No? So why do we let lawyers design control systems for our economic and social systems, without much input from people trained in dynamic systems?

Category: Policy

Greenwash labeling

I like green labeling, but I’m not convinced that, by itself, it’s theoretically a viable way to get the economy to a good environmental endpoint. In practice, it’s probably even worse. Consider Energy Star. It’s supposed to be “helping us all save money and protect the environment through energy efficient products and practices.” The reality is that it gives low-quality information a veneer of authenticity, misleading consumers. I have no doubt that it has some benefits, especially through technology forcing, but it’s soooo much less than it could be.

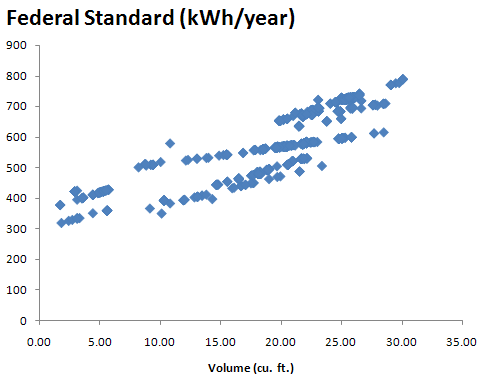

The fundamental signal Energy Star sends is flawed. Because it categorizes appliances by size and type, a hog gets a star as long as it’s also big and of less-efficient design (like a side-by-side refrigerator/freezer). Here’s the size-energy relationship of the federal energy performance standard (which Energy Star fridges must exceed by 20%):

Notice that the standard for a 20 cubic foot fridge is anywhere from 470 to 660 kWh/year.

When rebates go bad

There’s a long-standing argument over the extent to which rebound effects eat up the gains of energy-conserving technologies, and whether energy conservation programs are efficient. I don’t generally side with the hardline economists who argue that conservation programs fail a cost benefit test, because I think there really are some $20 bills scattered about, waiting to be harvested by an intelligent mix of information and incentives. At the same time, some rebate and credit programs look pretty fishy to me.

On the plus side, I just bought a new refrigerator, using Montana’s $100 stimulus credit. There’s no rebound, because I have to hand over the old one for recycling. There is some rebound potential in general, because I could have used the $100 to upgrade to a larger model. Energy Star segments the market, so a big side-by-side fridge can pass while consuming more energy than a little top-freezer. That’s just stupid. Fortunately, most people have space constraints, so the short run price elasticity of fridge size is low.

On the minus side, consider tax credits for hybrid vehicles. For a super-efficient Prius or Insight, I can sort of see the point. But a $2600 credit for a Toyota Highlander getting 26mpg? What a joke! Mercifully that foolishness has been phased out. But there’s plenty more where that came from.

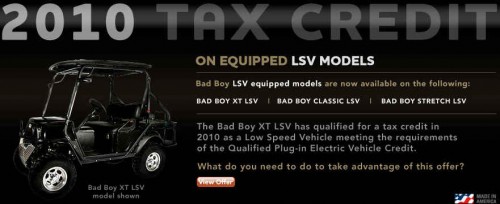

Consider this Bad Boy:

The Zero-Emission Agricultural Utility Terrain Vehicle (Agricultural UTV) Rebate Program will credit $1950 in the hope of fostering greener farms. But this firm knows who it’s really marketing to:

Is there really good control over the use of the $, or is public funding just mechanizing outdoor activities where people ought to use the original low-emissions vehicle, their feet? When will I get a rebate for my horse?

States' role in climate policy

Jack Dirmann passed along an interesting paper arguing for a bigger role for states in setting federal climate policy.

This article explains why states and localities need to be full partners in a national climate change effort based on federal legislation or the existing Clean Air Act. A large share of reductions with the lowest cost and the greatest co-benefits (e.g., job creation, technology development, reduction of other pollutants) are in areas that a federal cap-and-trade program or other purely federal measures will not easily reach. These are also areas where the states have traditionally exercised their powers – including land use, building construction, transportation, and recycling. The economic recovery and expansion will require direct state and local management of climate and energy actions to reach full potential and efficiency.

This article also describes in detail a proposed state climate action planning process that would help make the states full partners. This state planning process – based on a proven template from actions taken by many states – provides an opportunity to achieve cheaper, faster, and greater emissions reductions than federal legislation or regulation alone would achieve. It would also realize macroeconomic benefits and non-economic co-benefits, and would mean that the national program is more economically and environmentally sustainable.

