I’m working on a unified minicourse in stats for SD. A first spinoff is an update of my Bathtub Statistics model.

Asides

Modeling at the speed of BS

I’ve been involved in some debates over legislation here in Montana recently. I think there’s a solid rational case against a couple of bills, but it turns out not to matter, because the supporters have one tool the opponents lack: they’re willing to make stuff up. No amount of reason can overwhelm a carefully-crafted fabrication handed to a motivated listener.

One aspect of this is a consumer problem. If I worked with someone who told me a nice little story about their public doings, and then I was presented with court documents explicitly contradicting their account, they would quickly feel the sole of my boot on their backside. But it seems that some legislators simply don’t care, so long as the story aligns with their predispositions.

But I think the bigger problem is that BS is simply faster and cheaper than the truth. Getting to truth with models is slow, expensive and sometimes elusive. Making stuff up is comparatively easy, and you never have to worry about being wrong (because you don’t care). AI doesn’t help, because it accelerates fabrication and hallucination more than it helps real modeling.

At the moment, there are at least 3 areas where I have considerable experience, working models, and a desire to see policy improve. But I’m finding it hard to contribute, because debates over these issues are exclusively tribal. I fear this is the onset of a new dark age, where oligarchy and the one party state overwhelm the emerging tools we enjoy.

Just Say No to Complex Equations

Found in an old version of a project model:

IF THEN ELSE( First Time Work Flow[i,Proj,stage

] * TIME STEP >= ( Perceived First Time Scope UEC Work

[i,Proj,uec] + Unstarted Work[i,Proj,stage] )

:OR: Task Is Active[i,Proj,Workstage] = 0

:OR: avg density of OOS work[i,Proj,stage] > OOS density threshold,

Completed work still out of sequence[i,Proj,stage] / TIME STEP

+ new work out of sequence[i,Proj,stage] ,

MIN( Completed work still out of sequence[i,Proj,stage] / Minimum Time to Retrofit Prerequisites into OOS Work

+ new work out of sequence[i,Proj,stage],

new work in sequence[i,Proj,stage]

* ZIDZ( avg density of OOS work[i,Proj,stage],

1 – avg density of OOS work[i,Proj,stage] ) ) )

An equation like this needs to be broken into at least 3 or 4 human-readable chunks. In reviewing papers for the SD conference, I see similar constructions more often than I’d like.

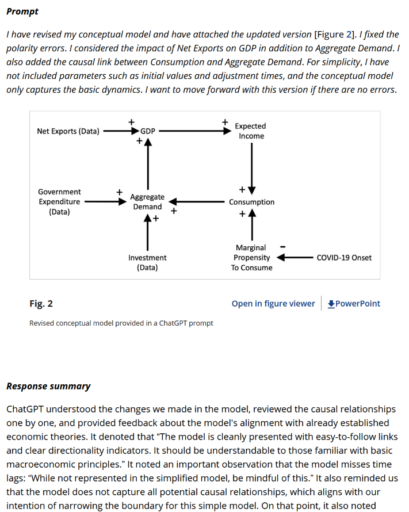

AI for modeling – what (not) to do

Generative AI and simulation modeling: how should you (not) use large language models like ChatGPT

Ali Akhavan, Mohammad S. Jalali

Abstract

Generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) tools, such as Large Language Models (LLMs) and chatbots like ChatGPT, hold promise for advancing simulation modeling. Despite their growing prominence and associated debates, there remains a gap in comprehending the potential of generative AI in this field and a lack of guidelines for its effective deployment. This article endeavors to bridge these gaps. We discuss the applications of ChatGPT through an example of modeling COVID-19’s impact on economic growth in the United States. However, our guidelines are generic and can be applied to a broader range of generative AI tools. Our work presents a systematic approach for integrating generative AI across the simulation research continuum, from problem articulation to insight derivation and documentation, independent of the specific simulation modeling method. We emphasize while these tools offer enhancements in refining ideas and expediting processes, they should complement rather than replace critical thinking inherent to research.

It’s loaded with useful examples of prompts and responses:

I haven’t really digested this yet, but I’m looking forward to writing about it. In the meantime, I’m very interested to hear your take in the comments.

