Since it was the Breakthrough analysis that got me started on this topic, I took a quick look at it again. Their basic objection is:

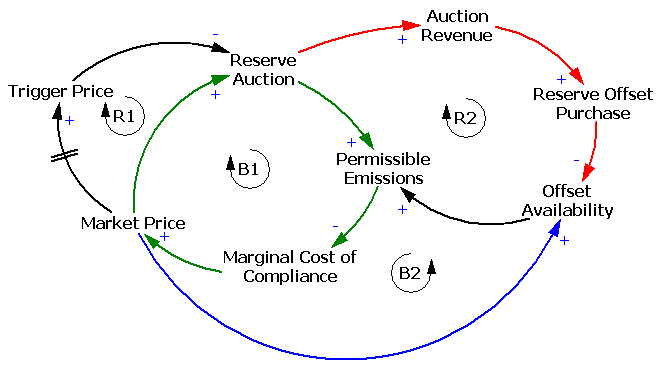

Therein lies a Catch-22 of ACES: if the annual use of up to 2 billion tons of offsets permitted by the bill is limited due to a restricted supply of affordable offsets, the government will pick up the slack by selling reserve allowances, and “refill” the reserve pool with international forestry offset allowances later. […]

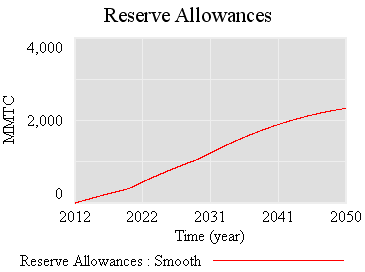

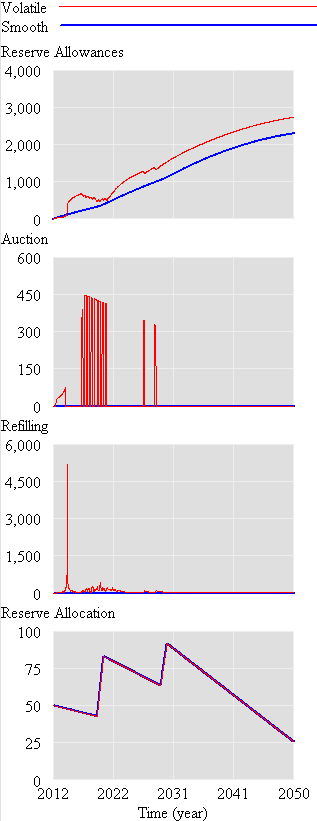

