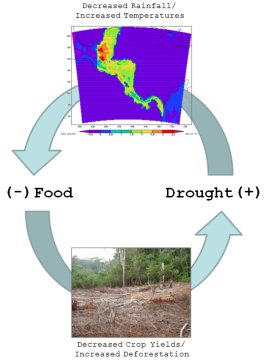

NASA has an interesting article on the fall of the Maya. NASA-sponsored authors used climate models to simulate the effects of deforestation on local conditions. The result: evidence for a positive feedback cycle of lower yields, requiring greater deforestation to increase cultivated area, causing drought and increased temperatures, further lowering yields.

“They did it to themselves,” says veteran archeologist Tom Sever.

…

A major drought occurred about the time the Maya began to disappear. And at the time of their collapse, the Maya had cut down most of the trees across large swaths of the land to clear fields for growing corn to feed their burgeoning population. They also cut trees for firewood and for making building materials.

“They had to burn 20 trees to heat the limestone for making just 1 square meter of the lime plaster they used to build their tremendous temples, reservoirs, and monuments,” explains Sever.

…

“In some of the Maya city-states, mass graves have been found containing groups of skeletons with jade inlays in their teeth – something they reserved for Maya elites – perhaps in this case murdered aristocracy,” [Griffin] speculates.

No single factor brings a civilization to its knees, but the deforestation that helped bring on drought could easily have exacerbated other problems such as civil unrest, war, starvation and disease.

An SD Conference article by Tom Forest fills in some of the blanks on the other problems:

… this paper illustrates how humans can politically intensify resource shortages into universal disaster.

In the current model, the land sector has two variables. One is productivity, which is exhausted by people but regenerates over a period of time. The other… is Available Land. When population exceeds carrying capacity, warfare frequency and intensity increase enough to depopulate land. In the archaeological record this is reflected by the construction of walls around cities and the abandonment of farmlands outside the walls. Some land becomes unsafe to use because of conflict, which then reduces the carrying capacity and intensifies warfare. This is an archetypal death spiral. Land is eventually reoccupied, but more slowly than the abandonment. A population collapse eventually hastens the recovery of productivity, so after the brief but severe collapse growth resumes from a much lower level.

…

The key dynamic is that people do not account for the future impact of their numbers on productivity, and therefore production, when they have children. Nor does death by malnutrition and starvation have an immediate effect. This leads to an overshoot, as in the Limits to Growth, but the policy response is warfare proportionate to the shortfall, which takes more land out of production and worsens the shortfall.

Put another way, in the growth phase people are in a positive-sum game. There is more to go around, more wealth to share, and population increase is unhindered by policy or production. But once the limits are reached, people are in a zero-sum game, or even slightly negative-sum. Rather than share the pain, people turn on each other to increase their personal share of a shrinking pie at the expense of others. The unintended consequence-the fatal irony-is that by doing so, the pie shrinks much faster than it would otherwise. Apocalypse is the result.

Making climate endogenous in Forest’s model would add another positive feedback loop, deepening the trap for a civilization that crosses the line from resource abundance to scarcity and degradation.