My last post about metaphors ruffled a few feathers. I was a bit surprised, because I thought it was pretty obvious that metaphors, like models, have their limits.

The title was just a riff on the old George Box quote, “all models are wrong, some are useful.” People LOVE to throw that around. I once attended an annoying meeting where one person said it at least half a dozen times in the space of two hours. I heard it in three separate sessions at STIA (which was fine).

I get nervous when I hear, in close succession, about the limits of formal mathematical models and the glorious attributes of metaphors. Sure, a metaphor (using the term loosely, to include similes and analogies) can be an efficient vehicle for conveying meaning, and might lend itself to serving as an icon in some kind of visualization. But there are several possible failure modes:

- The mapping of the metaphor from its literal domain to the concept of interest may be faulty (a bathtub vs. a true exponential decay process).

- The point of the mapping may be missed. (If I compare my organization to the Three Little Pigs, does that mean I’ve built a house of brick, or that there are a lot of wolves out there, or we’re pigs, or … ?)

- Listeners may get the point, but draw unintended policy conclusions. (Do black swans mean I’m not responsible for disasters, or that I should have been more prepared for outliers?)

These are not all that different from problems with models, which shouldn’t really come as a surprise, because a model is just a special kind of metaphor – a mapping from an abstract domain (a set of equations) to a situation of interest – and neither a model nor a metaphor is the real system.

Models and other metaphors have distinct strengths and weaknesses though. Metaphors are efficient, cheap, and speak to people in natural language. They can nicely combine system structure and behavior. But that comes at a price of ambiguity. A formal model is unambiguous, and therefore easy to test, but potentially expensive to build and difficult to share with people who don’t speak math. The specificity of a model is powerful, but also opens up opportunities for completely missing the point (e.g., building a great model of the physics of a situation when the crux of the problem is actually emotional).

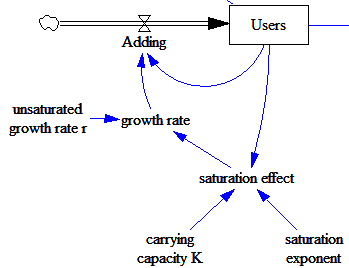

I’m particularly interested in models for their unique ability to generate reliable predictions about behavior from structure and to facilitate comparison with data (using the term broadly, to include more than just the tiny subset of reality that’s available in time series). For example, if I argue that the number of facebook accounts grows logistically, according to dx/dt=r*x*(k-x) for a certain r, k and x(0), we can agree on exactly what that means. Even better, we can estimate r and k from data, and then check later to verify that the model was correct. Try that with “all the world’s a stage.”

If you only have metaphors, you have to be content with not solving a certain class of problems. Consider climate change. I say it’s a bathtub, you say it’s a Random Walk Down Wall Street. To some extent, each is true, and each is false. But there’s simply no way to establish which processes dominate accumulation of heat and endogenous variability, or to predict the outcome of an experiment like doubling CO2, by verbal or visual analogy. It’s essential to introduce some math and data.

Models alone won’t solve our problems either, because they don’t speak to enough people, and we don’t have models for the full range of human concerns. However, I’d argue that we’re already drowning in metaphors, including useless ones (like “the war on [insert favorite topic]”), and in dire need of models and model literacy to tackle our thornier problems.

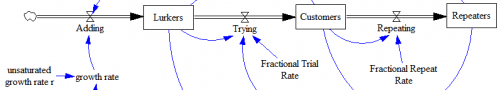

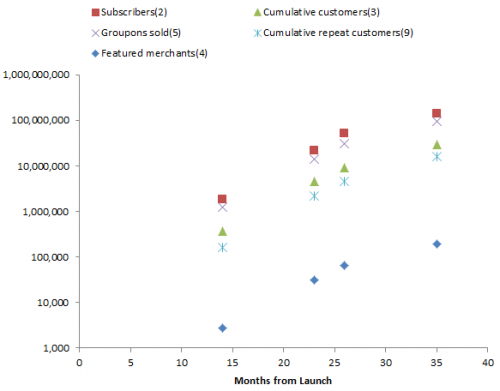

The variable of greatest interest with respect to revenue is Groupons sold. But the others also play a role in determining costs – it takes money to acquire and retain customers. Also, there are actually two populations growing logistically – users and merchants. Growth is presumably a function of the interaction between these two populations. The attractiveness of Groupon to customers depends on having good deals on offer, and the attractiveness to merchants depends on having a large customer pool.

The variable of greatest interest with respect to revenue is Groupons sold. But the others also play a role in determining costs – it takes money to acquire and retain customers. Also, there are actually two populations growing logistically – users and merchants. Growth is presumably a function of the interaction between these two populations. The attractiveness of Groupon to customers depends on having good deals on offer, and the attractiveness to merchants depends on having a large customer pool.