China’s one child policy is at its 30th birthday. Inside-Out China has a quick post on the debate over the future of the policy. That caught my interest, because I’ve seen recent headlines calling for an increase in China’s population growth to facilitate dealing with an aging population – a potentially disastrous policy that nevertheless has adherents in many countries, including the US.

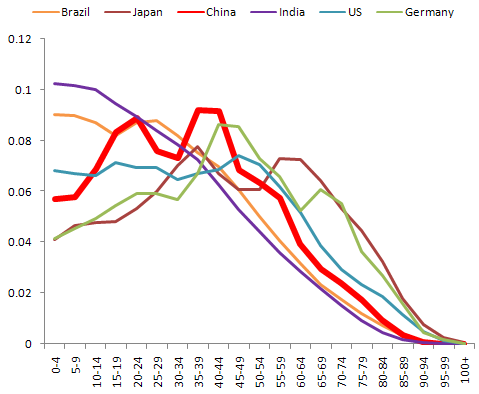

Here are the age structures of some major countries, young and old:

Vertical axis indicates the fraction of the population that resides in each age category.

Germany and Japan have the pig-in-the-python shape that results from falling birthrates. The US has a flatter age structure, presumably due to a combination of births and immigration. Brazil and India have very young populations, with the mode at the left hand side. Given the delay between birth and fertility, that builds in a lot of future growth.

Compared to Germany and Japan, China hardly seems to be on the verge of an aging crisis. In any case, given the bathtub delay between birth and maturity, a baby boom wouldn’t improve the dependency ratio for almost two decades.

More importantly, growth is not a sustainable strategy for coping with aging. At the same time that growth augments labor, it dilutes the resource base and capital available per capita. If you believe that people are the ultimate resource, i.e. that increasing returns to human capital will create offsetting technical opportunities, that might work. I rather doubt that’s a viable strategy though; human capital is more than just warm bodies (of which there’s no shortage); it’s educated and productive bodies – which are harder to get. More likely, a growth strategy just accelerates the arrival of resource constraints. In any case, the population growth play is not robust to uncertainty about future returns to human capital – if there are bumps on the technical road, it’s disastrous.

To say that population growth is a bad strategy for China is not necessarily to say that the one child policy should stay. If its enforcement is spotty, perhaps lifting it would be a good thing. Focusing on incentives and values that internalize population tradeoffs might lead to a better long term outcome than top-down control.

On the other hand, it’s not clear whether or not people in China would start having more children were the One Child Policy to be lifted; fertility does seem to decline with education and income, so population growth would be kept under check.

This is a more politically inclined argument than yours but, even considering (as I do) people as the Ultimate Resource, able to offset partially the Limits to Growth by creating other types of capital, the response to ageing is clearly not indefinite population growth. We have more and more elder people, and fortunately they are also healthier than before. Increasing retirement age, while deeply unpopular with everyone involved, is clearly a way forward. If people live longer and healthier lives, they will have to work longer. Allowing immigration to fill the gaps – another deeply unpopular concept… – is the other way forward.

The fact that the two more clear measures are both so unpopular is something we’ll have to start dealing with very quickly.

Good points. I meant to convey the first in my closing, but somehow lost the thought.

I think raising the retirement age is essential. To some extent, that’s bound up with other things that need to happen, like a stronger approach to life-long learning, less adversarial labor-management relations, and separation of health care from work.

I think we have a lot of unpopular measures ahead, unfortunately.

The three remaining point you mention – stronger approach to life-long learning, less adversarial labour-management relations and separation of health care from work – are indeed important points, although you hardly ever listen to them mentioned in this context. The third is taken for granted here in Europe anyway, and the other two are at least less unpopular then raising the retirement age or the increase of immigration. We’ll need all of it, I guess.

Carlos, based on my observations in China, if the one-child policy is lifted, people will definitely start having more children, especially in the rural areas. As you might know, the largely uneducated rural population still makes up the majority in China.

I don’t necessarily like the one-child policy, but I think some sort of population control measure is needed in China.

Tom, your age structure graph is so interesting! I’ve Twitted your post. Do you have a Twitter account that I can follow?

Xujun, what is the situation in rural areas? Aren’t there parts of the country where people are already allowed to have more than one child?

The degree of the policy enforcement is uneven throughout China’s rural areas. (It is more homogeneous in the cities.) Even though the enforcement was often lax in some parts of the countryside, in the past many of the families that violated the policy had to pay fines, or go into hiding until the baby was born. Given the farmers’ tendency to have many children per family, I’m sure without the one-child policy the rural population growth rate would have been much higher.