The Fortress World scenario came up in Bert de Vries’ presentation at the Balaton meeting today. It’s a dystopian global future in which the rich retreat into safe havens (a macro version of gated communities) while the rest of the world degenerates into some combination of feudal subsistence, resource extraction and chaos.

On dark days, looks increasingly to me like this is already playing out in the US with the disappearance of the middle class.

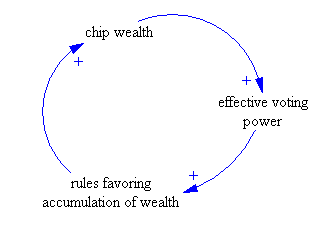

The drivers of rising inequity in the US seem fairly simple. With globalization, capital has become mobile while labor remains tied to geography. So, capital investment flees high wage countries (US) and jobs follow. Asset income goes up, because capital is leveraged by cheaper labor and has good bargaining power among hungry host countries. There’s downward pressure on rich world wages, because with less capital per capita employed, the marginal productivity of labor is lower.

It’s not all bad for the rich world working class, because cheaper goods (WalMart) offset wage losses to some degree. If asset and wage income were uniformly distributed, there might even be a net benefit.

However, asset income and wages aren’t uniformly distributed, so income disparity goes up. Pre-globalization, this wasn’t so noticeable, because there was an implicit deal, in which wage earners knew that, even if they didn’t own all the capital in their country, at least they’d be the beneficiaries of it in some sense through employment and trickle down. Free trade and mobile capital turns the deal into a divorce, which puts a sharp point on questions of property rights allocations that were never quite fair, and sows the seeds of future discontent among the losers.

So far, everyone appears to be committed to pursuing this thread to its logical conclusion. Probably most are unwitting participants; workers are as enthusiastic about offshoring of capital in their pension funds as are the captains of industry.

However, it seems to me that there are several corrosive effects. The asset-owning rich appear convinced that their windfall has arrived because they’re smart, that the misfortunes of the masses are due to laziness. Their incentive to invest in services like education for labor they don’t need is no longer palpable. Uneducated masses are easier to manipulate anyway. Meanwhile the masses are desperate (if misguided) to lower tax burdens in order to compete with offshore labor.

The ultimate effect seems likely to hollow out the human capital of the rich world, leaving only tycoons and serfs, with perhaps a few protected sectors of the economy (pilots for tycoons’ jets). But is that a plausible end-state for this game?

If I were an American tycoon endowed with a little enlightened self interest, I’d be worried about several ways things could go wrong:

- Increasing income disparity and loss of human capital cause a loss of civility at home, requiring wealthy enclaves to become desperate armed camps.

- Political turbulence abroad leads to loss of control of all that capital that went overseas.

- The global economy reaches such a vast physical scale that no amount of personal wealth provides adequate insulation against its side effects.

These outcomes could be triggered or amplified by financial or ecological stress. Even if you don’t care about equity or social justice per se, these possibilities seem like a great reason to invest in human and social capital at home and abroad.

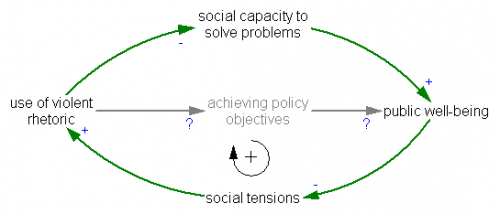

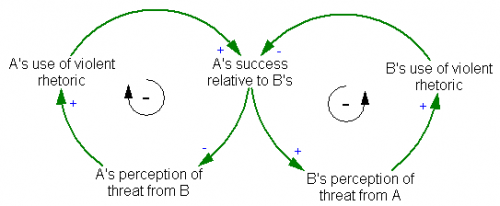

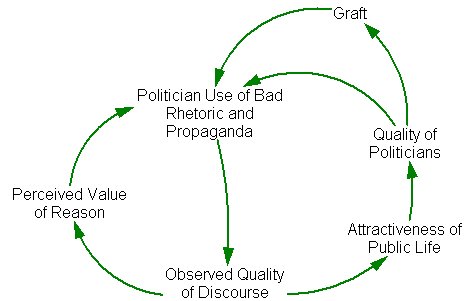

In the escalation archetype, two sides struggle to maintain an advantage over each other. This creates two inner negative feedback loops, which together create a positive feedback loop (a figure-8 around the two negative loops). It’s interesting to note that, so far, the use of violent rhetoric is fairly one-sided – the escalation is happening within the political right (candidates vying for attention?) more than between left and right.

In the escalation archetype, two sides struggle to maintain an advantage over each other. This creates two inner negative feedback loops, which together create a positive feedback loop (a figure-8 around the two negative loops). It’s interesting to note that, so far, the use of violent rhetoric is fairly one-sided – the escalation is happening within the political right (candidates vying for attention?) more than between left and right. The positive feedbacks around violent rhetoric create a societal trap, from which it may be difficult to extricate ourselves. If there’s a general systems insight about vicious cycles, it’s that the best policy is prevention – just don’t start down that road (if you doubt this, play the

The positive feedbacks around violent rhetoric create a societal trap, from which it may be difficult to extricate ourselves. If there’s a general systems insight about vicious cycles, it’s that the best policy is prevention – just don’t start down that road (if you doubt this, play the