A new paper by Stechemesser et al. in Science evaluates the large suite of climate policies in

Editor’s summary

It is easy for countries to say they will reduce their emissions of greenhouse gases, but these statements do not mean that the policies they adopt will be effective. Stechemesser et al. evaluated 1500 climate policies that have been implemented over the past 25 years and identified the 63 most successful ones. Some of those successes involved rarely studied policies and unappreciated combinations. This work illustrates the kinds of policy efforts that are needed to close the emissions gaps in various economic sectors. —Jesse SmithAbstract

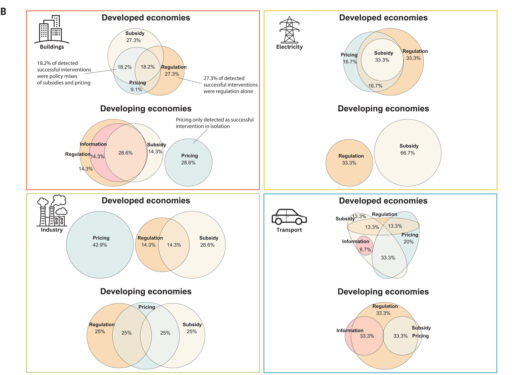

Meeting the Paris Agreement’s climate targets necessitates better knowledge about which climate policies work in reducing emissions at the necessary scale. We provide a global, systematic ex post evaluation to identify policy combinations that have led to large emission reductions out of 1500 climate policies implemented between 1998 and 2022 across 41 countries from six continents. Our approach integrates a comprehensive climate policy database with a machine learning–based extension of the common difference-in-differences approach. We identified 63 successful policy interventions with total emission reductions between 0.6 billion and 1.8 billion metric tonnes CO2. Our insights on effective but rarely studied policy combinations highlight the important role of price-based instruments in well-designed policy mixes and the policy efforts necessary for closing the emissions gap.

Effective policies from Stechemesser et al.

Effective policies from Stechemesser et al.

Emil Dimanchev has a useful critique on the platform formerly known as Twitter. I think there are two key points. First, the method may have a hard time capturing gradual changes. This is basically a bathtub statistics problem: policies are implemented as step changes, but the effect may involve one or more integrations (from implementation lags, slow capital turnover, R&D pipeline delays, etc.). The structural problem is probably exacerbated by a high level of noise. The bottom line is that some real effects may not be readily detectable.

ED’s second key point is essentially a variant of “correlation is not causation”:

To understand effectiveness of a policy (or of a policy mix), we are interested in the probability (P) that it reduces emissions (our hypothesis, H) when implemented (our condition, E). In statistics, we denote that P(H|E). But the authors do something very different.

Instead, the authors take all cases (arbitrarily) defined as effective (E) and then estimate how often a policy was implemented around that time. That’s P(E|H). The two shouldn’t be conflated (though Tversky and Kahneman showed people often make that mistake).

An example of this conflation is when people conclude from the paper that a policy mix needs CO2 pricing to be effective. But the data merely show that in most of their historical emission breaks, pricing was part of the policy mix, a statement of P(E|H).

Concluding from the paper that pricing increases the probability of a break in emissions, or P(H|E), is exactly like saying that you should play a musical instrument to increase your chances of winning a Nobel prize because most Nobel laureates play a musical instrument.

I have mixed feelings about this argument. It’s correct in principle, but I think it’s incomplete, because there are strong mechanistic arguments for the effectiveness of some climate policies, that should complement the probabilistic reasoning here. I think getting to this mechanistic view is actually what ED drives at in his prescription:

An empirical investigation of effectiveness would involve looking at all cases an instrument or a mix was implemented, and estimating the CO2 reductions it caused while controlling for all confounding variables. That’s obviously very hard. Again, that’s not what the paper does.

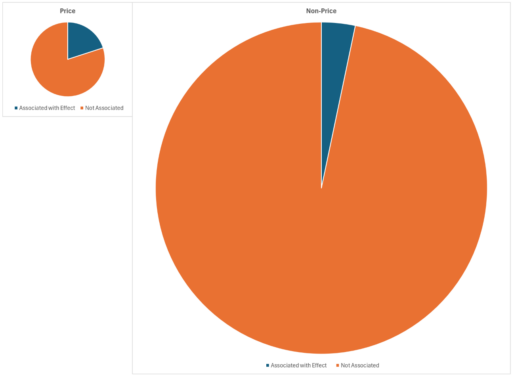

To me, this means use an a priori energy model to detect policy effects, rather than an abstract ML method. When the IEA climate policy database first came out, I thought that would be a really cool project. Then I thought about how much work it would be, so that will have to wait for another time. But given the abundance of mechanistic arguments favoring some policies, I can’t help leaning towards the view that “correlation is not causation – but it’s a good start”. Here’s a suggestive view of the results, stratifying the price and non-price initiatives, with the pies roughly sized by absolute numbers of policies:

Lets suppose, in the worst case, that the effects observed in Stechemesser et al. are simply random luck. Why should the non-price policies be associated with effects so much less frequently? The paper may be weak evidence, but I think it’s not inconsistent with the idea – backed by models – that a lot of climate and energy policies are seriously flawed (CAFE standards and Energy Star come to mind) or simply fluffy feel-good greenwash.

Lets suppose, in the worst case, that the effects observed in Stechemesser et al. are simply random luck. Why should the non-price policies be associated with effects so much less frequently? The paper may be weak evidence, but I think it’s not inconsistent with the idea – backed by models – that a lot of climate and energy policies are seriously flawed (CAFE standards and Energy Star come to mind) or simply fluffy feel-good greenwash.