… on another incoherent Breakthrough editorial:

The Creative Destruction of Climate Economics

In the 70 years that have passed since Joseph Schumpeter coined the term “creative destruction,” economists have struggled awkwardly with how to think about growth and innovation. Born of the low-growth agricultural economies of 18th Century Europe, the dismal science to this day remains focused on the question of how to most efficiently distribute scarce resources, not on how to create new ones — this despite two centuries of rapid economic growth driven by disruptive technologies, from the steam engine to electricity to the Internet.

Perhaps the authors should consult the two million references on Google scholar to endogenous growth and endogenous technology, or read some Marx.

There are some important, if qualified, exceptions. Sixty years ago, Nobelist Robert Solow and colleagues calculated that more than 80 percent of long-term growth derives from technological change. But neither Solow nor most other economists offered much explanation beyond that. Technological change was, in the words of one of Solow’s contemporaries, “manna from heaven.”

Climate economics until recently was similarly oriented. Economists mostly treated global warming as a challenge of distributing scarce resources (e.g., the right to pollute), not of creating new ones (e.g., cheap zero carbon energy sources). Climate models treated technological innovation as a given, not as a dependent variable.

Fair enough – I had the same complaint in my dissertation in 1997.

That’s starting to change. Over the last few years, economists have modeled ways to accelerate the innovation of zero carbon power sources. The boldest of these entries to date comes from one of the discipline’s rising stars, MIT’s Daron Acemoglu, along with Philippe Aghion, Leonardo Bursztyn and David Hemous, in a paper published last February in American Economic Review. The paper argues that conventional climate models have overstated the importance of carbon pricing and understated the importance of public investment to encourage technological innovation.

The Economist’s Ryan Avent praised the paper, noting, “economics is clearly moving beyond the carbon-tax-alone position on climate change, which is a good thing.” In fact, Acemoglu and his colleagues went further than Avent suggested. “Optimal policy,” they found, “relies less on a carbon tax, and even more so on a direct encouragement of clean energy technologies.”

While this is a nice paper (related versions here and here), the result is less of a technology blockbuster than Breakthrough would have you believe. It’s highly stylized, particularly with respect to the climate system, so you have to take the quantitative results with a grain of salt. The paper doesn’t consider the class of policies that are thermodynamic losers, like CCS, that will never happen without an emissions price or some other incentive. There are no explicit delays in the innovation process, other than the time step. There’s no explicit supply/demand side separation (green energy vs. efficiency). The range of elasticities of substitution among sources explored is high. There are no problems controlling subsidies to cleantech.

I find the qualitative results very helpful – but the lessons from those don’t match Breakthrough’s typical message:, that R&D in clean energy supply is sufficient to solve the climate problem. In the model, tech-only policy sometimes results in disaster, whereas price-only policy always works, but sometimes at an inefficiently high cost. One situation in which tech-only policy conspicuously fails is a starting point that is close to the brink of environmental catastrophe, in which there isn’t time for tech policy to take hold.

The Acemoglu et al. finding is not that optimal policy implies direct encouragement of cleantech that is somehow “bigger” than a carbon tax. It’s that, given cleantech policy, you can rely less on a carbon tax than you otherwise would, and benefit from a smaller and transient drag on growth. Importantly, they conclude, “(ii) optimal policy involves both ?carbon taxes ?and research subsidies, so that excessive use of carbon taxes can be avoided; (iii) delay in intervention is costly: the sooner and the stronger the policy response, the shorter will the slow growth transition phase be;” In fact, their tables indicate that the benefits of reduced reliance on taxes are much smaller than the costs of delay.

This technological turn within the economics profession comes at a time of three big events in the energy sector.

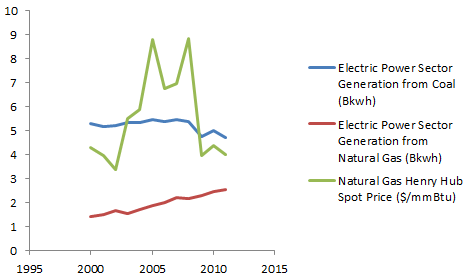

First, more than thirty years of government funding for unconventional gas research, demonstration, and tax credits have contributed to a glut of cheap natural gas, making everything from solar to wind to nuclear uncompetitive, at least in the near-term, while also driving America’s shift from coal to gas.

Second, the tripling of public and private sector investment in clean tech over the last five years has resulted in the price of solar panels declining by 75 percent and wind turbines by 25 percent, after no price declines in the prior five year period.

