Digitopoly has an interesting take on Greg Mankiw’s Defending the 1%.

You should go read the sources, but Mankiw’s basic scenario is,

Imagine a society with perfect economic equality. … Then, one day, this egalitarian utopia is disturbed by an entrepreneur with an idea for a new product. Think of the entrepreneur as Steve Jobs as he develops the iPod, …. When the entrepreneur’s product is introduced, everyone in society wants to buy it. They each part with, say, $100. The transaction is a voluntary exchange, so it must make both the buyer and the seller better off. But because there are many buyers and only one seller, the distribution of economic well-being is now vastly unequal.

Mankiw goes on to mention but dismiss other drivers, like rent seeking and monopoly. Krugman rejoins with a strong critique, and Digitopoly raises some interesting complications to the innovation policy arguments.

I think the thought experiment, framing the problem as a matter of innovation policy, oversimplifies and misses major drivers of what’s happening. As I wrote in Fortress USA,

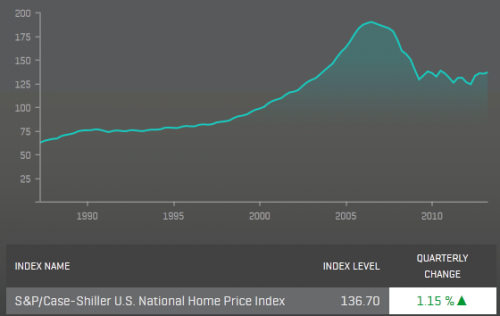

The drivers of rising inequity in the US seem fairly simple. With globalization, capital has become mobile while labor remains tied to geography. So, capital investment flees high wage countries (US) and jobs follow. Asset income goes up, because capital is leveraged by cheaper labor and has good bargaining power among hungry host countries. There’s downward pressure on rich world wages, because with less capital per capita employed, the marginal productivity of labor is lower.

It’s not all bad for the rich world working class, because cheaper goods (WalMart) offset wage losses to some degree. If asset and wage income were uniformly distributed, there might even be a net benefit.

However, asset income and wages aren’t uniformly distributed, so income disparity goes up. Pre-globalization, this wasn’t so noticeable, because there was an implicit deal, in which wage earners knew that, even if they didn’t own all the capital in their country, at least they’d be the beneficiaries of it in some sense through employment and trickle down. Free trade and mobile capital turns the deal into a divorce, which puts a sharp point on questions of property rights allocations that were never quite fair, and sows the seeds of future discontent among the losers.

In addition to disparities in the fate of labor vs. capital, it’s hard not to see abundant rent seeking in the consolidation of firms and the pervasive role of money in government.

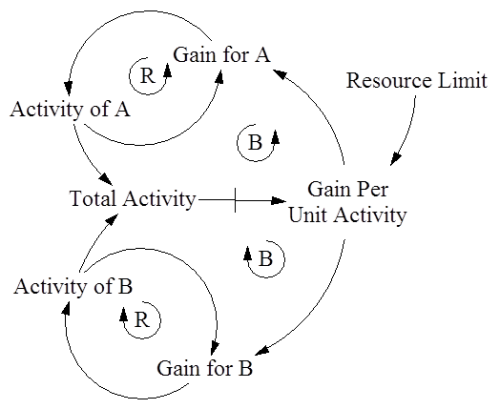

The simple, pure economic thought experiment often brings great insight. But I think this illustrates why models often have to get big before they can get small. Total analytic knowledge of a small model is fairly useless, unless that model encompasses the right structure. It’s hard, a priori, to decide what’s the right structure to include, without distilling that insight from a more complex model.

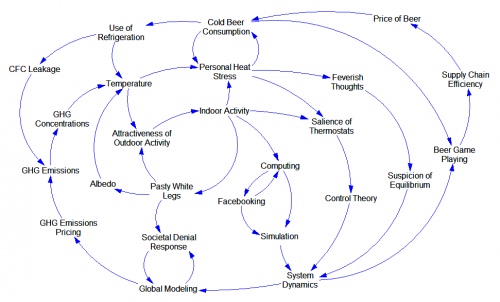

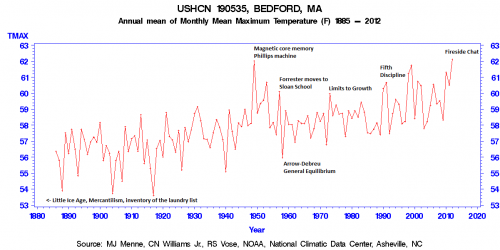

This hardly requires proof, but nevertheless data fully confirm the relationships.

This hardly requires proof, but nevertheless data fully confirm the relationships. I think we can consider this hypothesis definitively proven. All that remains is to put policies in place to ensure the continued health of SD, in order to prevent a global climatic catastrophe.

I think we can consider this hypothesis definitively proven. All that remains is to put policies in place to ensure the continued health of SD, in order to prevent a global climatic catastrophe.

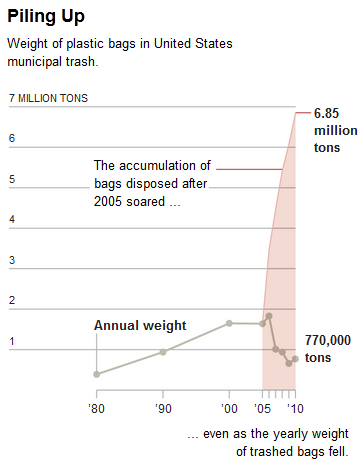

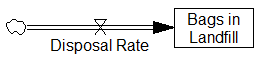

The accumulation of bags in the landfill can only go up, because it has no outflow (though in reality there’s presumably some very slow rate of degradation). The integration in the stock renders

The accumulation of bags in the landfill can only go up, because it has no outflow (though in reality there’s presumably some very slow rate of degradation). The integration in the stock renders