A kerfuffle is brewing over Richard Tol’s FUND model (a recent installment). I think this may be one of the first instances of something we’ll see a lot more of: public critique of integrated assessment models.

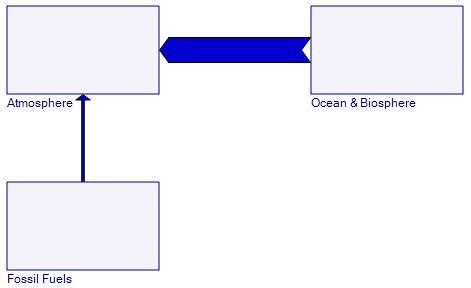

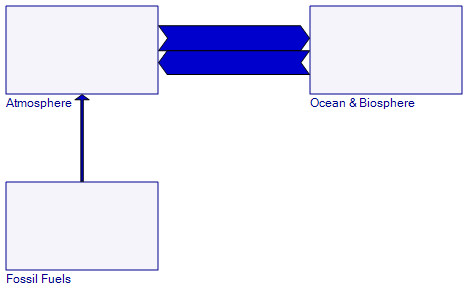

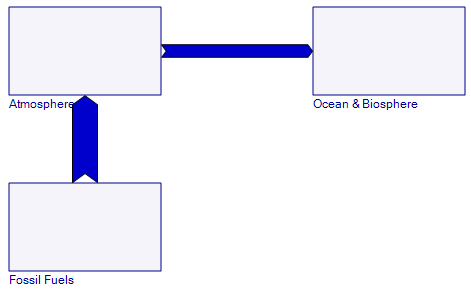

Integrated Assessment Models (IAMs) are a broad class of tools that combine the physics of natural systems (climate, pollutants, etc.) with the dynamics of socioeconomic systems. Most of the time, this means coupling an economic model (usually dynamic general equilibrium or an optimization approach; sometimes bottom-up technical or a hybrid of the two) with a simple to moderately complex model of climate. The IPCC process has used such models extensively to generate emissions and mitigation scenarios.

Interestingly, the IAMs have attracted relatively little attention; most of the debate about climate change is focused on the science. Yet, if you compare the big IAMs to the big climate models, I’d argue that the uncertainties in the IAMs are much bigger. The processes in climate models are basically physics and many are even be subject to experimental verification. We can measure quantities like temperature with considerable precision and spatial detail over long time horizons, for comparison with model output. Some of the economic equivalents, like real GDP, are much slipperier even in their definitions. We have poor data for many regions, and huge problems of “instrumental drift” from changing quality of goods and sectoral composition of activity, and many cultural factors are not even measured. Nearly all models represent human behavior – the ultimate wildcard – by assuming equilibrium, when in fact it’s not clear that equilibrium emerges faster than other dynamics change the landscape on which it arises. So, if climate skeptics get excited about the appropriate centering method for principal components analysis, they should be positively foaming at the mouth over the assumptions in IAMs, because there are far more of them, with far less direct empirical support.

Last summer at EMF Snowmass, I reflected on some of our learning from the C-ROADS experience (here’s my presentation). One of the key points, I think, is that there is a huge gulf between models and modelers, on the one hand, and the needs and understanding of decision makers and the general public on the other. If modelers don’t close that gap by deliberately translating their insights for lay audiences, focusing their tools on decision maker needs, and embracing a much higher level of transparency, someone else will do that translation for them. Most likely, that “someone else” will be much less informed, or have a bigger axe to grind, than the modelers would hope.

With respect to transparency, Tol’s FUND model is further along than many models: the code is available. So, informed tinkerers can peek under the hood if they wish. However, it comes with a warning:

It is the developer’s firm belief that most researchers should be locked away in an ivory tower. Models are often quite useless in unexperienced hands, and sometimes misleading. No one is smart enough to master in a short period what took someone else years to develop. Not-understood models are irrelevant, half-understood models treacherous, and mis-understood models dangerous.

Therefore, FUND does not have a pretty interface, and you will have to make to real effort to let it do something, let alone to let it do something new.

I understand the motivation for this warning. However, it leaves the modeler-consumer gulf gaping.The modelers have their insights into systems, the decision makers have their problems managing those systems, and ne’er the twain shall meet – there just aren’t enough modelers to go around. That leaves reports as the primary conduit of information from model to user, which is fine if your ivory tower is secure enough that you need not care whether your insights have any influence. It’s not even clear that reports are more likely to be understood than models: there have been a number of high-profile instances of ill-conceived institutional press releases and misinterpretation of conclusions and even raw data.

Also, there’s a hint of danger in the very idea of building dangerous models. Obviously all models, like analogies, are limited in their fidelity and generality. It’s important to understand those limitations, just as a pilot must understand the limitations of her instruments. However, if a model is a minefield for the uninitiated user, I have to question its utility. Robustness is an important aspect of model quality; a model given vaguely realistic inputs should yield realistic outputs most of the time, and a model given stupid inputs should generate realistic catastrophes. This is perhaps especially true for climate, where we are concerned about the tails of the distribution of possible outcomes. It’s hard to build a model that’s only robust to the kinds of experiments that one would like to perform, while ignoring other potential problems. To the extent that a model generates unrealistic outcomes, the causes should be traceable; if its not easy for the model user to see in side the black box, then I worry that the developer won’t have done enough inspection either. So, the discipline of building models for naive users imposes some useful quality incentives on the model developer.

IAM developers are busy adding spatial resolution, technical detail, and other useful features to models. There’s comparatively less work on consolidation of insights, with translation and construction of tools for wider consumption. That’s understandable, because there aren’t always strong rewards for doing so. However, I think modelers ignore this crucial task at their future peril.