Is Groupon overvalued too? Modeling Groupon actually proved a bit more challenging than my last post on Facebook.

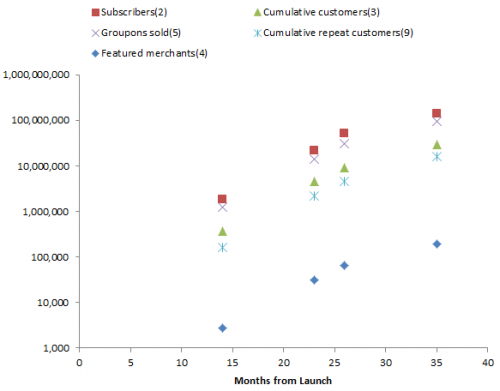

Again, I followed in the footsteps of Cauwels & Sornette, starting with the SEC filing data they used, with an update via google. C&S fit a logistic to Groupon’s cumulative repeat sales. That’s actually the end of a cascade of participation metrics, all of which show logistic growth:

The variable of greatest interest with respect to revenue is Groupons sold. But the others also play a role in determining costs – it takes money to acquire and retain customers. Also, there are actually two populations growing logistically – users and merchants. Growth is presumably a function of the interaction between these two populations. The attractiveness of Groupon to customers depends on having good deals on offer, and the attractiveness to merchants depends on having a large customer pool.

The variable of greatest interest with respect to revenue is Groupons sold. But the others also play a role in determining costs – it takes money to acquire and retain customers. Also, there are actually two populations growing logistically – users and merchants. Growth is presumably a function of the interaction between these two populations. The attractiveness of Groupon to customers depends on having good deals on offer, and the attractiveness to merchants depends on having a large customer pool.

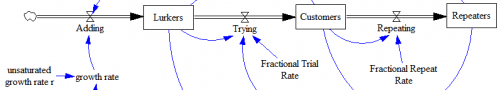

I decided to start with the customer side. The customer supply chain looks something like this:

Subscribers data includes all three stocks, cumulative customers is the right two, and cumulative repeat customers is just the rightmost.

Subscribers data includes all three stocks, cumulative customers is the right two, and cumulative repeat customers is just the rightmost.

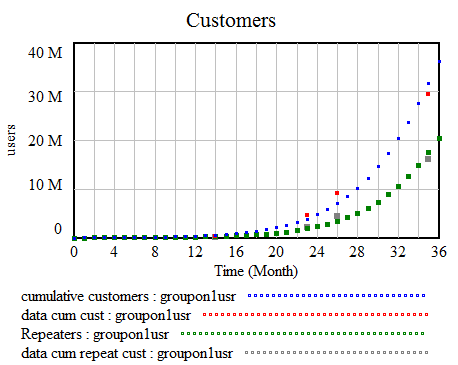

When I first built the model, the logistic dynamics operated at the level of total subscribers – growth created additions of Lurkers (people who are signed up but haven’t participated in a Groupon). Then Lurkers converted at constant fractional rates into Customers and Repeaters. That results in a ridiculously high forecast for the ultimate number of repeat customers, because everyone who ever registers for Groupon eventually becomes a repeat customer. That means a forecast of about 200 million repeat customers eventually (vs. 17 to 27 million in C&S). That doesn’t actually fit the data, because it misses the falloff in growth as participation saturates, but it would be easy to miss if you look at the model vs. data in linear space (rather than logarithmic scaling):

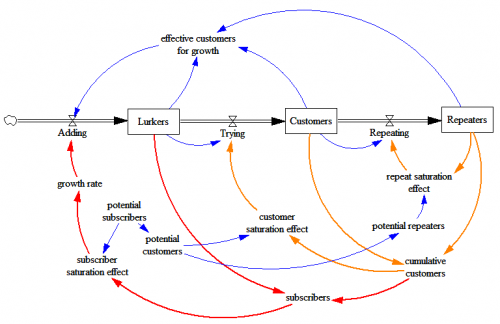

Fortunately, my payoff functions are effectively operating in log scale, so I did notice, and revised the model accordingly. To the subscriber saturation effect (red) I added two additional processes (orange), capturing the fact that (1) not all lurkers who register for Groupon will ever be interested enough to participate, and (2) not everyone who tries a Groupon once will be inclined to repeat the exercise.