Defining SD

Open Access Note by Asmeret Naugle, Saeed Langarudi, Timothy Clancy: https://doi.org/10.1002/sdr.1762

Abstract

A clear definition of system dynamics modeling can provide shared understanding and clarify the impact of the field. We introduce a set of characteristics that define quantitative system dynamics, selected to capture core philosophy, describe theoretical and practical principles, and apply to historical work but be flexible enough to remain relevant as the field progresses. The defining characteristics are: (1) models are based on causal feedback structure, (2) accumulations and delays are foundational, (3) models are equation-based, (4) concept of time is continuous, and (5) analysis focuses on feedback dynamics. We discuss the implications of these principles and use them to identify research opportunities in which the system dynamics field can advance. These research opportunities include causality, disaggregation, data science and AI, and contributing to scientific advancement. Progress in these areas has the potential to improve both the science and practice of system dynamics.

I shared some earlier thoughts here, but my refined view is in the SDR now:

Invited Commentaries by Tom Fiddaman, Josephine Kaviti Musango, Markus Schwaninger, Miriam Spano: https://doi.org/10.1002/sdr.1763

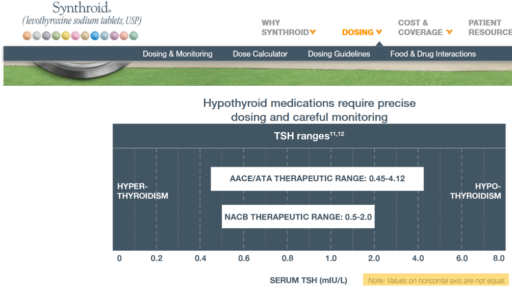

Thyroid Dynamics: Chartjunk

I just ran across a funny instance of TSH nonlinearity. Check out the axis on this chart:

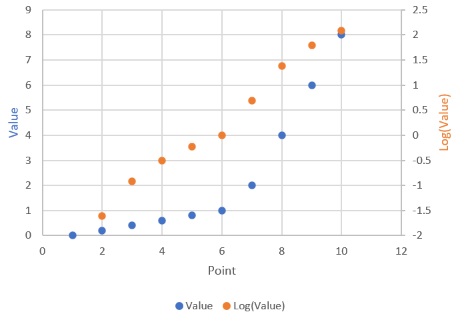

It’s actually not as bad as you’d think: the irregular axis is actually a decent approximation of a log-linear scale:

It’s actually not as bad as you’d think: the irregular axis is actually a decent approximation of a log-linear scale:

My main gripe is that the perceptual midpoint of the ATA range bar on the chart is roughly 0.9, whereas the true logarithmic midpoint is more like 1.6. The NACB bar is similarly distorted.

My main gripe is that the perceptual midpoint of the ATA range bar on the chart is roughly 0.9, whereas the true logarithmic midpoint is more like 1.6. The NACB bar is similarly distorted.

Planaria for nonlinear dynamic behavioral simulation, unite!

Check Your Units, 2023 Edition

A Corgi-sized meteor as heavy as 4 baby elephants hit Texas, eh? Is energy equivalent the same as weight? Are animal meteors meatier? So many questions …

Spreadsheets Strike Again

In this BBC podcast, stand-up mathematician Matt Parker explains the latest big spreadsheet screwup: overstating European productivity growth.

There are a bunch of killers in spreadsheets, but in this case the culprit was lack of a time axis concept, making it easy to misalign times for the GDP and labor variables. The interesting thing is that a spreadsheet’s strong suite – visibility of the numbers – didn’t help. Someone should have seen 22% productivity growth and thought, “that’s bonkers” – but perhaps expectations of a COVID19 rebound short-circuited the mental reality check.

Believing Exponential Growth

Verghese: You were prescient about the shape of the BA.5 variant and how that might look a couple of months before we saw it. What does your crystal ball show of what we can expect in the United Kingdom and the United States in terms of variants that have not yet emerged?

Pagel: The other thing that strikes me is that people still haven’t understood exponential growth 2.5 years in. With the BA.5 or BA.3 before it, or the first Omicron before that, people say, oh, how did you know? Well, it was doubling every week, and I projected forward. Then in 8 weeks, it’s dominant.

It’s not that hard. It’s just that people don’t believe it. Somehow people think, oh, well, it can’t happen. But what exactly is going to stop it? You have to have a mechanism to stop exponential growth at the moment when enough people have immunity. The moment doesn’t last very long, and then you get these repeated waves.

You have to have a mechanism that will stop it evolving, and I don’t see that. We’re not doing anything different to what we were doing a year ago or 6 months ago. So yes, it’s still evolving. There are still new variants shooting up all the time.

At the moment, none of these look devastating; we probably have at least 6 weeks’ breathing space. But another variant will come because I can’t see that we’re doing anything to stop it.