The causal chain for this would have to be something like clean tech $ triple -> R&D staff hired -> ideas generated -> products implement ideas -> products tested & refined -> factories built -> products sold. It’s totally implausible that all of that happened in five years, unless this is almost exclusively a story about deployment of technologies that were already in the pipeline. In addition, surely “no price declines” had something to do with a booming market, and subsequent price declines are partly an artifact of the subsequent bust, not to mention globalization. Fallacy of the single cause, anyone?

Third, carbon pricing, which many analysts and policy makers believed would be the central mechanism through which nations reduced emissions, has had no measurable impact. If Europe’s Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS) has had any impact on the continent’s emissions, it has been too small to measure with any certainty against falling energy consumption during the recession and large direct subsidies for renewables. Today, the ETS is being used to justify Europe’s reversion to coal.

All of this has sent those who believe carbon pricing should be the highest climate policy priority scrambling. Harvard economist and former Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) Chief Economist Robert Stavins claims that the low carbon prices of the ETS, and its little sister cap and trade system in the US Northeast, known as RGGI, prove not that they’re failing but rather that they are working as planned. The economist Charles Komanoff insists that a carbon tax would not suffer from the same problems as the ETS. And Paul Krugman asserts that a carbon price is still the most important climate policy because… well, because he’s Paul Krugman and he says so.

You can’t prove that pricing isn’t working in the ETS and RGGI, because their prices are roughly zero. Maybe cap & trade isn’t working, but that’s a matter of political emissions allocation, not price-emissions causality. Carbon taxes have been effective in Scandinavia; Krugman and Komanoff might actually know something.

One of the most detailed defenses of a carbon pricing-focused response to climate change comes from the economist Gernot Wagner of EDF, who in a debate with us at Breakthrough Journal credits pricing for the phase-out of leaded gasoline, and for the control of acid rain-causing sulfur dioxide pollution.

But history tells a very different story. In the case of leaded gasoline, eighty percent of the phase-out of leaded gas had already occurred before the establishment of a trading system, due to the ban on the sale of cars that could run on leaded gasoline after 1975, along with local air pollution rules. And the lower-than-expected cost of sulfur dioxide regulation mostly resulted from technological changes that occurred well before the establishment of pollution trading: rail deregulation allowed for the economic shipment of low-sulfur coal, and the development of cheaper scrubbers.

Nevertheless, it remains true that no one would have implemented scrubbers, or shipped coal, without the threat of impending markets or regulation. Fallacy of the single cause, again.

In the end, Wagner implicitly concedes our point, writing, “Yes, acid rain was mostly about deployment–which is/was my point.” In fact, that wasn’t his point. Wagner’s point was that it was the market-based pollution trading mechanism (again: the efficient allocation of a scarce resource) that resulted in the lower costs.

“Similarly,” Wagner writes, “we can achieve US emissions reduction goals for 2020 and possibly even 2030 through deployment of existing technologies.”

But US emissions are today declining not because of cap and trade — it died in the Senate two years ago — but because we are awash in natural gas. And we are awash in gas neither because of caps nor taxes nor regs but because of a government technology push started by Presidents Ford and Carter.

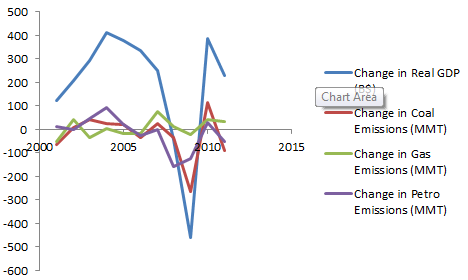

US emissions are declining primarily because we’re awash in unemployment. Substitution of gas for coal in the electric power sector has been an ongoing process, when prices were high as well as low, predating the fracking boom. In other sectors, it’s not clear that gas is substituting for coal (via electricity) – it may be that cheap gas will increase emissions. Since 2005, the biggest decline in emissions has come from petroleum, not coal. That’s primarily transport fuel, where gas is not a ready substitute.

http://www.eia.gov/forecasts/steo/query/

Out of real-world evidence, Wagner falls back on economic theory. “[C]arbon is a pollutant; we need make polluters pay… Price goes up, demand goes down. Economists typically call it the ‘law of demand’–one of the very few laws we’ve got.”

But no exceptions to the law of demand are required to acknowledge that it is the pace and scale of innovation, not the efficient allocation of existing emissions mitigation options, which will most determine the overall cost of mitigating and adapting to climate change.

Is there a law that says the pace and scale of innovation is unresponsive to prices? If not, then might we not consider using prices to create a profit incentive for mitigation innovation? Still more fallacy of the single cause.

In the end, Gernot summed up our disagreement well:

It is, in fact, economics 101 that tells us to cap or tax pollution. It’s economics 102 that teaches us about the process of technical progress, a place where Breakthrough could serve a very useful purpose. Denying economics 101 while trying to make an economics 102 point, though, isn’t the way to go.

