The blogosphere is filled with reports, originating in the Guardian, of developing countries’ fury over the leaked “Danish text” – a strawdog draft agreement.

The UN Copenhagen climate talks are in disarray today after developing countries reacted furiously to leaked documents that show world leaders will next week be asked to sign an agreement that hands more power to rich countries and sidelines the UN’s role in all future climate change negotiations.

The angry reaction strikes me as a missed opportunity. But more importantly, I think it’s a product of bad analysis, with an inflated population projection for the developing world creating a false impression of failure to achieve emissions convergence.

Here’s what I think is the essence of the text with respect to emissions trajectories:

3. Recalling the ultimate objective of the Convention, the Parties stress the urgency of action on both mitigation and adaptation and recognize the scientific view that the increase in global average temperature above pre-industrial levels ought not to exceed 2 degrees C. In this regard, the Parties:

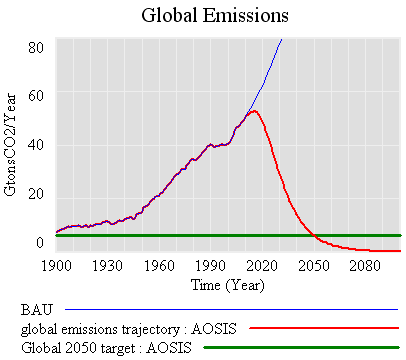

- Support the goal of a peak of global emissions as soon as possible, but no later than [2020], acknowledging that developed countries collectively have peaked and that the timeframe for peaking will be longer in developing countries,

- Support the goal of a reduction of global annual emissions in 2050 by at least 50 percent versus 1990 annual emissions, equivalent to at least 58 percent versus 2005 annual emissions. The Parties contributions towards the goal should take into account common but different responsibility and respective capabilities and a long term convergence of per capita emissions.

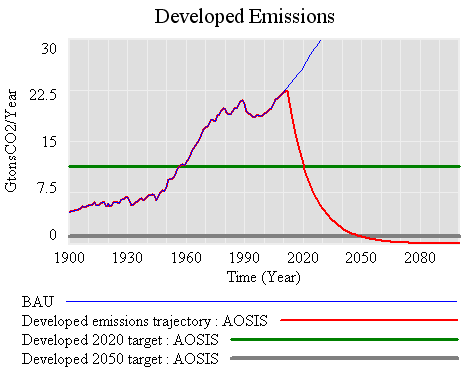

7. The developed country Parties commit to individual national economy wide targets for 2020. The targets in Attachment A would expect to yield aggregate emissions reductions by X1 percent by 2020 versus 1990 (X2 percent vs. 2005). The purchase of international offset credits will play a supplementary role to domestic action. The developed country Parties support a goal to reduce their emissions of greenhouse gases in aggregate by 80% or more by 2050 versus 1990 (X3 percent versus 2005).

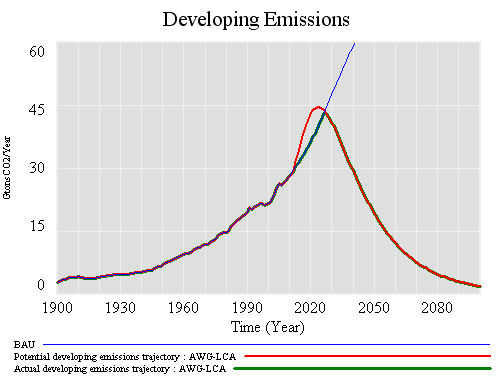

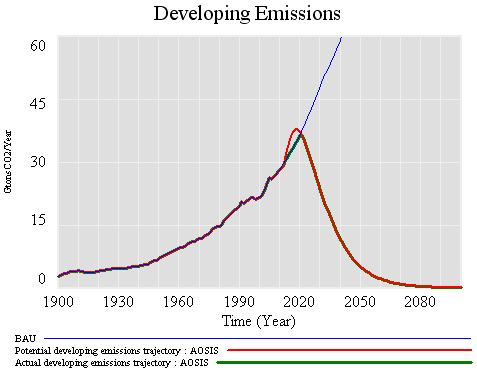

9. The developing country Parties, except the least developed countries which may contribute at their own discretion, commit to nationally appropriate mitigation actions, including actions supported and enabled by technology, financing and capacity-building. The developing countries’ individual mitigation action could in aggregate yield a [Y percent] deviation in [2020] from business as usual and yielding their collective emissions peak before [20XX] and decline thereafter.