Climate Science, Climate Policy and Montana

Last night I gave a climate talk at the Museum of the Rockies here in Bozeman, organized by Cherilyn DeVries and sponsored by United Methodist. It was a lot of fun – we had a terrific discussion at the end, and the museum’s monster projector was addictive for running C-LEARN live. Thanks to everyone who helped to make it happen. My next challenge is to do this for young kids.

My slides are here as a PowerPoint show: Climate Science, Climate Policy & Montana (better because it includes some animated builds) or PDF: Climate Science, Climate Policy & Montana (PDF)

Some related resources:

Climate Interactive & the online C-LEARN model

Montana Climate Change Advisory Committee

Montana emissions inventory & forecast visualization (click through the graphic):

The real Kerry-Lieberman APA stands up, with two big surprises

The official discussion draft of the Kerry-Lieberman American Power Act is out. My heart sank when I saw the page count – 987. I won’t be able to review this in any detail soon. Based on a quick look, I see two potentially huge items: the “hard price collar” has a soft ceiling, and transport fuels are in the market, despite claims to the contrary.

Hard is soft

First, the summary states that there’s a “hard price collar which binds carbon prices and creates a predictable system for carbon prices to rise at a fixed rate over inflation.” That’s not quite right. There is indeed a floor, set by an auction reserve price in Section 790. However, I can’t find a ceiling as such. Instead, Section 726 establishes a “Cost Containment Reserve” that is somewhat like the Waxman-Markey strategic reserve, without the roach motel moving average price (offsets check in, but they don’t check out). Instead, reserve allowances are available at the escalating ceiling price ($25 + 5%/yr). There’s a much larger initial reserve (4 gigatons) and I think a more generous topping off (1.5% of allowances each year initially; 5% after 2030). However, there appears to be no mechanism to provide allowances beyond the set-aside. That means that the economy-wide target is in fact binding. If demand eats up the reserve allowance buffer, prices will have to rise above the ceiling in order to clear the market. So, the market actually faces a hard target, with the reserve/ceiling mechanism merely creating a temporary respite from price spikes. The price ceiling is soft if allowance demand at the ceiling price is sufficient to exhaust the buffer. The mental model behind this design must be that estimated future emission prices are about right, so that one need only protect against short term volatility. However, if those estimates are systematically wrong, and the marginal cost of mitigation persistently exceeds the ceiling, the reserve provides no protection against price escalation.

Transport is in the market

The short transport summary asserts:

Since a robust domestic refining industry is critical to our national security, we needed to make a change. We took fuel providers out of the market. Instead of every refinery participating in the market for allowances, we made sure the price of carbon was constant across the industry. That means all fuel providers see the same price of carbon in a given quarter. The system is simple. First, the EPA and EIA Administrators look to historic product sales to estimate how many allowances will be necessary to cover emissions for the quarter, and they set that number of allowances aside at the market price. Then refineries and fuel providers sell fuel, competing as they have always done to offer the best product at the best price. Finally, at the end of the quarter, the refiners and fuel providers purchase the allowances that have been set aside for them. If there are too many or too few allowances set aside, that difference is made up by adjusting the projection for the following quarter. These allowances cannot be banked or traded, and can only be used for compliance purposes.

In fact, transport is in the market, just via a different mechanism. Instead of buying allowances realtime, with banking and borrowing, refiners are price takers and get allowances via a set-aside mechanism. Since there’s nothing about the mechanism that creates allowances, the market still has to clear. The mechanism simply introduces a one quarter delay into the market clearing process. I don’t see how this additional complication is any better for refiners. Introducing the delay into the negative feedback loops that clear the market could be destabilizing. This is so enticing, I’ll have to simulate it.

My analysis is a bit hasty here, so I could be wrong, but if I’m right these two issues have huge implications for the performance of the bill.

Kerry-Lieberman "American Power Act" leaked

I think it’s a second-best policy, but perhaps the most we can hope for, and better than nothing.

Climate Progress has a first analysis and links to the leaked draft legislation outline and short summary of the Kerry-Lieberman American Power Act. [Update: there’s now a nice summary table.] For me, the bottom line is, what are the emissions and price trajectories, what emissions are covered, and where does the money go?

The target is 95.25% of 2005 by 2013, 83% by 2020, 58% by 2030, and 17% by 2050, with six Kyoto gases covered. Entities over 25 MTCO2eq/year are covered. Sector coverage is unclear; the summary refers to “the three major emitting sectors, power plants, heavy industry, and transportation” which is actually a rather incomplete list. Presumably the implication is that a lot of residential, commercial, and manufacturing emissions get picked up upstream, but the mechanics aren’t clear.