Actually, Gernot is exactly right.

But when economics 101 was created in the 18th Century, there were one billion humans on the planet, mostly living on farms, using animals, wood, and dung for energy — about 20 exajoules of it a year. Today, there are seven billion humans, mostly living in cities using electricity and liquid fuels, consuming 430 exajoules of energy annually.

This has nothing to do with Gernot’s point. Markets clear whether you’re talking about dung or thorium. Technical change is a complement to supply and demand, not an alternative.

Over the next century, global energy demand will double, and perhaps triple. But even were energy consumption to stay flat, significantly reducing emissions from today’s levels will require the creation of disruptive new technologies. It’s a task for which a doctrine focused on the efficient allocation of scarce resources could hardly be more ill-suited.

If efficiency doesn’t matter, how exactly do Nordhaus and Shellenberger propose to allocate R&D funding?

— Ted Nordhaus and Michael Shellenberger

The strange thing here is that this is a strawdog controversy. I don’t recall hearing any economists argue that prices are the exclusive climate remedy, and there’s an extensive literature exploring subsidies and other corrections for R&D market failures. Acemoglu et al. say as much:

That we need both a carbon tax and a subsidy to clean research to implement the social optimum (in addition to the subsidy to remove the monopoly distortions) is intuitive: the subsidy deals with future environmental externalities by directing innovation towards the clean sector, whereas the carbon tax deals more directly with the current environmental externality by reducing production of the dirty input. By reducing production in the dirty sector, the carbon tax also discourages innovation in that sector. However, using only the carbon tax to deal with both current environmental externalities and future (knowledge-based) externalities will typically necessitate a higher carbon tax, distorting current production and reducing current consumption excessively.

Frank Ackerman has a second opinion.

I think “reading between the lines” is right because I still have a hard time figuring out what Nordhaus and Co. are really after. Perhaps I just haven’t read enough of their work, but I still don’t see them as flatly against carbon pricing, but rather arguing that our expectations of policy changes as a result of carbon pricing alone are unrealistic. As you so clearly note “the fallacy of the single cause” is a problem for both sides of the issue.

Carbon pricing has gotten the lions share of the attention (at least by the media) while efforts to spurn innovation mainly get attention as political fodder (e.g. Solyndra and Fisker Automotive). Moreover, pricing by itself is a tough sell, while innovation can easily be associated with nationalistic pride.

Ackerman makes the case that really should be the center and that is for both carbon pricing and innovation to be used in tandem. It’s unfortunate that Breakthrough isn’t going after this more directly, but I still think they are mostly trying to bring more attention to the imbalance in both policy and public perception.

It’s fallacy to think that carbon pricing will automagically create the necessary market dynamics to bring CO2 under control, just as it is to think that technology will come as “manna from heaven.” We need to be making deliberate investment choices to create the technology absolutely necessary to make this transition happen and what better way to fund that then a carbon pricing system that helps equalize the true costs of energy in in the market?

It’s the one issue I continue to raise with C-ROADS; the yes I get it, but now what do we actually do about it question. Even if we can get countries to agree on reductions it’s only a criterion for the solution and not the solution itself. Perhaps it comes back to the difference in mindset between scientists and engineers. In the crudest sense scientists understand problems, engineers solve them. The two are not mutually exclusive of course, which is all the more reason to work closely together.

Apparently that isn’t as easy as playing well with others in kindergarten.

One other point about R&D:

The market failure in R&D, due to inability of private parties to fully appropriate the outcome of their work and to capitalize big risks over long horizons is not limited to green energy supply. It also applies to efficiency, health care, business models, etc. Additionally, it’s not really practical to target basic research – materials science is as likely to give you new violin strings as wind turbine blades. That’s why it’s basic.

Therefore it doesn’t really make sense to have a climate-specific R&D policy. We should get our signals (prices, rules) aligned with our goals (stable climate), and then have an R&D policy that helps innovation to serve those goals more efficiently. The result would still be a lot of innovative effort directed to climate-related problems, but in a more natural, bottom-up way.

“We should get our signals (prices, rules) aligned with our goals (stable climate), and then have an R&D policy that helps innovation to serve those goals more efficiently.”

Exactly. This is the point Breakthrough should be making and at the heart of it, I think they believe in. That they have chosen emphasize tech and pooh-pooh the economic perspective is myopic for sure, but I still think they should be seen as allies and not adversaries.

I think with the right model and narrative they could be easily converted to supporting a comprehensive solution that helps to balance the economics, investments, and goals. Projects like Berkeley FIRST and 1BOG have helped make one part of the case while SRECs address another, and new tech like cheaper solar and smart meters and grids fill the other.

