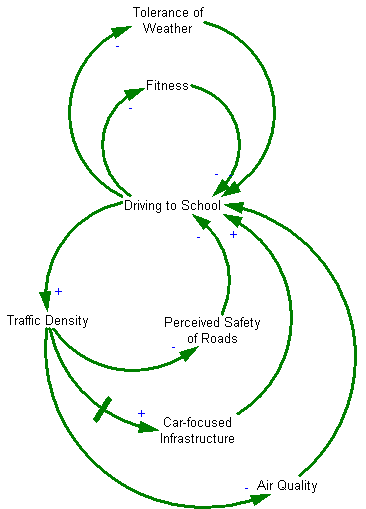

A nice reflection on modeling in emotionally charged situations, from Drew Jones, Don Seville & Donella Meadows, Resource Sustainability in Commodity Systems: The Sawmill Industry in the Northern Forest:

Through the workshops and discussions about the forest economy, we also learned that even raising questions of growth and limits can trigger strong defensive routines …, both at the individual level and the organizational level, that make it difficult even to remain engaged in thinking about ecological limits and, therefore, taking any action. Managing these complex process challenges effectively was essential to using systems modeling to help people move towards well-reasoned action or inaction.

… We were presenting our base run to a group of mill executives and landowners from five different companies. During the walk-through of the base-run behavior of mill capacity (which begins to contract severely several decades in the future) we found that a few participants quickly dismissed that possibility, saying, ‘‘Sawmill capacity in this region will never shrink like that,’’ and aggressively pressing us on what factors we had included so that (we presume) they could uncover something missing or incorrect and dismiss the findings. Their body language and tone of voice led us to believe the participants were angry and emotionally charged.

… we came to identify a recurring set of defensive routines, that is, both emotionally laden reflexive responses to seeing the graphs of overshoot in which participants did not connect their critique to an underlying structural theory, or simply disengaged from thinking about the questions at hand. … When we encountered these reactions, we found ourselves torn between avoiding the conflict (the ‘‘flight’’ reaction; modifying our story to fit within their pre-existing assumptions, de-emphasizing the behavior of the model and switching to interview mode, talking about the systems methodology rather than implications of this particular model) or by pushing harder on our own viewpoint (the ‘‘fight’’ reaction; explaining why our assumptions are right, defending the logic behind our model). Neither of these responses was effective.

Back to the presentation to the industry group. During a break, after we had just survived the morning’s tensions and had struggled to avoid ‘‘fight or flight,’’ Dana [Meadows] walked up to us, smiling, and said, ‘‘Isn’t this going great?’’ ‘‘What?!?,’’ we thought.

‘‘The main purpose of our modeling,’’ she said ‘‘is to bring people to this moment—the moment of discomfort, of cognitive dissonance, where they can begin to see how current ways of thinking and their deeply held beliefs are not working anymore, how they are creating a future that they don’t want. The key as a modeler who triggers denial or apathy is to bring the group to this moment, and then just breathe. Hold us there for as long as possible. Don’t fight back. Don’t qualify your conclusions about what structures create what behaviors. State them clearly, and then just hold on.’’