A friend (who shall remain nameless to avoid persecution) relates:

I just have to share a somewhat funny, mostly frustrating story. XXX and I went to Montreal to see U2 last night …

So at the end of the show, it started raining. Not a light rain but a sharp, arctic windy rain to the point we were all saturated within minutes. No exaggeration. It took us 2 hours to get out of the stadium, to the Metro, and back to the hotel because there were 80,000 people trying to get out. It was purgatory. It was after 3 am before we finally got to sleep.

OK, that’s not the story either. My point, besides sharing the night with you, is to explain my state of mind leading up to the customs experience. At the border, things were going smoothly … until the security guard asked us what we do for work. When I told him what I do, he retorted, “Global warming is not happening. Have you seen the cold weather we’ve had for the past five years?” Of course, I couldn’t let that just sit there. I explained climate change is not just warmer weather but more extreme events and weather is different from climate. So then we actually started arguing about this and I got all fired up …

Now the frustrating part. As we drove away, though, I just felt so despondent that this is the battle with much of the public that we face. How can we convince people to act and to demand their government to act when they really don’t think there is a problem? I’ve been thinking we should utilize some of our time to reach out to the masses who are not looking to improve their mental models of climate change because they don’t even think such a thing exists. …

The fundamental problem, I think, is that evidence for climate change relies on a variety of measurements dispersed over the globe, and physics and models at a variety of levels of complexity. Yet neither of these is accessible to ordinary people. Therefore, when presented with a mix of inconvenience of reducing emissions, false balance, and pseudoscience, people default to a “trust no one” approach, only believing what they can perceive with their own senses: local weather.

That’s a problem, for several reasons. First, local weather is extremely noisy, and only loosely correlated with global energy balance. So, even a person with unbiased weather perception and perfect recall over a long time period really shouldn’t be drawing any conclusions about global conditions from local measurements.

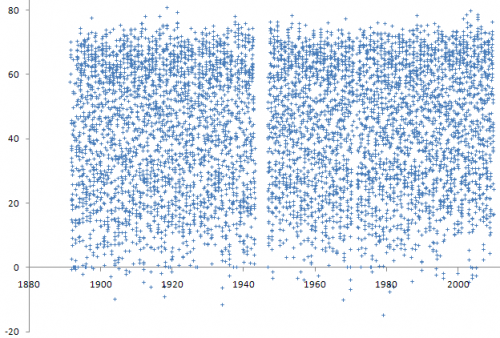

Second, no one has unbiased perception and perfect recall over long periods. Consider the “cold weather we’ve had for the past five years.” Here’s the temperature from the USHCN Enosburg Falls, VT station, near the border crossing, from 1891 through the end of 2009, in degrees Fahrenheit:

It’s hard to imagine something happening in 2010 and 2011 that could lead one to feel good about conclusively calling a 5-yr cold spell. In fact, almost the only thing you can see here is a slight upward trend.

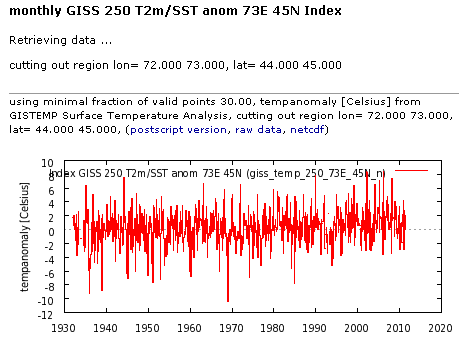

As a check, here’s the GISTEMP 250km anomaly for the region (roughly between Montreal and Burlington, VT):

Source: KNMI Climate Explorer

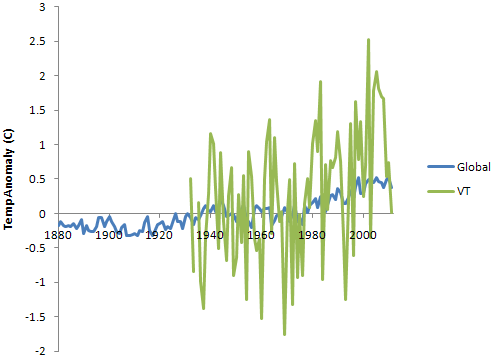

Hard to get much signal out of that noise either. If you annualize, and compare with the global anomaly, a possible explanation emerges:

There’s a definite downward trend from 2006, with 2011 about 2C cooler. Obviously this doesn’t rise out of the noise, or represent global conditions very well, but if mental models use a short averaging time and fail to distinguish noise from structure, this might account for the guard’s impression.

