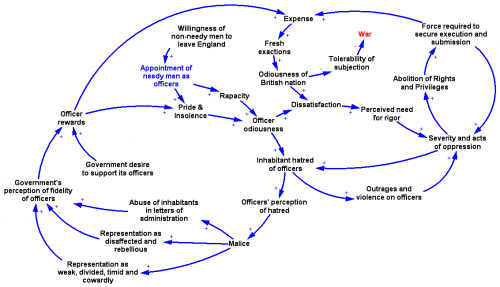

I ran across a nice interpretation of Paul Krugman’s comments on China’s monetary policy. It’s also a great example of the limitations of verbal descriptions of complex feedbacks:

In order to invest in China you need state permission and the state limits how much money comes in. It essentially has an import quota on Yuan.

This means that while Yuan are loose in the international market and therefore cheap, they are actually tight at home and therefore expensive. Because China is controlling the flow on money across the border it can have a loose international monetary policy but a tight domestic monetary policy.

Indeed, it goes deeper than that. A loose international Yuan bids up foreign demand for Chinese goods. This in turn both increase the quantity of goods China produces and their domestic price. Essentially, foreign consumers are given a price advantage relative to domestic consumers.

However, China doesn’t want domestic consumers to face higher prices. So, it has to tighten the domestic Yuan even tighter. It has too push down domestic demand so that the sum of international demand plus domestic demand are not so high that they produce domestic inflation.

The tight domestic Yuan, therefore, is driving down Chinese consumption at precisely the time in which the world could use more consumption. The loose international Yuan also gives foreigners a price advantage when buying Chinese goods and so it is driving down inflation in the US at precisely the time the Fed is trying to dive it up.

However, the story still gets worse from there – I am really riffing here, half of this is just occurring to me as I type. The loose international Yuan can only be used to produce manufactured goods. Manufacturing requires commodities both as the feed stock for the actual goods and to be used in the construction of new manufacturing facilities.

What does that mean. It should mean that when the Fed loosens policy, that China responds by loosening the International Yuan which in turn gets shunted towards commodities. Thus rather than boosting the consumer price level as we hope, Fed easing actually winds up boosting commodities.

This is because China is offsetting the total increase in worldwide consumer demand by tightening the Yuan at home, and boosting the total increase in commodity demand by loosening the Yuan abroad.

If this is a bit baffling, it helps to get the context from the originals. Still, it begs for a model or at least a diagram. At least the punch line is simple:

Thus this Yuan policy does all the wrong things.

Meanwhile, in a bizarre parallel universe where climate policy exists in a vacuum, China calls the US a preening pig. Couldn’t they at least wait for Palin to be elected? Seriously, US climate policy is a joke, but Chinese monetary-industrial policy is just as destructive.