Fortunately, my payoff functions are effectively operating in log scale, so I did notice, and revised the model accordingly. To the subscriber saturation effect (red) I added two additional processes (orange), capturing the fact that (1) not all lurkers who register for Groupon will ever be interested enough to participate, and (2) not everyone who tries a Groupon once will be inclined to repeat the exercise.

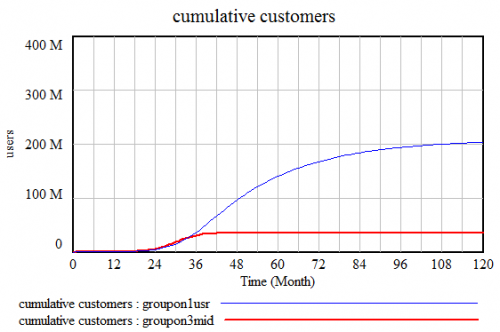

With these additional saturation processes, the model fits the data much better, with about 20% of subscribers ever trying a Groupon, and about 60% of first-time customers ever repeating. That results in a much lower forecast for future customers (and therefore Groupon sales):

With these additional saturation processes, the model fits the data much better, with about 20% of subscribers ever trying a Groupon, and about 60% of first-time customers ever repeating. That results in a much lower forecast for future customers (and therefore Groupon sales):

In the revised model (red, above) cumulative customers saturates at 35 million, and repeat customers at 22 million – roughly in the middle of C&S’ range. This results in slightly higher Groupon unit sales than C&S predict, because first-time sales are included, though over time they become a small fraction of the total flow. There’s also a hint in the data that there’s yet another saturation process, evidenced by a slight decline in the number of repeat Groupons per user, but I didn’t test that.

In the revised model (red, above) cumulative customers saturates at 35 million, and repeat customers at 22 million – roughly in the middle of C&S’ range. This results in slightly higher Groupon unit sales than C&S predict, because first-time sales are included, though over time they become a small fraction of the total flow. There’s also a hint in the data that there’s yet another saturation process, evidenced by a slight decline in the number of repeat Groupons per user, but I didn’t test that.

The real surprise for me was in Groupon’s financials. Groupon has lost money in almost every reported interval; with only a small operating profit in the most recent results (Q3 2011). Revenue has been pretty consistently constant at about $12 per Groupon transaction. So, it looks to me like most of the story about the value of Groupon depends on what you believe about its cost structure, which consists primarily of transaction costs (“cost of revenue”) and sales, general, admin and marketing.

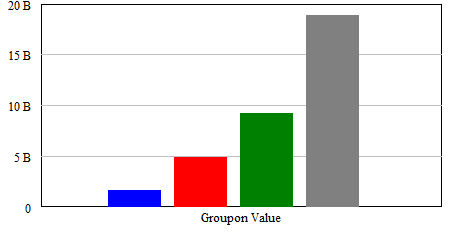

I didn’t dig into this very deeply, but it seems like there are two possible perspectives. Optimistically, most of Groupon’s costs are behind it. In that case, the cost of acquiring customers was high, but now that they’re on board, Groupon can milk them for billions with fairly low transaction and retention costs. There’s actually some evidence for this in the big decline in costs reported in the last quarter. More pessimistically, there are real, ongoing costs associated with finding deals, running transactions, and retaining customers. I ran a few variants to (cartoonishly) value the company:

I found that I really had to push all the levers toward the optimistic end of the spectrum to justify today’s $15 billion market capitalization of the company, even with a middle-of-the-road user forecast and favorable discounting. It’s not impossible, but seems unlikely. If I were putting money at stake, I’d want to know a lot more about the real cost structure, which is potentially tricky given the opportunities for creative accounting raised by the firm’s positive cash float. I’d also want to dig deeper into the merchant population and prospects for expansion into new markets that might not be evident from looking at the existing user populations.

I found that I really had to push all the levers toward the optimistic end of the spectrum to justify today’s $15 billion market capitalization of the company, even with a middle-of-the-road user forecast and favorable discounting. It’s not impossible, but seems unlikely. If I were putting money at stake, I’d want to know a lot more about the real cost structure, which is potentially tricky given the opportunities for creative accounting raised by the firm’s positive cash float. I’d also want to dig deeper into the merchant population and prospects for expansion into new markets that might not be evident from looking at the existing user populations.

As usual, the models are in my library.

Hello, I am very interested in this model of yours. Could you please lend it to me for reference?

Thank you very much!

See link at end of article.