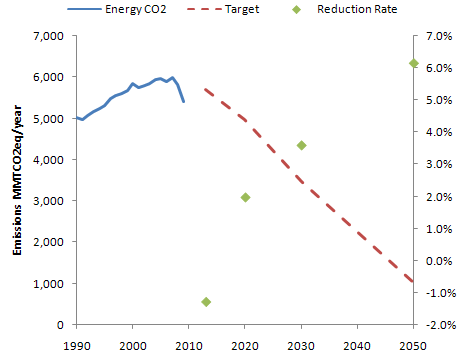

The target looks like this [Update: ignoring minor gases]:

This is not much different from ACES or CLEAR, and like them it’s backwards. Emissions reductions are back-loaded. The rate of reduction (green dots) from 2030 to 2050, 6.1%/year, is hardly plausible without massive retrofit or abandonment of existing capital (or negative economic growth). Given that the easiest reductions are likely to be the first, not the last, more aggressive action should be happening up front. (Actually there are a multitude of reasons for front-loading reductions as much as reasonable price stability allows).

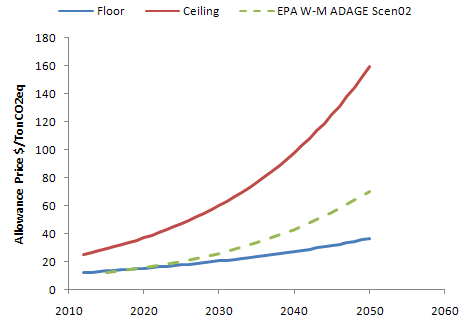

There’s also a price collar:

These mechanisms provide a predictable price corridor, with the expected prices of the EPA Waxman-Markey analysis (dashed green) running right up the middle. The silly strategic reserve is gone. Still, I think this arrangement is backwards, in a different sense from the target. The right way to manage the uncertainty in the long run emissions trajectory needed to stabilize climate without triggering short run economic dislocation is with a mechanism that yields stable prices over the short to medium term, while providing for adaptive adjustment of the long term price trajectory to achieve emissions stability. A cap and trade with no safety valve is essentially the opposite of that: short run volatility with long run rigidity, and therefore a poor choice. The price collar bounds the short term volatility to 2:1 (early) to 4:1 (late) price movements, but it doesn’t do anything to provide for adaptation of the emissions target or price collar if emissions reductions turn out to be unexpectedly hard, easy, important, etc. It’s likely that the target and collar will be regarded as property rights and hard to change later in the game.

I think we should expect the unexpected. My personal guess is that the EPA allowance price estimates are way too low. In that case, we’ll find ourselves stuck on the price ceiling, with targets unmet. 83% reductions in emissions at an emissions price corresponding with under $1/gallon for fuel just strike me as unlikely, unless we’re very lucky technologically. My preference would be an adaptive carbon price, starting at a substantially higher level (high enough to prevent investment in new carbon intensive capital, but not so high initially as to strand those assets – maybe $50/TonCO2). By default, the price should rise at some modest rate, with an explicit adjustment process taking place at longish intervals so that new information can be incorporated. Essentially the goal is to implement feedback control that stabilizes long term climate without short term volatility (as here or here and here).

Some other gut reactions:

Good:

- Clean energy R&D funding.

- Allowance distribution by auction.

- Border adjustments (I can only find these in the summary, not the draft outline).

Bad:

- More subsidies, guarantees and other support for nuclear power plants. Why not let the first round play out first? Is this really a good use of resources or a level playing field?

- Subsidized CCS deployment. There are good reasons for subsidizing R&D, but deployment should be primarily motivated by the economic incentive of the emissions price.

- Other deployment incentives. Let the price do the work!

- Rebates through utilities. There’s good evidence that total bills are more salient to consumers than marginal costs, so this at least partially defeats the price signal. At least it’s temporary (though transient measures have a way of becoming entitlements).

Indifferent:

- Preemption of state cap & trade schemes. Sorry, RGGI, AB32, and WCI. This probably has to happen.

- Green jobs claims. In the long run, employment is controlled by a bunch of negative feedback loops, so it’s not likely to change a lot. The current effects of the housing bust/financial crisis and eventual effects of big twin deficits are likely to overwhelm any climate policy signal. The real issue is how to create wealth without borrowing it from the future (e.g., by filling up the atmospheric bathtub with GHGs) and sustaining vulnerability to oil shocks, and on that score this is a good move.

- State preemption of offshore oil leasing within 75 miles of its shoreline. Is this anything more than an illusion of protection?

- Banking, borrowing and offsets allowed.