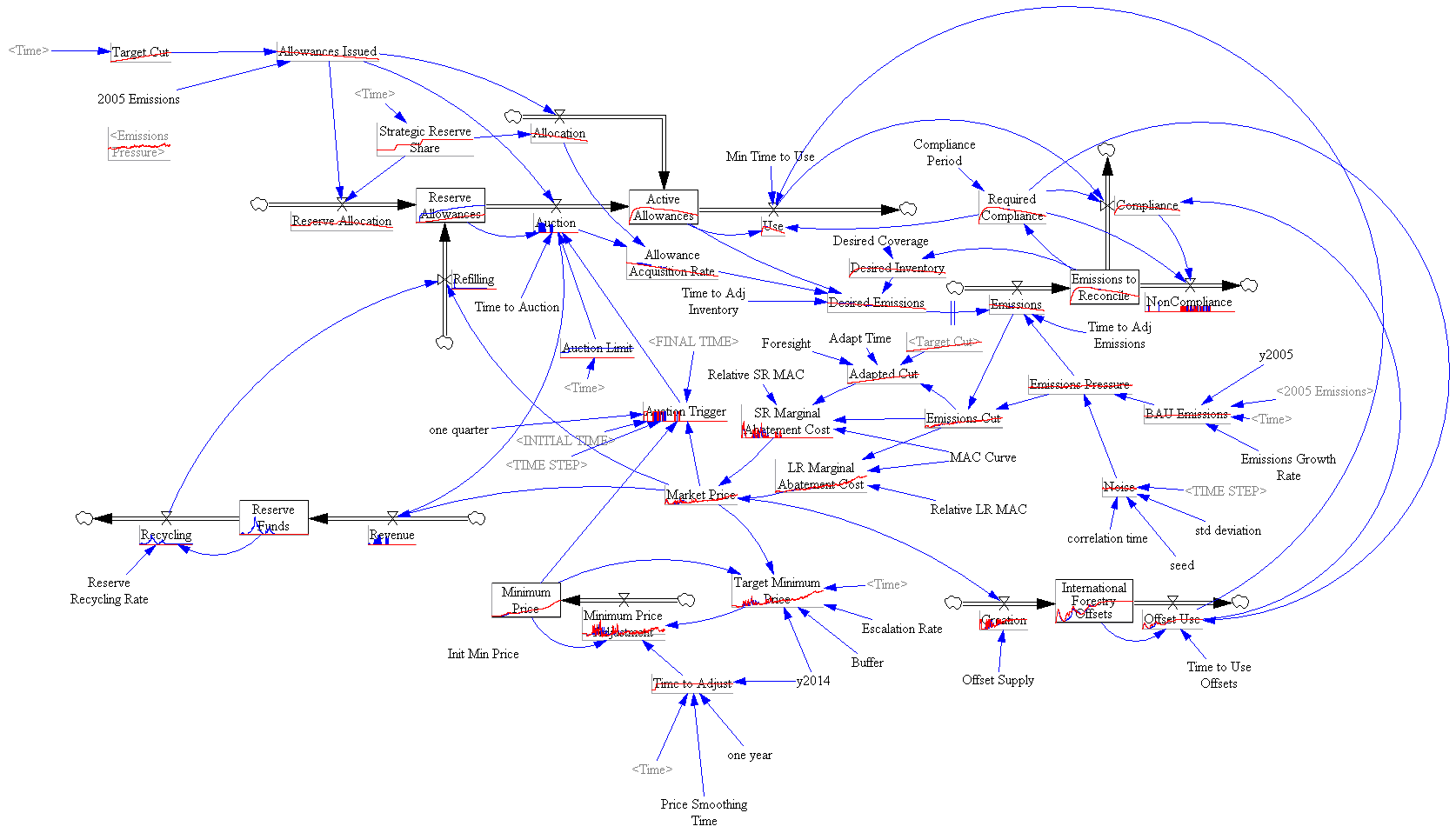

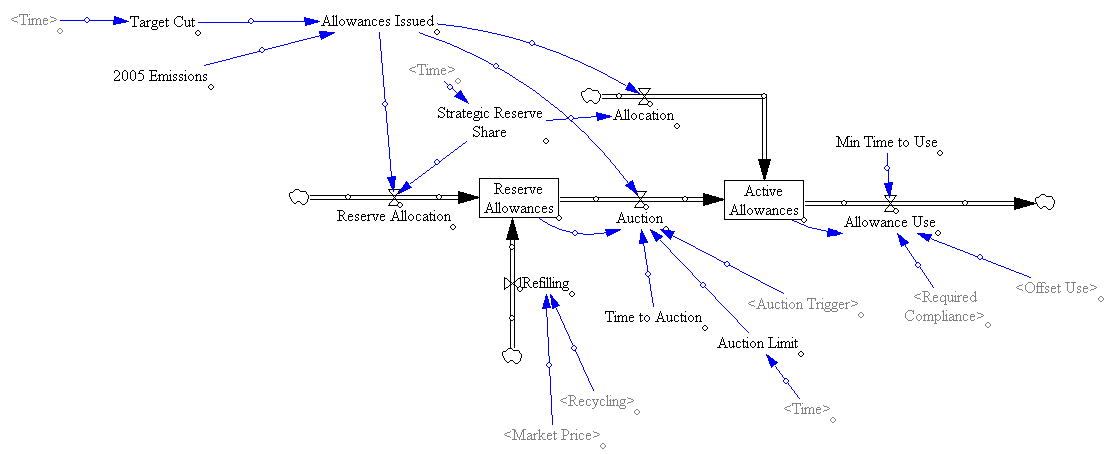

The strategic allowance reserve would be established by taking a certain percentage of allowances originally reserved for the future — 1% of 2012-2019 allowances, 2% of 2020-2029 allowances, and 3% of 2030-2050 allowances — for a total size of 2.7 billion allowances. Every year throughout the cap and trade program, a certain portion of this reserve account would be available for purchase by polluters as a “safety valve” in case the price of emission allowances rises too high.

