This weekend I was inexorably drawn to Yellowstone by the earthquake swarm. I didn’t feel anything, but even the benign springs at Mammoth can look frightening. This time of year, you’re a lot more likely to freeze to death than to be obliterated by a supervolcano eruption (I hope).

Category: Skeptics

More on Climate Predictions

No pun intended.

Scott Armstrong has again asserted on the JDM list that global warming forecasts are merely unscientific opinions (ignoring my prior objections to the claim). My response follows (a bit enhanced here, e.g., providing links).

Today would be an auspicious day to declare the death of climate science, but I’m afraid the announcement would be premature.

JDM researchers might be interested in the forecasts of global warming as they are based on unaided subjective forecasts (unaided by forecasting principles) entered into complex computer models.

This seems to say that climate scientists first form an opinion about the temperature in 2100, or perhaps about climate sensitivity to 2x CO2, then tweak their models to reproduce the desired result. This is a misperception about models and modeling. First, in a complex physical model, there is no direct way for opinions that represent outcomes (like climate sensitivity) to be “entered in.” Outcomes emerge from the specification and calibration process. In a complex, nonlinear, stochastic model it is rather difficult to get a desired behavior, particularly when the model must conform to data. Climate models are not just replicating the time series of global temperature; they first must replicate geographic and seasonal patterns of temperature and precipitation, vertical structure of the atmosphere, etc. With a model that takes hours or weeks to execute, it’s simply not practical to bend the results to reflect preconceived notions. Second, not all models are big and complex. Low order energy balance models can be fully estimated from data, and still yield nonzero climate sensitivity.

I presume that the backing for the statement above is to be found in Green and Armstrong (2007), on which I have already commented here and on the JDM list. Continue reading “More on Climate Predictions”

On Limits to Growth

It’s a good idea to read things you criticize; checking your sources doesn’t hurt either. One of the most frequent targets of uninformed criticism, passed down from teacher to student with nary a reference to the actual text, must be The Limits to Growth. In writing my recent review of Green & Armstrong (2007), I ran across this tidbit:

Complex models (those involving nonlinearities and interactions) harm accuracy because their errors multiply. Ascher (1978), refers to the Club of Rome’s 1972 forecasts where, unaware of the research on forecasting, the developers proudly proclaimed, “in our model about 100,000 relationships are stored in the computer.” (page 999)

Setting aside the erroneous attributions about complexity, I found the statement that the MIT world models contained 100,000 relationships surprising, as both can be diagrammed on a single large page. I looked up electronic copies of World Dynamics and World3, which have 123 and 373 equations respectively. A third or more of those are inconsequential coefficients or switches for policy experiments. So how did Ascher, or Ascher’s source, get to 100,000? Perhaps by multiplying by the number of time steps over the 200 year simulation period – hardly a relevant measure of complexity.

Meadows et al. tried to steer the reader away from focusing on point forecasts. The introduction to the simulation results reads,

Each of these variables is plotted on a different vertical scale. We have deliberately omitted the vertical scales and we have made the horizontal time scale somewhat vague because we want to emphasize the general behavior modes of these computer outputs, not the numerical values, which are only approximately known. (page 123)

Many critics have blithely ignored such admonitions, and other comments to the effect of, “this is a choice, not a forecast” or “more study is needed.” Often, critics don’t even refer to the World3 runs, which are inconvenient in that none reaches overshoot in the 20th century, making it hard to establish that “LTG predicted the end of the world in year XXXX, and it didn’t happen.” Instead, critics choose the year XXXX from a table of resource lifetime indices in the chapter on nonrenewable resources (page 56), which were not forecasts at all. Continue reading “On Limits to Growth”

Surveys and Quizzes as Propaganda

Long ago I took an IATA survey to relieve the boredom of a long layover. Ever since, I’ve been on their mailing list, and received “invitations” to take additional surveys. Sometimes I do, out of curiosity – it’s fun to try to infer what they’re really after. The latest is a “Global Survey on Aviation and Environment” so I couldn’t resist. After a few introductory questions, we get to the meat:

History/Fact

1. Air transport contributes 8% to the global economy and supports employment for 32 million people. But, aviation is responsible for only 2% of global CO2 emissions.

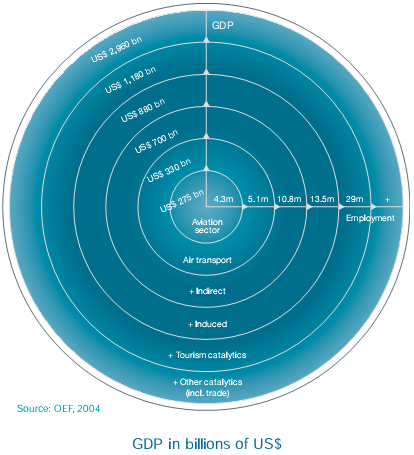

Wow … an energy intensive sector that somehow manages to be less carbon intensive than the economy in general? Sounds too good to be true. Unfortunately, it is. The illusion of massive scale of the air transport sector is achieved by including indirect activity, i.e. taking credit for what other sectors produce when it might involve air transport. Federal cost-benefit accounting practices generally banish the use of such multiplier effects, with good reason. According to an ATAG report hosted by IATA, the indirect effects make up the bulk of activity claimed above. ATAG peels the onion for us:

So, direct air transport is closer to 1% of GDP. Comparing direct GDP of 1% to direct emissions of 2% no longer looks favorable, though – especially when you consider that air transport has other warming effects (contrails, non-CO2 GHG emissions) that might double or triple its climate impact. The IPCC Aviation and the Global Atmosphere report, for example, places aviation at about 2% of fossil fuel use, and about 4% of total radiative forcing. If IATA wants to count indirect GDP and employment, fine with me, but then they need to count indirect emissions on the same basis. Continue reading “Surveys and Quizzes as Propaganda”

Evidence on Climate Predictions

Last Year, Kesten Green and Scott Armstrong published a critique of climate science, arguing that there are no valid scientific forecasts of climate. RealClimate mocked the paper, but didn’t really refute it. The paper came to my attention recently when Green & Armstrong attacked John Sterman and Linda Booth Sweeney’s paper on mental models of climate change.

I reviewed Green & Armstrong’s paper and concluded that their claims were overstated. I responded as follows: Continue reading “Evidence on Climate Predictions”

Confused at the National Post

A colleague recently pointed me to a debate on an MIT email list over Lorne Gunter’s National Post article, Forget Global Warming: Welcome to the New Ice Age.

The article starts off with anecdotal evidence that this has been an unusually cold winter. If it had stopped where it said, “OK, so one winter does not a climate make. It would be premature to claim an Ice Age is looming just because we have had one of our most brutal winters in decades,” I wouldn’t have faulted it. It’s useful as a general principle to realize that weather has high variance, so it’s silly to make decisions on the basis of short term events. (Similarly, science is a process of refinement, so it’s silly to make decisions on the basis of a single paper.)

But it didn’t stop. It went on to assemble a set of scientific results of varying quality and relevance, purporting to show that, “It’s way too early to claim the same is about to happen again, but then it’s way too early for the hysteria of the global warmers, too.” That sounds to me like a claim that the evidence for anthropogenic global warming is of the same quality as the evidence that we’re about to enter an ice age, which is ridiculous. It fails to inform the layman either by giving a useful summary of accurately characterized evidence or by demonstrating proper application of logic.

Some further digging reveals that the article is full of holes: Continue reading “Confused at the National Post”