The ongoing bailout/stimulus debate is decidedly Keynesian. Yet Keynes was a halfhearted Keynesian:

US Keynesianism, however, came to mean something different. It was applied to a fiscal revolution, licensing deficit finance to pull the economy out of depression. From the US budget of 1938, this challenged the idea of always balancing the budget, by stressing the need to boost effective demand by stimulating consumption.

None of this was close to what Keynes had said in his General Theory. His emphasis was on investment as the motor of the economy; but influential US Keynesians airily dismissed this as a peculiarity of Keynes. Likewise, his efforts to separate capital projects from ordinary budgets, balanced if possible, found few echoes in Washington, despite frequent mention of his name.

Should this surprise us? It does not appear to have disconcerted Keynes. ‘Practical men were often the slaves of some defunct economist,’ he wrote. By the end of the second world war, Lord Keynes of Tilton was no mere academic scribbler but a policymaker, in a debate dominated by second-hand versions of ideas he had put into circulation in a previous life. He was enough of a pragmatist, and opportunist, not to quibble. After dining with a group of Keynesian economists in Washington, in 1944, Keynes commented: ‘I was the only non-Keynesian there.’

FT.com, In the long run we are all dependent on Keynes

This got me wondering about the theoretical underpinnings of the stimulus prescription. Economists are talking in the language of the IS/LM model, marginal propensity to consume, multipliers for taxes vs. spending, and so forth. But these are all equilibrium shorthand for dynamic concepts. Surely the talk is founded on dynamic models that close loops between money, expectations and the real economy, and contain an operational representation of money creation and lending?

The trouble is, after a bit of sniffing around, I’m not seeing those models. On the jacket of Dynamic Macroeconomics, James Tobin wrote in 1997:

“Macrodynamics is a venerable and important tradition, which fifty or sixty years ago engaged the best minds of the economics profession: among them Frisch, Tinbergan, Harrod, Hicks, Samuelson, Goodwin. Recently it has been in danger of being swallowed up by rational expectations, moving equilibrium, and dynamic optimization. We can be grateful to the authors of this book for keeping alive the older tradition, while modernizing it in the light of recent developments in techniques of dynamic modeling.”

’”James Tobin, Sterling Professor of Economics Emeritus, Yale University

Is dynamic macroeconomics still moribund, supplanted by CGE models (irrelevant to the problem at hand) and black box econometric methods? Someone please point me to the stochastic behavioral disequilibrium nonlinear dynamic macroeconomics literature I’ve missed, so I can sleep tonight knowing that policy is informed by something more than comparative statics.

In the meantime, the most relevant models I’m aware of are in system dynamics, not economics. An interesting option (which you can read and run) is Nathan Forrester’s thesis, A Dynamic Synthesis of Basic Macroeconomic Theory (1982).

Forrester’s model combines Samuelson’s multiplier accelerator, Metzler’s inventory-adjustment model, Hicks’ IS/LM, and the aggregate-supply/aggregate-demand model into a 10th order continuous dynamic model. The model generates an endogenous business cycle (4-year period) as well as a longer (24-year) cycle. The business cycle arises from inventory and employment adjustment, while the long cycle involves multiplier-accelerator and capital stock adjustment mechanisms, involving final demand. Forrester used the model to test a variety of countercyclic economic policies, commonly recommended as antidotes for business cycle swings:

Results of the policy tests explain the apparent discrepancy between policy conclusions based on static and dynamic models. The static results are confirmed by the fact that countercyclic demand-management policies do stabilize the demand-driven [long] cycle. The dynamic results are confirmed by the fact that the same countercyclic policies destabilize the business cycle. (pg. 9)

It’s not clear to me what exactly this kind of counterintuitive behavior might imply for our current situation, but it seems like a bad time to inadvertently destabilize the business cycle through misapplication of simpler models.

It’s unclear to what extent the model applies to our current situation, because it doesn’t include budget constraints for agents, and thus doesn’t include explicit money and debt stocks. While there are reasonable justifications for omitting those features for “normal” conditions, I suspect that since the origin of our current troubles is a debt binge, those justifications don’t apply where we are now in the economy’s state space. If so, then the equilibrium conclusions of the IS/LM model and other simple constructs are even more likely to be wrong.

I presume that the feedback structure needed to get your arms around the problem properly is in Jay Forrester’s System Dynamics National Model, but unfortunately it’s not available for experimentation.

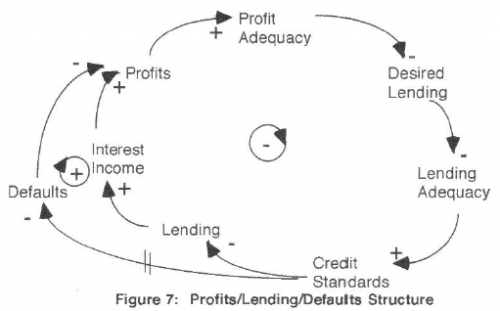

John Sterman’s model of The Energy Transition and the Economy (1981) does have money stocks and debt for households and other sectors. It doesn’t have an operational representation of bank reserves, and it monetizes the deficit, but if one were to repurpose the model a bit (by eliminating the depletion issue, among other things) it might provide an interesting compromise between the two Forrester models above.

I still have a hard time believing that macroeconomics hasn’t trodden some of this fertile ground since the 80s, so I hope someone can comment with a more informed perspective. However, until someone disabuses me of the notion, I have the gnawing suspicion that the models are broken and we’re flying blind. Sure hope there aren’t any mountains in this fog.