How much of the reserve account would be available for purchase, and for what price? The bill defines the reserve auction limit as 5 percent of total emissions allowances allocated for any given year between 2012-2016, and 10 percent thereafter, for a total of 12 billion cumulative allowances. For example, the bill specifies that 5.38 billion allowances are to be allocated in 2017 for “capped” sectors of the economy, which means 538 million reserve allowances could be auctioned in that year (10% of 5.38 billion). In other words, the emissions “cap” could be raised by 10% in any year after 2016.

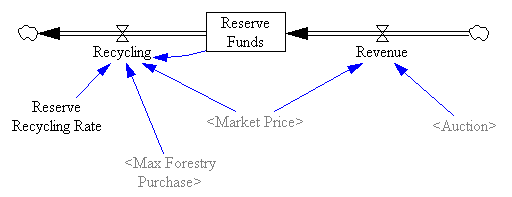

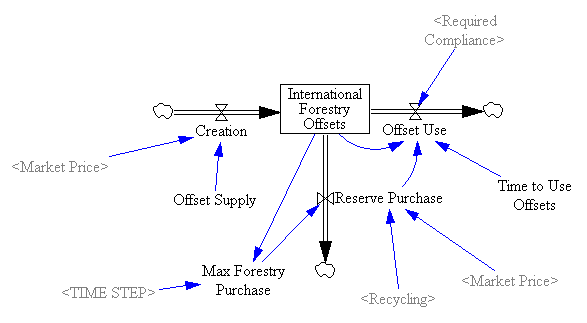

First, it’s not clear to me that international offset supply for refilling the reserve is unlimited. Section 726 doesn’t say they’re unlimited, and a global limit of 1 to 1.5 GtCO2eq/yr applies elsewhere. Anyhow, given the current scale of the offset market, it’s likely that reserve refilling will be competing with market participants for a limited supply of allowances.

Second, even if offset refills do raise the de facto cap, that doesn’t raise global emissions, except to the extent that offsets aren’t real, additional and all that. With perfect offsets, global emissions would go down due to the 5:4 exchange ratio of offsets for allowances. If offsets are really rip-offsets, then W-M has bigger problems than the strategic reserve refill.

