the financing sectors, a perception that prices will continue to trend upwards makes managers of financial institutions more comfortable with lower credit standards. They feel more certain that they can get their money out, if the lender defaults. Further. because loans do not default immediately when made, financial managers may tend to evaluate standards — particularly standards involving the value of collateral – in terms of the future. For example, the loan-to-value ratio on a loan might not meet the target now, but, if prices continue to rise, the ratio might be better than target at, say, three years in the future. As a consequence, the currently acceptable loan to value ratio might be pegged higher than the target standard. (Note: a higher loan-to-value ratio is less credit worthy). People will find that they can get the financing they previously were denied. Demand will increase and prices will continue to rise.

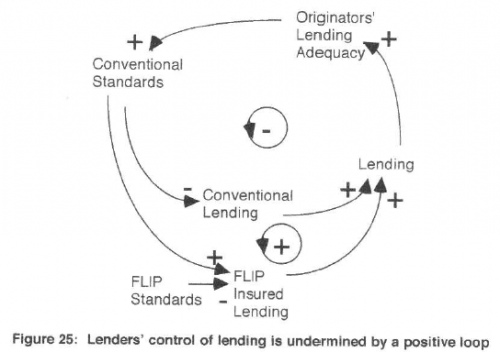

Federal Loan Insurance Program Expansion

… the attempt to control lending adequacy creates an intended negative loop and an unintended positive loop. The negative loop controls lending adequacy by adjusting standards. The positive loop weakens or even reverses the negative loop. … The problem here is that conventional standards can move in one direction while FLIP credit standards remain unchanged or even move in the other direction.

What I find particularly interesting about this work is the richness provided by the detailed knowledge of the industry that was embodied in the model. The press is full of talk about bubbly expectations and moral hazard these days, but generally short on explanation of the mechanisms. This report really gets into an operational description of the (potentially perverse) ways lenders, consumers, regulators, the Fed, and guarantee programs interact. That sheds light on many behaviors that are not widely recognized, shows why piecemeal solutions will fail, and identifies systemic solutions that will work.

There are some additional chapters to the report that I’ll comment on in a future installment. Further information on the modeling is available from the authors on request.

Apologies for any typos I missed – the report excerpts are from a scan. Thanks to Jim Thompson for providing the material.