When times are tough, there are always calls to unravel environmental regulations and drill, baby, drill. I’m first in line to say that a lot of environmental regulation needs a paradigm shift, but this strikes me as a foolish hair-of-the-dog-that-bit-ya idea. Our current problems don’t come from regulation, and won’t be solved by deregulation.

On average, there’s no material deprivation in the US. We consume more petroleum per capita than any other large nation. Our problems are largely distributional – inequitable income distribution and, recently, high unemployment, which causes disproportionate harm to a few. Why solve a distributional problem by skewing environmental policy? This smacks of an attempt to grow out of our problems, which is surely doomed to the extent that growth relies on intensifying material throughput.

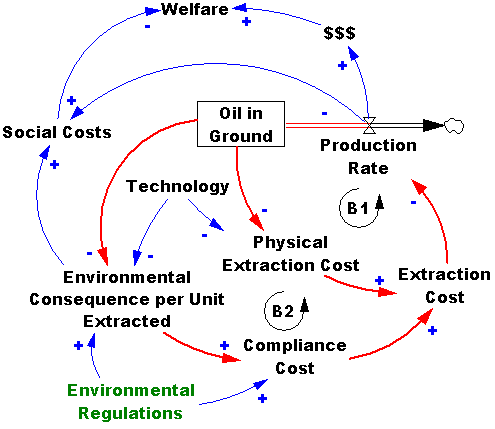

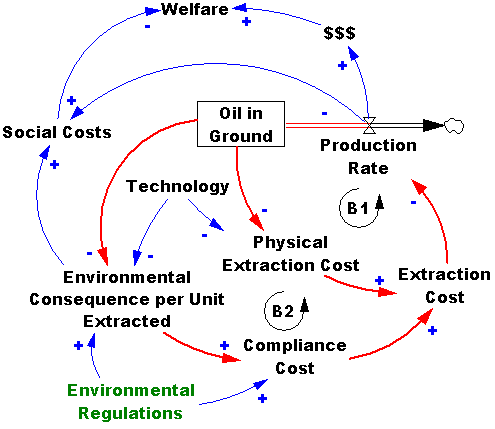

Consider the system:

The underlying mental model behind calls for deregulation sounds like the following: environmental regulations create compliance costs that drive up the total cost of resource extraction, depressing the production rate and depriving the people of needed $$$ and happiness. Certainly that causal path exists. But it’s not the only thing going on.

Those regulations were created for a reason. They reduce environmental impacts, and therefore reduce the unpaid social costs that occur as side effects of oil production and consumption, and therefore improve welfare. These effects are nontrivial, unless you’re a GOP presidential candidate. One could wish for more efficient regulations, but absent that, wishing for less regulation is tantamount to wishing for more environmental consequences and social costs, and hoping that more $$$ will offset that.

Even the basic open-loop rationale for deregulation makes little sense. Resource policy is already loose, so there’s no quantity constraint on production. With the exception of ANWR and some offshore areas, most interesting areas are already leased. Montana certainly doesn’t exercise any foresight in the management of its trust lands. Environmental regulations have hardly become more stringent in the last decade or so. Since oil production in 1999 was higher than it is today, with oil prices well below $20/bbl, so compliance costs must be less than that. So, with oil at $100/bbl, we’d expect an explosion of supply, if regulatory costs were the only constraint. In fact, there’s barely an upward blip, so there must be something else at work…

The real problem is that there’s feedback in the system. For example, there’s balancing loop B1: as you extract more stuff, the remaining resource (oil in the ground) dwindles, and the physical costs of extraction – capital, labor, energy – go up. Technology can stave off that trend for some time, but prices and production trends make it clear that B1 is now dominant. This means that there’s a rather stark better-before-worse tradeoff: if we extract oil more quickly now, to hoist ourselves out of the financial crisis, we’ll have less later. But it seems likely that we’ll be even more desperate later – either to have that oil in an even pricier world market, or to keep it in the ground due to climate concerns. Consider what would have happened if we’d had no environmental constraints on oil production for the last three or four decades. Would the US now have more or less oil to rely on? Would we be happy that we pumped up all that black gold at under $20/bbl? Even the Hotelling rule is telling us that we should leave oil in the ground, as long as prices are rising faster than the interest rate (not hard, at current rates).

Another loop is just gaining traction: B2. As the stock of oil in the ground is depleted, marginal production occurs in increasingly desperate and devastating circumstances. Either you pursue smaller, more remote fields, meaning more drilling and infrastructure disturbance in sensitive areas, or you pursue unconventional resources, like tar sands and shale gas, with resource-intensive methods and unknown hazards. A regulatory rollback would accelerate production via the most destructive extraction methods, right at the time that the physics of extraction is already shifting the balance of private benefits ($$$) and social costs unfavorably. Loop B2 also operates inequitably, much like unemployment. Not everyone is harmed by oil and gas development; the impacts fall disproportionately on the neighbors of projects, who may not even benefit due to severance of surface and mineral rights. This weakens the argument for deregulation even further.

Rather than pretending we can turn the clock back to 1970, we should be thinking carefully about our exit strategy for scarce and climate-constrained resources. There must be lots of things we can do to solve the distributional problems of the current crisis without socializing the costs and privatizing the gains of fossil fuel exploitation more than we already do.