A while back I decided to never buy another garden plant unless I’d first dug the hole for it. In a single stroke, this simple rule eliminated impulse shopping at the nursery, improved the survival rate of new plants, and increased overall garden productivity.

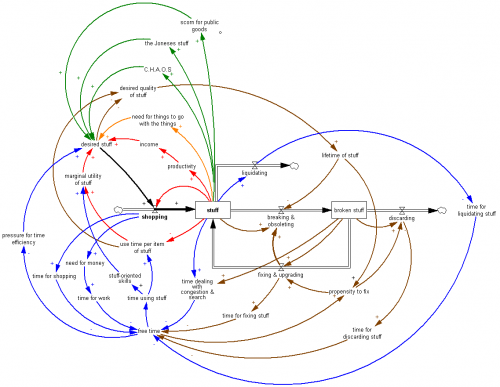

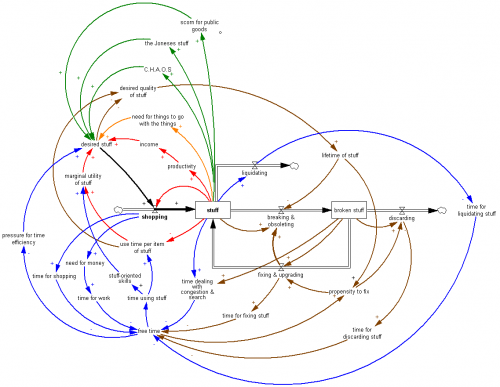

This got me thinking about the insidious dynamics of stuff, by which tools come to rule their masters. I’ve distilled most of my thinking into this picture:

Click to enlarge.

This is mainly a visual post, but here’s a quick guide to some of the loops:

Black: stuff is the accumulation of shopping, less outflows from discarding and liquidation.

Red: Shopping adjusts the stock of stuff to a goal. The goal is set by income (a positive feedback, to the extent that stuff makes you more productive, so you can afford more stuff) and by the utility of stuff at the margin, which falls as you have less and less time to use each item of stuff, or acquire increasingly useless items.

So far, Economics 101 would tell a nice story of smooth adjustment of the shopping process to an equilibrium at the optimal stuff level. That’s defeated by the complexity of all of the other dynamics, which create a variety of possible vicious cycles and misperceptions of feedback that result in suboptimal stuffing.

Orange: You need stuff to go with the stuff. The iPad needs a dock, etc. Even if the stuff is truly simple, you need somewhere to put it.

Green: Society reinforces the need for stuff, via keep-up-with-the-Joneses and neglect of shared stuff. When you have too much stuff, C.H.A.O.S. ensues – “can’t have anyone over syndrome” – which reinforces the desire for stuff to hide the chaos or facilitate fun without social contact.

Blue: Stuff takes time, in a variety of ways. The more stuff you have, the less time you actually have for using stuff for fun. This can actually increase your desire for stuff, due to the desire to have fun more efficiently in the limited time available.

Brown: Pressure for time and more stuff triggers a bunch of loops involving quality of stuff. One response is to buy low-quality stuff, which soon increases the stock of broken stuff lying about, worsening time pressure. One response is the descent into disposability, which saves the time, at the expense of a high throughput (shopping->discarding) relative to the stock of stuff. Once you’re fully stocked with low-quality stuff, why bother fixing it when it breaks? Fixing one thing often results in collateral damage to another (computers are notorious for this).

I’m far from a successful minimalist yet, but here’s what’s working for me to various degrees:

- The old advice, “Use it up, wear it out, make it do or do without” works.

- Don’t buy stuff when you can rent it. Unfortunately rental markets aren’t very liquid so this can be tough.

- Allocate time to liquidating stuff. This eats up free time in the short run, but it’s a worse-before-better dynamic, so there’s a payoff in the long run. Fortunately liquidating stuff has a learning curve – it gets easier.

- Make underutilized and broken stuff salient, by keeping lists and eliminating concealing storage.

- Change your shopping policy to forbid acquisition of new stuff until existing stuff has been dealt with.

- Buy higher quality than you think you’ll need.

- Learn low-stuff skills.

- Require steady state stuff: no shopping for new things until something old goes to make way for it.

- Do things, even when you don’t have the perfect gear.

- Explicitly prioritize stuff acquisition.

- Tax yourself, or at least mentally double the price of any proposed acquisition, to account for all the side effects that you’ll discover later.

- Get relatives to give $ to your favorite nonprofit rather than giving you something you won’t use.

There are also some policies that address the social dimensions of stuff:

- Underdress and underequip. Occasionally this results in your own discomfort, but reverses the social arms race.

- Don’t reward other peoples’ shopping by drooling over their stuff. Pity them.

- Use and promote shared stuff, like parks.

This system has a lot of positive feedback, so once you get the loops running the right way, improvement really takes off.