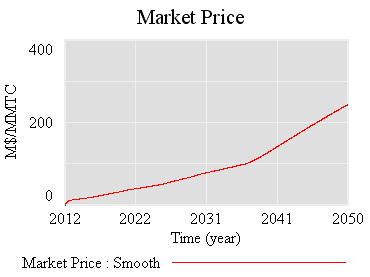

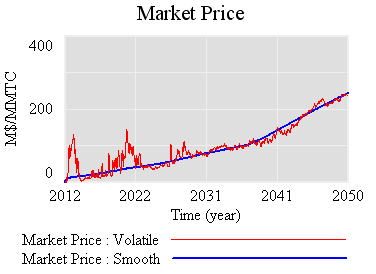

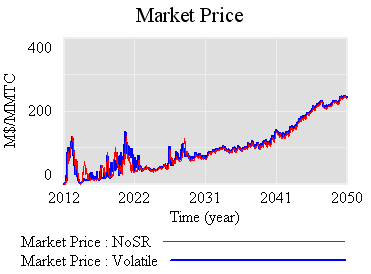

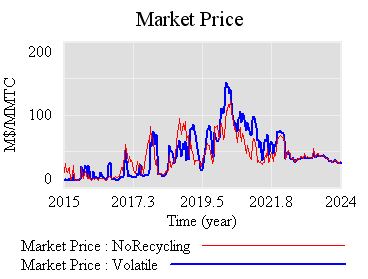

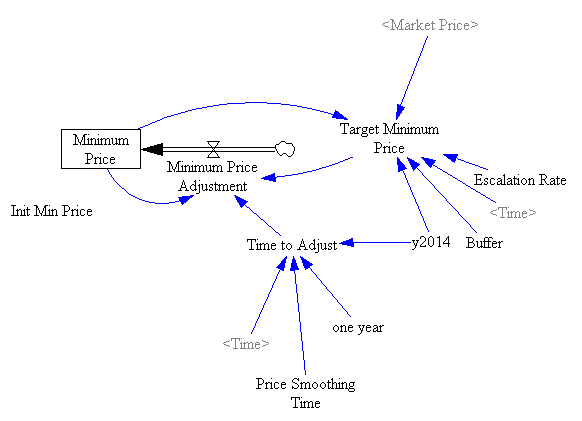

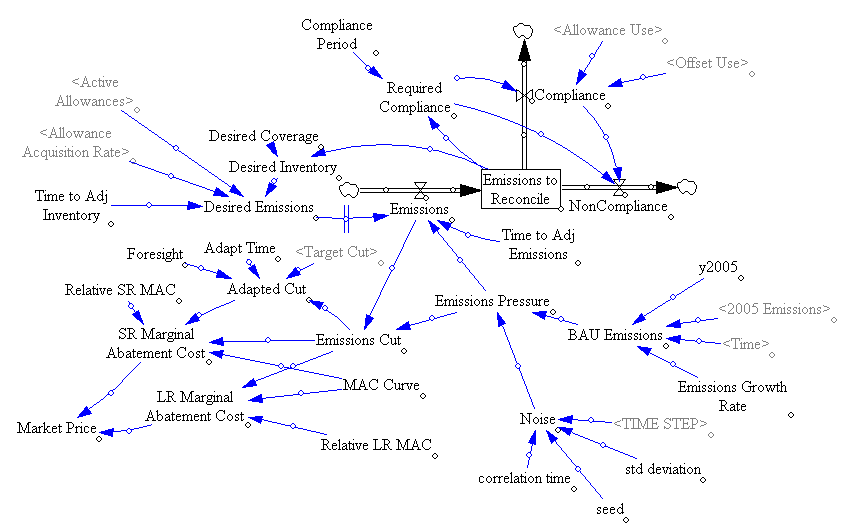

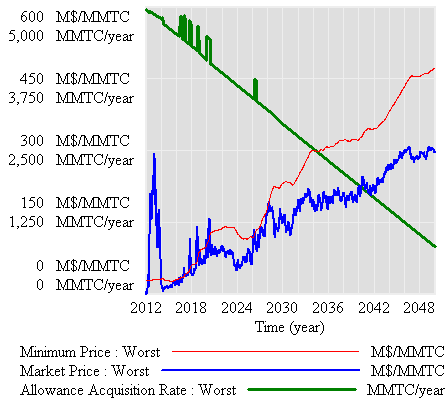

Third, and most importantly, the problem isn’t oversupply of allowances through the reserve. Instead, it’s hard to get allowances out of the reserve – they check in, and never check out. Simple math suggests, and simulations confirm, that it’s hard to generate a price trajectory yielding sustained auction release. Here’s a test with 3%/yr BAU emissions growth and 10% underlying demand volatility:

Even with these implausibly high drivers, it’s hard to get a price trajectory that triggers a sustained auction flow, and total allowance supply (green) and emissions hardly differ from from the no-reserve case.

My preliminary simulation experiments suggest that it’s very unlikely that Breakthrough’s nightmare, a 10% cap violation, could really occur. To make that happen overall, you’d need sustained price increases of over 20% per year – i.e., an allowance price of $56,000/TonCO2eq in 2050. However, there are lesser nightmares hidden in the convoluted language – a messy program to administer, that in the end fails to mitigate volatility.