Today, Drew Jones and I presented a simple model as part of the Tällberg Forum’s Washington Conversation, ‘The climate deal we need.’ Our goal was to build from some simple points about the bathtub dynamics of the carbon cycle and climate to yield some insights about what’s needed. Our aspirational list of insights to get across included,

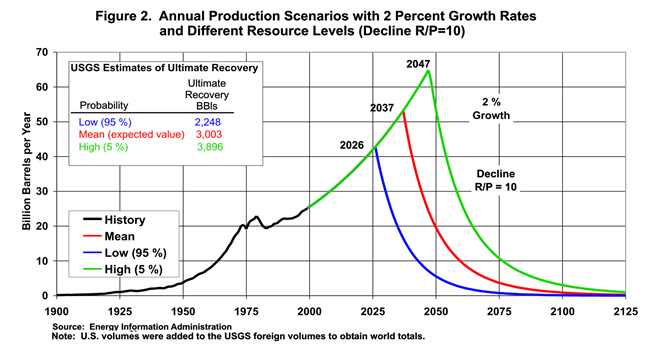

- stabilizing emissions near current levels fails to stabilize atmospheric concentrations any time soon (because emissions now exceed uptake of carbon; stabilization continues that condition, and the residual accumulates in the atmosphere)

- achieving stabilization of atmospheric CO2 at low levels (Hansen et al.’s 350 ppm) requires very aggressive cuts (for the same reason; if carbon cycle feedbacks from temperature kick in, negative emissions could be needed)

- current policies are not on track to meaningful reductions (duh)

- nevertheless, there is a path (Hansen et al.’s “where should humanity aim” paper lays out one option, and there are others)

- starting soon is essential (the bathtub continues to fill while we delay – a costly gamble)

- international negotiation dynamics are tricky due to diversity of interests, coupled problem spaces, and difficulty of transfers (simulations shadow this)

- but everyone has to be on board or little happens (any one major region or sector, uncontrolled, can blow the deal by emitting above natural uptake)

A good moment came when someone asked, “Why should we care about staying below some temperature threshold?” (I think a scenario with about 3.5C was on the screen at the time). Jim Hansen answered, “because that would be a different planet.”

The conversation didn’t lead to specification of “the deal we need” but it explored a number of interesting facets, which I’ll relate in a few follow-on posts.