These provisions are evidently the source of much of the outrage. Again from the Guardian:

A confidential analysis of the text by developing countries also seen by the Guardian shows deep unease over details of the text. In particular, it is understood to:

• Force developing countries to agree to specific emission cuts and measures that were not part of the original UN agreement;

…

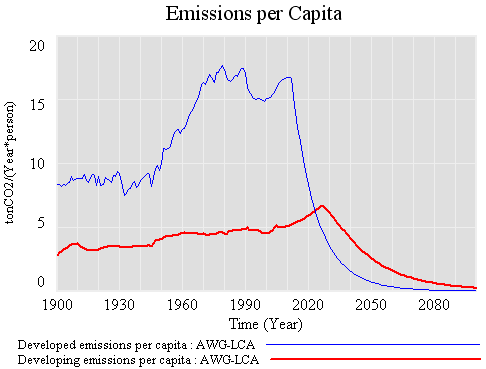

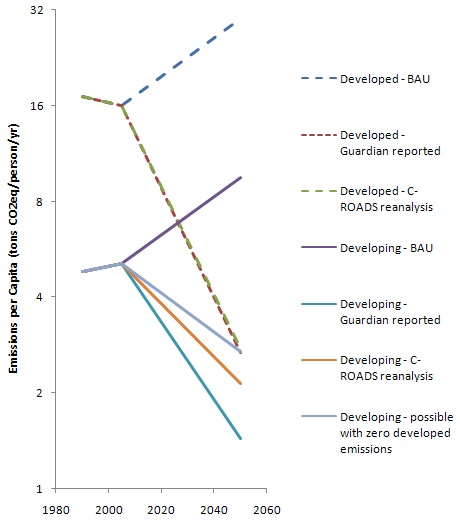

• Not allow poor countries to emit more than 1.44 tonnes of carbon per person by 2050, while allowing rich countries to emit 2.67 tonnes.

I have limited sympathy with the first point. If the world is to avoid the probability of serious climate change, emissions have to fall below natural uptake. That can’t happen if the developed world is shrinking while developing country emissions grow exponentially, so everyone has to play. You can’t cheat mother nature. If we’re serious about mitigation, the conversation has to be about how to help the developing countries peak and reduce, not whether they will.

The last point, concerning per capita emissions disparities, is actually not stated anywhere in the draft. Notice that the article 9 commitment for developing countries are expressed as variables to be filled in. To figure out what’s going on, I ran the numbers myself. I get about the same answer for the developed countries: 2.75 TonCO2eq/person/year. When multiplied by 1.5 billion people, that’s about 4.1 gigatons per year, leaving a budget of about 15.9 for the developing world (half of 1990 emissions of about 20 GtCO2eq, less 4.1). Dividing that by 1.44 yields an expected population in the developing world of 11 billion. That’s a bonkers population forecast, 2 billion above the UN high variant projection. If it came true, it would likely be a disaster in itself. More importantly, the per capita emissions ratios would be expressing a strange notion of (in)equity: the nearly 6 billion people added from 2005-2050 in the developing world would be emitting more than twice as much as all the people in the developing world.

If you rerun the numbers with a more sensible population forecast, with about 7.4 billion people in the developing world, the numbers are 2.75 and 2.15 tonsCO2eq/person/year in the developed and developing countries, respectively. (UN mid variant population projection is 7.9 billion, but I’m sticking with C-ROADS data for convenience, which has slightly different regional definitions). In other words, convergence is at hand: the world has gone from 3.5:1 emissions per cap in 1990 to 1.28:1 – a rather stunning achievement, not something to get mad about. In addition, it’s not physically possible to do much better than that for the developing world, because the developed world represents a small slice of the global population in 2050. For example, even if the developed world could reach zero emissions in 2050, the remaining emissions budget would only permit emissions of 2.7 tonsCO2eq/person/year in the developing countries.

Even if the high population projection came true, I still think it would be a mistake for developing countries to get mad, because there’s article 20:

20. The Parties share the view that the strengthened financial architecture should be able to handle gradually scaled up international public support. International public finance support to developing countries [should/shall] reach the order of [X] billion USD in 2020 on the basis of appropriate increases in mitigation and adaptation efforts by developing countries.

Rather than asking for higher emissions, developing countries could ask for a bigger [X] to compensate for smaller per capita emissions. Then they’d have help moving towards a low-carbon economy, with all the cobenefits that entails. They wouldn’t have to follow the developed world down a fossil-fired, energy intensive path that’s ultimately a dead end. Maybe the real anger arises from the difficulty of getting meaningful financial terms, but that’s the conversation we should be having if we want a shot at 2C or below.

Check my math. If you think I’m right, spread the word. It would be a shame if the possibility of a climate agreement were derailed by a flawed analysis of a draft document. If you think I’m wrong, please comment, and I’ll take another look.

Update: I’ve published the numbers behind this in my next post.