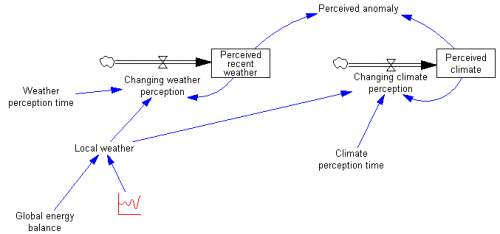

My first cut at articulating the mental model at work looks like this:

This is just a variation of an anchoring and adjustment scheme. The perceived anomaly (or perhaps trend) is a function of one’s understanding of long-term climate, and one’s perception of recent weather. Perceived recent weather adjusts rapidly toward actual conditions, while perceived climate is a slow-moving anchor, that adjusts only gradually toward actual conditions. There are a number of potential problems here.

The worst is that the Climate perception time is likely to be too short (5 years at most?) for drawing valid conclusions about climate. Memories fade, people move every few years, a lot of people don’t get out much so they infrequently sample the real distribution, and many simply aren’t old enough to have experienced much climate, even if they could remember it. If the effective adjustment time is short, then we have the boiled frog syndrome – people will never perceive much change in temperature, because they adjust their baseline expectations towards current conditions too fast.

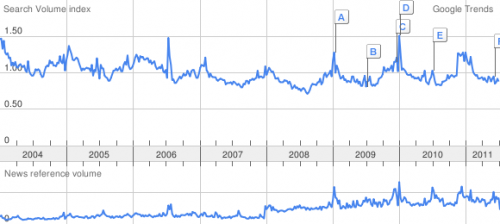

Another big challenge is seasonality. The structure above only makes sense if you feed it deseasonalized temperatures, but it’s unlikely that people are very good at removing seasonal signals. My guess is that, if you could measure it adequately, belief in global warming is higher in summer than in winter. There’s certainly a seasonal pattern to interest in temperature:

It’s also quite possible for other variables to contradict the impression given by temperature. Here’s snowfall in Enosburg Falls:

This is all a long way of saying that there are abundant opportunities for bias and lag to creep into individual perceptions of climate. This would be mitigated somewhat if news focused on any aspect of the long view other than extreme events, but when’s the last time you saw a 100-yr time series graph in a weather report?

Regardless of what’s really going on with climate, it’s hard to have an intelligent conversation about it without agreement on an appropriate attitude toward local data. If a mysterious anecdotal 5-year cooling trend constitutes evidence for global cooling, then we might as well consider a decline in Microsoft stock as evidence for the bankruptcy of capitalism.

Pilots are carefully trained to rely on their instruments when visibility is poor, because their seat of the pants impression of their aircraft’s state is likely to be catastrophically wrong. I think we need the equivalent of pilots’ spatial disorientation training for citizens involved in complex debates. The way to get at this may be to tackle the general problems of cognitive biases, rather than starting with climate in particular. That approach ought to have widespread value for people, irrespective of ideology. The question, then, is how to get good ideas out fast enough to make a difference on the time scale needed to solve urgent problems?

(Of course, while some of us try to make models and data accessible, others are busy trying to make things as confusing as possible, as debunked here.)

Brain Bugs: How the Brain’s Flaws Shape Our Lives by neuroscientist Dean Buonomano.

People are pre-programed to first use our emotional, intuition or whatever you want to call our non-thinking brain. People have a natural reaction of denial. All the data, systems science, analysis, explaining, correcting what people say and other attempts to influence are not going to work when attempting to change people’s behavior to adapt to climate change consequences.

Only when our very survival is threatened will the majority of people react and then only some will survive.

Hopefully you’re wrong, but so far the evidence suggests that you’re right.

I’m curious what the evolutionary advantage of denial is. Perhaps it’s a necessary side effect of cognitive filtering ( https://metasd.com/2011/05/the-danger-of-path-dependent-information-flows-on-the-web/ )? Or maybe, until recently, the benefits of staying in good graces within one’s social circle outweighed the collective dangers of groupthink?

Forty years ago there was a lot of optimism, that modeling would free us of some of these biases. But they seem to be alive and well, and models of all flavors are still just a tiny corner of reality.

“we might as well consider a decline in Microsoft stock as evidence for the bankruptcy of capitalism,” what a great line. I’m assuming you’ll be at the SD conference at the end of the month? I would love to chat some.

Didn’t see the other comments since I’d opened this earlier in my browser and just now had time to read.

I can agree that in the aggregate people may be driven by the “non-thinking” brain, but it’s obviously not the case with everyone. The question for me then is whether or not it’s genetic differences, or simply learning to out think instincts. Perhaps a little of both, but the latter does imply that optimism isn’t completely unfounded.

You can probably guess where I sit.

One of my favorite books on “scientific approach” by Carl sagan, the autor of “Cosmos”

Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark. 1996, “It explains methods to help distinguish between ideas that are considered valid science, and ideas that can be considered pseudoscience (from Wiki)”