I was at the doctor’s office for a routine checkup recently – except that it’s not a checkup anymore, it’s a “wellness visit”. Just to underscore that, there’s a sign on the front door, stating that you can’t talk to the doctor about any illnesses. So basically you can’t talk to your doctor if you’re sick. Let the insanity of that sink in. Why? Probably because an actual illness would take more time than your insurance would pay for. It’s not just my doc – I’ve seen this kind of thing in several offices.

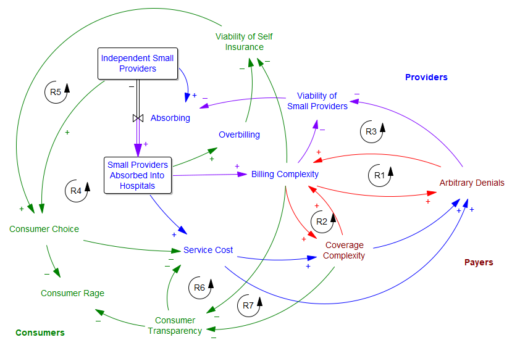

To my eyes, US health care is getting worse, and its pathologies are much more noticeable. I think consolidation is a big part of the problem. In many places, the effective number of competing firms on both the provider side is 1 or 2, and the number of payers is 2 or 3. I roughly sketched out the effects of this as follows:

The central problem is that the few payers and providers left are in a war of escalation with each other. I suspected that it started with the payers’ systematic denial of, or underpayment for, procedure claims. The providers respond by increasing the complexity of their billing, so they can extract every penny. This creates loops R1 and R2.

Then there’s a side effect: as billing complexity and arbitrary denials increase, small providers lack the economies of scale to fight the payer bureaucracy; eventually they have to fold and accept a buyout from a hospital network (R3). The payers have now shot themselves in the foot, because they’re up against a bigger adversary.

But the payers also benefit from this complexity, because transparency becomes so bad that consumers can no longer tell what they’re paying for, and are more likely to overpay for insurance and copays (R7). This too comes with a cost for the payers though, because consumers no longer contribute to cost control (R6).

As this goes on, consumers no longer have choices, because self-insuring becomes infeasible (R5) – there’s nowhere to shop around (R4) and providers (more concentrated due to R3) overcharge the unlucky to compensate for their losses on covered care. The fixed costs of fighting the system are too high for an individual.

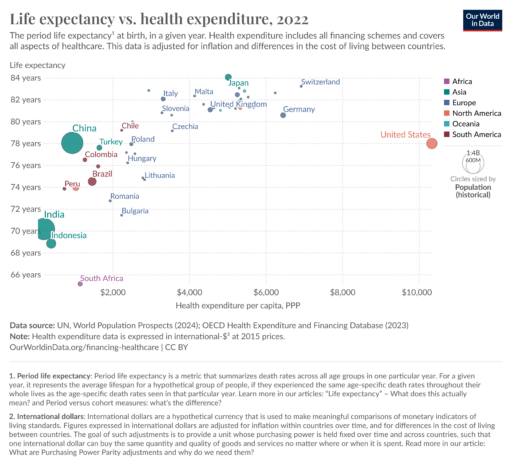

I don’t endorse what Luigi did – it was immoral and ineffective – but I absolutely understand why this system produces rage, violence and the worst bang-for-the-buck in the world.

The insidious thing about the escalating complexity of this system (R1 and R2 again) is that it makes it unfixable. Neither the payers nor the providers can unilaterally arrest this behavior. Nor does tinkering with the rules (as in the ACA) lead to a solution. I don’t know what the right prescription is, but it will have to be something fairly radical: adversaries will have to come together and figure out ways to deliver some real value to consumers, which flies in the face of boardroom pressures for results next quarter.

The insidious thing about the escalating complexity of this system (R1 and R2 again) is that it makes it unfixable. Neither the payers nor the providers can unilaterally arrest this behavior. Nor does tinkering with the rules (as in the ACA) lead to a solution. I don’t know what the right prescription is, but it will have to be something fairly radical: adversaries will have to come together and figure out ways to deliver some real value to consumers, which flies in the face of boardroom pressures for results next quarter.

I will be surprised if the incoming administration dares to wade into this mess without a plan. De-escalating conflict to the benefit of the public is not their forte, nor is grappling with complex systems. Therefore I expect healthcare oligarchy to get worse. I’m not sure what to prescribe other than to proactively do everything you can to stay out of this dysfunctional system.

Meta thought: I think the CLD above captures some of the issues, but like most CLDs, it’s underspecified (and probably misspecified), and it can’t be formally tested. You’d need a formal model to straighten things out, but that’s tricky too: you don’t want a model that includes all the complexity of the current system, because that’s electronic concrete. You need a modestly complex model of the current system and alternatives, so you can use it to figure out how to rewrite the system.