Unclear:

- Performance standards for coal plants.

- Transportation efficiency measures.

- Industry rebates to prevent leakage (does this defeat the price signal?).

Copenhagen – the breaking point

Der Spiegel has obtained audio of the heads of state negotiating in the final hours of COP15. Its fascinating stuff. The headline reads, How China and India Sabotaged the UN Climate Summit. This point was actually raised back in December by Mark Lynas at the Guardian (there’s a nice discussion and event timeline at Inside-Out China). On the surface the video supports the view that China and India were the material obstacle to agreement on a -50% by 2050 target. However, I think it’s still hard to make attributions about motive. We don’t know, for example, whether China is opposed because it anticipates raising emissions to levels that would make 50% cuts physically impossible, or because it sees the discussion of cuts as fundamentally linked to the unaddressed question of responsibility, as hinted by He Yafei near the end of the video. Was the absence of Wen Jiabao obstruction or a defensive tactic? We have even less information about India, merely that it objected to “prejudging options,” whatever that means.

What the headline omits is the observation in the final pages of the article, that the de facto US position may not have been so different from China’s:

Part 3: Obama Stabs the Europeans in the Back

…

But then Obama stabbed the Europeans in the back, saying that it would be best to shelve the concrete reduction targets for the time being. “We will try to give some opportunities for its resolution outside of this multilateral setting … And I am saying that, confident that, I think China still is as desirous of an agreement, as we are.”

‘Other Business to Attend To’

At the end of his little speech, which lasted 3 minutes and 42 seconds, Obama even downplayed the importance of the climate conference, saying “Nicolas, we are not staying until tomorrow. I’m just letting you know. Because all of us obviously have extraordinarily important other business to attend to.”

Some in the room felt queasy. Exactly which side was Obama on? He couldn’t score any domestic political points with the climate issue. The general consensus was that he was unwilling to make any legally binding commitments, because they would be used against him in the US Congress. Was he merely interested in leaving Copenhagen looking like an assertive statesman?

It was now clear that Obama and the Chinese were in fact in the same boat, and that the Europeans were about to drown.

This article and video almost makes up for Spiegel’s terrible coverage of the climate email debacle.

Related analysis of developed-developing emissions trajectories:

Stop talking, start studying?

Roger Pielke Jr. poses a carbon price paradox:

The carbon price paradox is that any politically conceivable price on carbon can do little more than have a marginal effect on the modern energy economy. A price that would be high enough to induce transformational change is just not in the cards. Thus, carbon pricing alone cannot lead to a transformation of the energy economy.

Advocates for a response to climate change based on increasing the costs of carbon-based energy skate around the fact that people react very negatively to higher prices by promising that action won’t really cost that much. … If action on climate change is indeed “not costly” then it would logically follow the only reasons for anyone to question a strategy based on increasing the costs of energy are complete ignorance and/or a crass willingness to destroy the planet for private gain. … There is another view. Specifically that the current ranges of actions at the forefront of the climate debate focused on putting a price on carbon in order to motivate action are misguided and cannot succeed. This argument goes as follows: In order for action to occur costs must be significant enough to change incentives and thus behavior. Without the sugarcoating, pricing carbon (whether via cap-and-trade or a direct tax) is designed to be costly. In this basic principle lies the seed of failure. Policy makers will do (and have done) everything they can to avoid imposing higher costs of energy on their constituents via dodgy offsets, overly generous allowances, safety valves, hot air, and whatever other gimmick they can come up with.

His prescription (and that of the Breakthrough Institute) is low carbon taxes, reinvested in R&D:

We believe that soon-to-be-president Obama’s proposal to spend $150 billion over the next 10 years on developing carbon-free energy technologies and infrastructure is the right first step. … a $5 charge on each ton of carbon dioxide produced in the use of fossil fuel energy would raise $30 billion a year. This is more than enough to finance the Obama plan twice over.

… We would like to create the conditions for a virtuous cycle, whereby a small, politically acceptable charge for the use of carbon emitting energy, is used to invest immediately in the development and subsequent deployment of technologies that will accelerate the decarbonization of the U.S. economy.

…

Stop talking, start solving

As the nation begins to rely less and less on fossil fuels, the political atmosphere will be more favorable to gradually raising the charge on carbon, as it will have less of an impact on businesses and consumers, this in turn will ensure that there is a steady, perhaps even growing source of funds to support a process of continuous technological innovation.

