Several people have pointed out Erle Ellis’ NYT opinion, Overpopulation Is Not the Problem:

MANY scientists believe that by transforming the earth’s natural landscapes, we are undermining the very life support systems that sustain us. Like bacteria in a petri dish, our exploding numbers are reaching the limits of a finite planet, with dire consequences. Disaster looms as humans exceed the earth’s natural carrying capacity. Clearly, this could not be sustainable.

This is nonsense.

…

There really is no such thing as a human carrying capacity. We are nothing at all like bacteria in a petri dish.

In part, this is just a rhetorical trick. When Ellis explains himself further, he says,

There are no environmental/physical limits to humanity.

Of course our planet has limits.

Clear as mud, right?

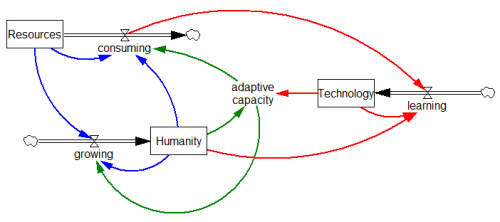

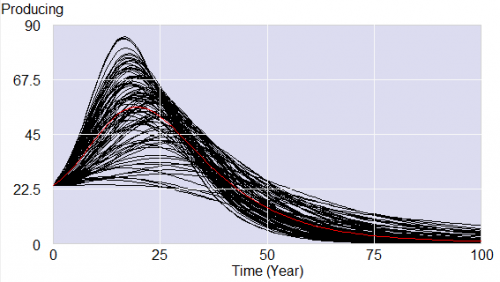

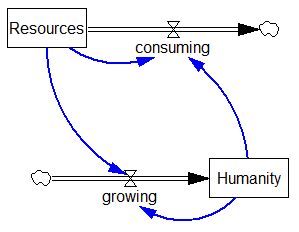

Here’s the petri dish view of humanity:

I don’t actually know anyone working on sustainability who operates under this exact mental model; it’s substantially a strawdog.

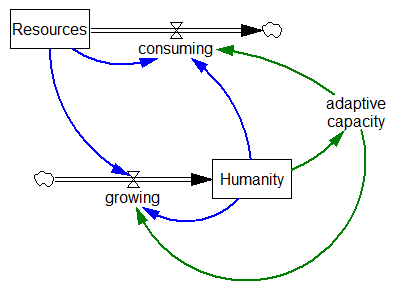

What Ellis has identified is technology.

Yet these claims demonstrate a profound misunderstanding of the ecology of human systems. The conditions that sustain humanity are not natural and never have been. Since prehistory, human populations have used technologies and engineered ecosystems to sustain populations well beyond the capabilities of unaltered “natural” ecosystems.

Well, duh.

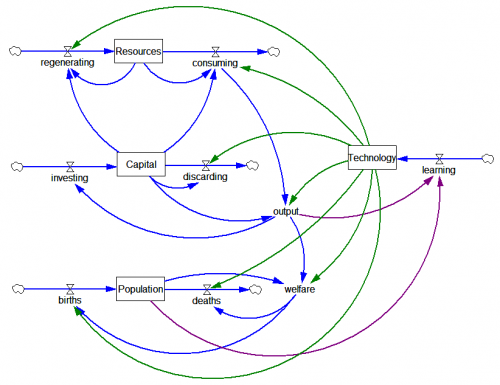

The structure Ellis adds is essentially the green loops below:

Of course, the fact that the green structure exists does not mean that the blue structure does not exist. It just means that there are multiple causes competing for dominance in this system.

Of course, the fact that the green structure exists does not mean that the blue structure does not exist. It just means that there are multiple causes competing for dominance in this system.

Ellis talks about improvements in adaptive capacity as if it’s coincident with the expansion of human activity. In one sense, that’s true, as having more agents to explore fitness landscapes increases the probability that some will survive. But that’s a Darwinian view that isn’t very promising for human welfare.

Ellis glosses over the fact that technology is a stock (red) – really a chain of stocks that impose long delays:

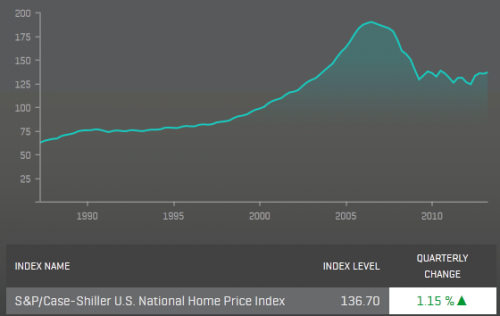

With this view, one must ask whether technology accumulates more quickly than the source/sink exhaustion driven by the growth of human activity. For early humans, this was evidently possible. But as they say in finance, past performance does not guarantee future returns. In spite of the fact that certain technical measures of progress are extremely rapid (Moore’s Law), it appears that aggregate technological progress (as measured by energy intensity or the Solow residual, for example) is fairly slow – at most a couple % per year. It hasn’t been fast enough to permit increasing welfare with decreasing material throughput.

Ellis half recognizes the problem,

Who knows what will be possible with the technologies of the future?

Somehow he’s certain, even in absence of recent precedent or knowledge of the particulars, that technology will outrace constraints.

To answer the question properly, one must really decompose technology into constituents that affect different transformations (resources to economic output, output to welfare, welfare to lifespan, etc.), and identify the social signals that will guide the development of technology and its embodiment in products and services. One should interpret technology broadly – it’s not just knowledge of physics and device blueprints; it’s also tech for organization of human activity embodied in social institutions.

When you look at things this way, I think it becomes obvious that the kinds of technical problems solved by neolithic societies and imperial China could be radically different from, and uninformative about, those we face today. Further, one should take the history of early civilizations, like the Mayans, as evidence that there are social multipliers that enable collapse even in the absence of definitive physical limits. That implies that, far from being irrelevant, brushes with carrying capacity can easily have severe welfare implications even when physical fundamentals are not binding in principle.

The fact that carrying capacity varies with technology does not free us from the fact that, for any given level of technology, it’s easier to deliver a given level of per capita welfare to fewer people rather than more. So the only loops that argue in favor of a larger population involve the links from population to increase learning and adaptive capacity (essentially Simon’s Ultimate Resource hypothesis). But Ellis doesn’t present any evidence that population growth has a causal effect on technology that outweighs its direct material implications. So, one might much better say, “overpopulation is not the only problem.”

Ultimately, I wonder why Ellis and many others are so eager to press the “no limits” narrative.

Most people I know who believe that limits are relevant are essentially advocating internalizing the externalities that comprise failure to recognize limits, to guide market allocations, technology and preferences in a direction that avoids constraints. Ellis seems to be asking for an emphasis on the same outcome, technology or adaptive capacity to evade limits. It’s hard to imagine how one would get such technology without signals that promote its development and adoption. So, in a sense, both camps are pursuing compatible policy agendas. The difference is that proclaiming “no limits” makes it a lot harder to make the case for internalizing externalities. If we aren’t willing to make our desire to avoid limits explicit in market signals and social institutions, then we’re relying on luck to deliver the tech we need. That strikes me as a spectacular failure to adopt one of the major technical breakthroughs of our time, the ability to understand earth systems.

Update: Gene Bellinger replicated this in InsightMaker. Replication is a great way to force yourself to think deeply about a model, and often reveals insights and mistakes you’d never get otherwise (short of building the model from scratch yourself). True to form, Gene found issues. In the last diagram, there should be a link from population to output, and maybe consuming should be driven by output rather than capital, as it’s the use, not the equipment, that does the consuming.