I don’t know if Thor Heyerdahl had Polynesian origins or Rapa Nui right, but he did nail the stovepiping of thinking in organizations:

“And there’s another thing,” I went on.

“Yes,” said he. “Your way of approaching the problem. They’re specialists, the whole lot of them, and they don’t believe in a method of work which cuts into every field of science from botany to archaeology. They limit their own scope in order to be able to dig in the depths with more concentration for details. Modern research demands that every special branch shall dig in its own hole. It’s not usual for anyone to sort out what comes up out of the holes and try to put it all together.

…

Carl was right. But to solve the problems of the Pacific without throwing light on them from all sides was, it seemed to me, like doing a puzzle and only using the pieces of one color.

Thor Heyerdahl, Kon-Tiki

This reminds me of a few of my consulting experiences, in which large firms’ departments jealously guarded their data, making global understanding or optimization impossible.

This is also common in public policy domains. There’s typically an abundance of micro research that doesn’t add up to much, because no one has bothered to build the corresponding macro theory, or to target the micro work at the questions you need to answer to build an integrative model.

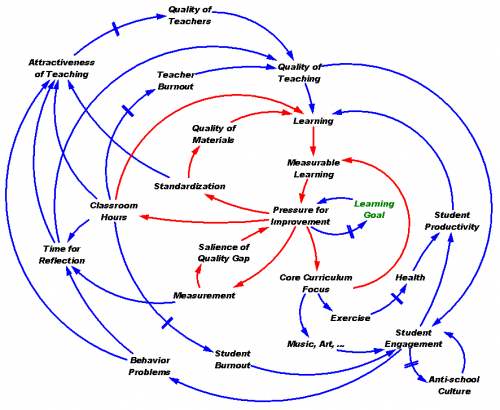

An example: I’ve been working on STEM workforce issues – for DOE five years ago, and lately for another agency. There are a few integrated models of workforce dynamics – we built several, the BHEF has one, and I’ve heard of efforts at several aerospace firms and agencies like NIH and NASA. But the vast majority of education research we’ve been able to find is either macro correlation studies (not much causal theory, hard to operationalize for decision making) or micro examination of a zillion factors, some of which must really matter, but in a piecemeal approach that makes them impossible to integrate.

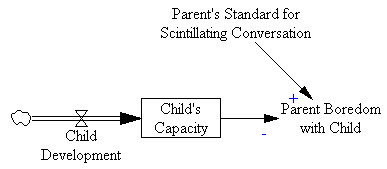

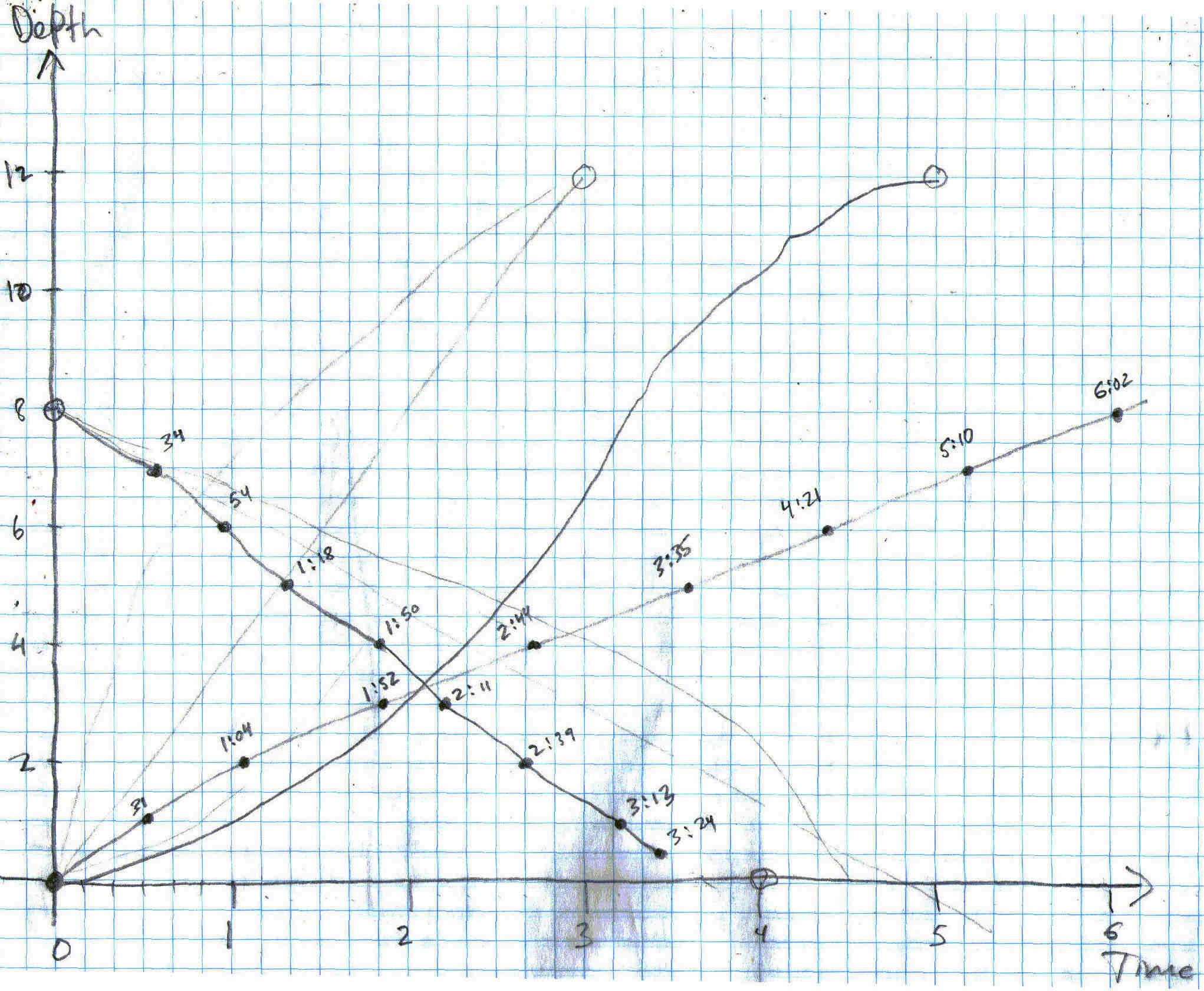

An integrated model needs three things: what, how, and why. The “what” is the state of the system – stocks of students, workers, teachers, etc. in each part of the system. Typically this is readily available – Census, NSF and AAAS do a good job of curating such data. The “how” is the flows that change the state. There’s not as much data on this, but at least there’s good tracking of graduation rates in various fields, and the flows actually integrate to the stocks. Outside the educational system, it’s tough to understand the matrix of flows among fields and economic sectors, and surprisingly difficult even to get decent measurements of attrition from a single organization’s personnel records. The glaring omission is the “why” – the decision points that govern the aggregate flows. Why do kids drop out of science? What attracts engineers to government service, or the finance sector, or leads them to retire at a given age? I’m sure there are lots of researchers who know a lot about these questions in small spheres, but there’s almost nothing about the “why” questions that’s usable in an integrated model.

I think the current situation is a result of practicality rather than a fundamental philosophical preference for analysis over synthesis. It’s just easier to create, fund and execute standalone micro research than it is to build integrated models.

The bad news is that vast amounts of detailed knowledge goes to waste because it can’t be put into a framework that supports better decisions. The good news is that, for people who are inclined to tackle big problems with integrated models, there’s lots of material to work with and a high return to answering the key questions in a way that informs policy.