This approach reminds me of an old joke:

Lenin, Stalin, Khrushchev and Brezhnev are travelling together on a train. Unexpectedly the train stops. Lenin suggests: “Perhaps, we should call a subbotnik, so that workers and peasants fix the problem.” Kruschev suggests rehabilitating the engineers, and leaves for a while, but nothing happens. Stalin, fed up, steps out to intervene. Rifle shots are heard, but when he returns there is still no motion. Brezhnev reaches over, pulls the curtain, and says, “Comrades, let’s pretend we’re moving.”

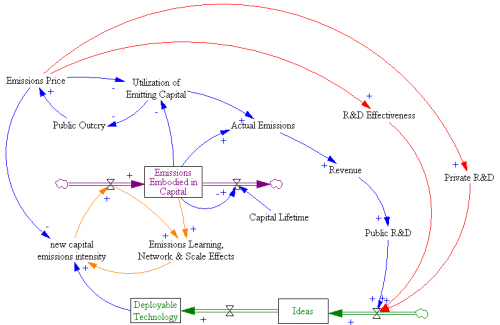

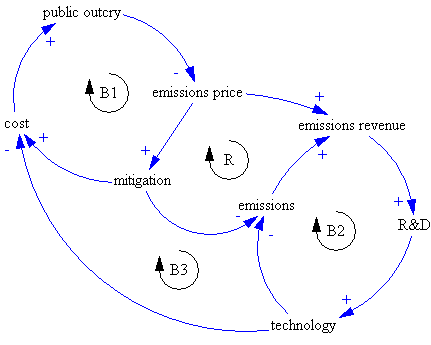

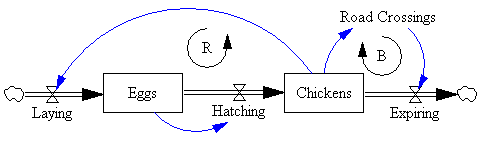

I translate the structure of Pielke’s argument like this:

Implementation of a high emissions price now would be undone politically (B1). A low emissions price triggers a virtuous cycle (R), as revenue reinvested in technology lowers the cost of future mitigation, minimizing public outcry and enabling the emissions price to go up. Note that this structure implies two other balancing loops (B2 & B3) that serve to weaken the R&D effect, because revenues fall as emissions fall.

If you elaborate on the diagram a bit, you can see why the technology-led strategy is unlikely to work:

First, there’s a huge delay between R&D investment and emergence of deployable technology (green stock-flow chain). R&D funded now by an emissions price could take decades to emerge. Second, there’s another huge delay from the slow turnover of the existing capital stock (purple) – even if we had cars that ran on water tomorrow, it would take 15 years or more to turn over the fleet. Buildings and infrastructure last much longer. Together, those delays greatly weaken the near-term effect of R&D on emissions, and therefore also prevent the virtuous cycle of reduced public outcry due to greater opportunities from getting going. As long as emissions prices remain low, the accumulation of commitments to high-emissions capital grows, increasing public resistance to a later change in direction. Continue reading “Stop talking, start studying?”

Are causal loop diagrams useful?

Reflecting on the Afghanistan counterinsurgency diagram in the NYTimes, Scott Johnson asked me whether I found causal loop diagrams (CLDs) to be useful. Some system dynamics hardliners don’t like them, and others use them routinely.

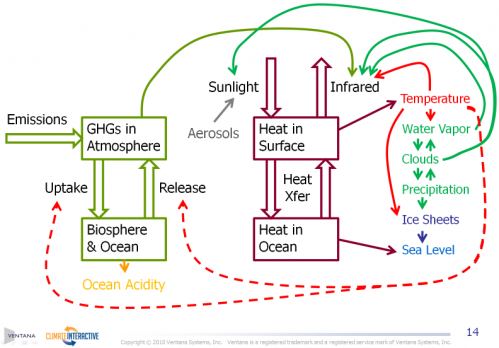

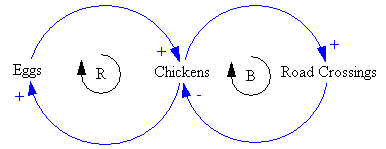

Here’s a CLD:

And here’s it’s stock-flow sibling:

My bottom line is:

- CLDs are very useful, if developed and presented with a little care.

- It’s often clearer to use a hybrid diagram that includes stock-flow “main chains”. However, that also involves a higher burden of explanation of the visual language.

- You can get into a lot of trouble if you try to mentally simulate the dynamics of a complex CLD, because they’re so underspecified (but you might be better off than talking, or making lists).

- You’re more likely to know what you’re talking about if you go through the process of building a model.

- A big, messy picture of a whole problem space can be a nice complement to a focused, high quality model.

Here’s why: