NPR has a nice piece on the US natural gas boom.

Henry Jacoby, an economist at the Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research at MIT, says cheap energy will help pump up the economy.

“Overall, this is a great boon to the United States,” he says. “It’s not a bad thing to have this new and available domestic resource.” He says cheap energy can boost the economy, and he notes that natural gas is half as polluting as coal when it’s burned for electricity.

“But we have to keep our eye on the ball long-term,” Jacoby says. He’s concerned about how cheap gas will affect much cleaner sources of energy. Wind and solar power are more expensive than natural gas, and though those prices have been coming down, they’re chasing a moving target that has fallen fast: natural gas.

“It makes the prospects for large-scale expansion of those technologies more chancy,” Jacoby says.

From an environmental perspective, natural gas could help transition our economy from fossil fuels to clean energy. It’s often portrayed as a bridge fuel to help us through the transition, because it’s so much cleaner than coal and it’s abundant. But Jacoby says that bridge could be in trouble if cheap gas kills the incentive to develop renewable industry.

“You’d better be thinking about a landing of the bridge at the other end. If there’s no landing at the other end, it’s just a bridge to nowhere,” he says.

(For those who don’t know, Jake Jacoby is not a warm-fuzzy greenie; he’s a hard line economist who leads a big general equilibrium modeling project, but also takes climate science seriously).

For me, the key takeaways are:

- Gas beats coal, and may have other useful roles to play. For example, gas backup might be a low-capital-cost complement to variable renewables, with minor emissions consequences.

- It’s better to have more resources than less.

- Whether the opportunity of greater resources translates into a benefit depends on whether the price of gas accounts for full costs.

The last item is a problem. In the US, the price of greenhouse emissions from gas (or anything else) is approximately zero. The effective prices of other environmental consequences – air quality, pollution from fracking, etc. – are also low. Depletion rents for gas are probably also too low, because the abundance of gas is overhyped, and public resources were suboptimally over-allocated decades ago. Low depletion rents encourage a painful boom/bust of gas supply.

Not only physical assets are mispriced. Another part of the story is learning-by-doing, deliberate R&D, and economies of scale – positive feedbacks that grow the market for low-emissions technologies. Firms producing new tech like PV or wind turbines are only able to appropriate part of the profits of their innovations. The rest spills over to benefit society more generally. Too-cheap gas undercuts these reinforcing mechanisms, so gas substitutes aren’t available when scarcity inevitably returns, hence the “bridge to nowhere” dynamic.

Long-term renewable deployment in the U.S. is going to depend primarily on policy. Is there enough concern about environmental consequences to put in place incentives for renewable energy?

– Trevor Houser, energy analyst, Rhodium Group

They key is, what kind of policy? Currently, we rely primarily on performance standards and subsidies. These aren’t getting the job done, for structural reasons. For example, subsidies are self-extinguishing, because they get too expensive to sustain when the target gets too big (think solar feed-in-tariffs in Europe). They’re also politically vulnerable to apparently-cheap alternatives:

“If those prices hang around for another three or four years, then I think you’ll definitely see reduced political will for renewable energy deployment, ” Houser says

The basic problem is that the mindset of subsidizing or requiring “good” technologies makes them feel like luxuries for rich altruists, even though the apparently-cheap alternatives may be merely penny-wise and pound-foolish. The essential alternative is to price the bads, with the logic that people who want to use technologies that harm others ought to at least pay for the privilege. If we can’t manage to do that, I don’t think there’s much hope of getting gas or climate policy right.

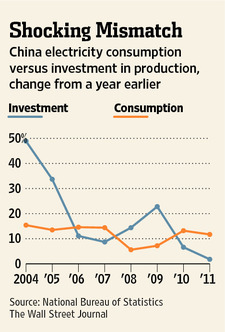

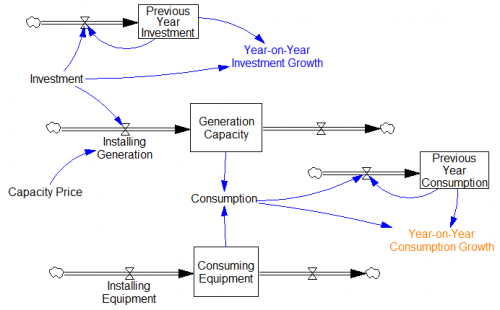

It seems plausible to compare investment and consumption, until you look at the system structure:

It seems plausible to compare investment and consumption, until you look at the system structure:

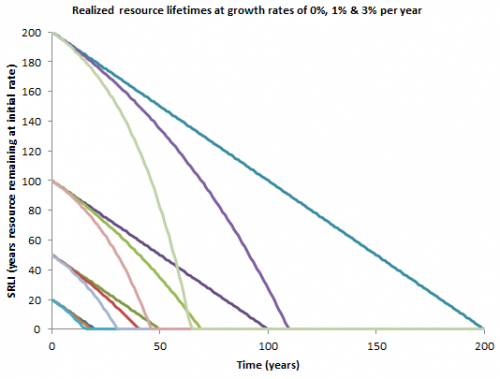

Growth at 3% per year reduces the SRLI of gas from 100 years to a realized lifetime of 45 years, which is not nearly so comfortable. This ought to be intuitive even if you can’t integrate exponentials in your head, because gas consumption would have to roughly double to replace coal (and that doubling would have to happen quickly to meet job claims), so clearly “100 years at current rates” isn’t going to happen.

Growth at 3% per year reduces the SRLI of gas from 100 years to a realized lifetime of 45 years, which is not nearly so comfortable. This ought to be intuitive even if you can’t integrate exponentials in your head, because gas consumption would have to roughly double to replace coal (and that doubling would have to happen quickly to meet job claims), so clearly “100 years at current rates” isn’t going to happen.