Over on the Vensim forum, Jean-Jacques Laublé points out an interesting bug in the World3 population sector. His forum post includes the model, with a revealing extreme conditions test and a correction. I think it’s important enough to copy my take here:

This is a very interesting discovery. The equations in question are:

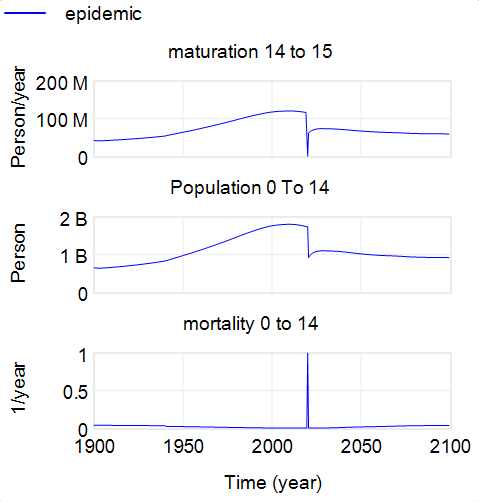

maturation 14 to 15 = ( ( Population 0 To 14 ) ) * ( 1 - mortality 0 to 14 ) / 15 Units: Person/year The fractional rate at which people aged 0-14 mature into the next age cohort (MAT1#5). ************************************************************** mortality 0 to 14= IF THEN ELSE(Time = 2020 * one year, 1 / one year, mortality 0 to 14 table ( life expectancy/one year ) ) Units: 1/year The fractional mortality rate for people aged 0-14 (M1#4). **************************************************************(The second is the one modified for the pulse mortality test.)

In the ‘maturation 14 to 15′ equation, the obvious issue is that ’15’ is a hidden dimensioned parameter. One might argue that this instance is ‘safe’ because 15 years is definitionally the residence time of people in the 0 to 15 cohort – but I would still avoid this usage, and make the 15 yrs a named parameter, like “child cohort duration”, with a corresponding name change to the stock. If nothing else, this would make the structure easier to reuse.

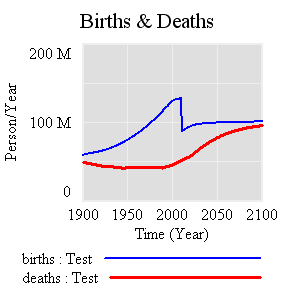

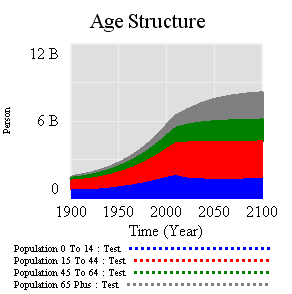

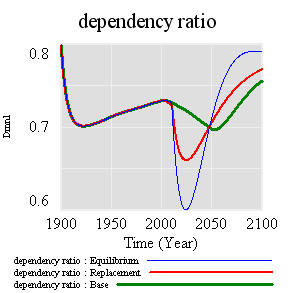

The sneaky bit here, revealed by JJ’s test, is that the ‘1’ in the term (1 – mortality 0 to 14) is not a benign dimensionless number, as we often assume in constructions like 1/(1+a*x). This 1 actually represents the maximum feasible stock outflow rate, in fraction/year, implying that a mortality rate of 1/yr, as in the test input, would consume the entire outflow, leaving no children alive to mature into the next cohort. This is incorrect, because the maximum feasible outflow rate is 1/TIME STEP, and TIME STEP = 0.5, so that 1 should really be 2 ~ frac/year. This is why maturation wrongly goes to 0 in JJ’s experiment, where some children remain to age into the next cohort.

In addition, this construction means that the origin of units in the equation are incorrect – the ’15’ has to be assumed to be dimensionless for this to work. If we assign correct units to the inputs, we have a problem:

maturation 14 to 15 = ~ people/year/year ( ( Population 0 To 14 ) ) ~ people * ( 1 - mortality 0 to 14 ) ~ fraction/year / 15 ~ 1/yearObviously the left side of this equation, maturation, cannot be people/year/year.

JJ’s correction is:

maturation 14 to 15= ( ( Population 0 To 14 ) ) * ( 1 - (mortality 0 to 14 * TIME STEP)) / size of the 0 to 14 populationIn this case, the ‘1’ represents the maximum fraction of the population that can flow out in a time step, so it really is dimensionless. (mortality 0 to 14 * TIME STEP) represents the fractional outflow from mortality within the time step, so it too is properly dimensionless (1/year * year). You could also write this term as:

( 1/TIME STEP - mortality 0 to 14 ) / (1/TIME STEP)In this case you can see that the term is reducing maturation by the fraction of cohort residents who don’t make it to the next age group. 1/TIME STEP represents the maximum feasible outflow, i.e. 2/year if TIME STEP = 0.5 year. In this form, it’s easy to see that this term approaches 1 (no effect) in the continuous time limit as TIME STEP approaches 0.

I should add that these issues probably have only a tiny influence on the kind of experiments performed in Limits to Growth and certainly wouldn’t change the qualitative conclusions. However, I think there’s still a strong argument for careful attention to units: a model that’s right for the wrong reasons is a danger to future users (including yourself), who might use it in unanticipated ways that challenge the robustness in extremes.