Yet it’s not one story. It’s three and it isn’t clear what the scope and scale needed for any of them is. How many coal plants do we need to take offline in the next X years? What percent of homes and the grid converted in the same span? How to distribute the financing? What level of pricing to represent true costs?

The first group with that narrative will be the one to restore sanity across all the groups that are in violent agreement with one another, but just coming from different angles.

I’m not convinced that, in their hearts, they believe in a mixed strategy. Consider this post, for example:

http://thebreakthrough.org/blog/2011/09/the_carbon_tax_then_and_no.shtml

They list 10 reasons why a carbon tax won’t work, then promote a tech-only agenda (AEIC).

They don’t just downplay emissions pricing, or even suggest that it should follow innovation policy. They repeatedly bash it, and brand it and its proponents with pejorative terms like “fetishism”.

I do get some of the points of their 10 reasons. It led me to their original policy piece:

http://thebreakthrough.org/blog/2010/10/postpartisan_summary.shtml

Way down at the bottom in the last item: “4) Internalize the Cost of Energy Modernization” they do finally concede some taxes and fees. Eliminating subsidies would also free up a lot of money to fund some pretty significant ideas. It really does seem like an afterthought though and is more about offsetting costs as opposed to influencing market dynamics.

Pretty single cause thinking.

It’s a crack in the door though and I still think we should wedge it open instead of slamming it shut.

Regarding your point about C-ROADS and the need to bring projections down to the ground (how many coal plants have to go?), I agree. Climate Interactive has a complementary model underway, En-ROADS, that helps with that. It’s tough going, because the system is very complex, and getting at the granular insights (how many turbines, or is gas a bridge to renewables or nowhere) gets in the way of the big picture (long capital lifetimes delay response).

I think the appropriate response is partly, who cares? Figuring out how many wind turbines are needed is a useful reality check (can we source enough steel for the towers quickly?), but really the appropriate response is adaptive – create tech and the incentive to use it, and let the market do its thing, no central planning of coal plants needed.

I didn’t really mean to get granular with “how many coal plants do we shut down,” but rather to estimate the scale of changes that need to happen. My guess is pretty drastic, but I honestly don’t have any data, and that seems like a problem.

How can we know if a shift is even possible, economically? If it isn’t, then what do we need the technology to do (i.e. percent increase in output and/or reduction in cost)? Even for an adaptive response, there will need to be milestones that are aligned with the desired outcome.

If we had done this kind modeling/thinking with ethanol, we probably wouldn’t have wasted our time and resources. It’s not about central planning, it’s about calibrating our actions. Otherwise we end up with marginal solutions (like curbside recycling).

Makes sense.

Out in the market for models, there does seem to be a huge appetite for counting coal plants and wind turbines though. I understand the motivation – foundations want to create detailed scenarios and action plans that they can share. But I think the emphasis is misplaced. Their detailed plans don’t amount to much, because there’s no popular support for implementing them. The REAL need is to build that support, which means teaching people about the very basic elements of the problem – climate bathtubs, delays in action, implications of uncertainty, etc. I wish there was more demand for that.

I too am puzzled by what N&Co seem to be driving at. I don’t think it’s nefarious, though their policy prescriptions are clearly attractive to people who don’t want to do anything soon about climate.

I think the case for guiding R&D with emissions prices is very strong. If you don’t, you’re essentially trying to allocate R&D $ top down, based on a wild guess about what will actually work. For energy supply tech, you might have some success with that, and indeed we already plow quite a bit of money in through DOE programs.

But supply is only a small part of the system of possible tradeoffs in the chain from emissions to welfare. There’s also efficiency (which N&Co pooh-pooh, and derives from a zillion end-uses), there’s sector mix in the economy, and there’s preferences.

Just try to imagine Republicans getting behind DOE doing research on green lifestyles. Yet if you leave out all of this highly decentralized, soft stuff, you probably leave out 2/3 of the solution. The success of a lot of supply and carrier technologies in the marketplace is partly contingent on coordination with efficient end use.

So, a tech-only approach essentially requires you to design a system that evolved (ask the FAA how that worked out for airspace upgrades). Meanwhile, the signals are mixed up, because price continues to guide all decisions in the system, except centralized R&D allocation, toward “emissions don’t matter.”

The likely outcome is that people continue to emit a lot for a long time, and use emerging cleantech to augment their energy use, rather than to reduce emissions.

The Breakthrough counterargument seems to be that the stone age didn’t end because we ran out of rocks, and that people simply aren’t willing to talk about a tax. This is neatly self-fulfilling, if one then dumps on taxes and promotes a tech alternative. But if people are unwilling to make any present sacrifice to avoid future climate consequences through emissions pricing, why should they be willing to do so through R&D subsidies?

For this to work, you have to think that the R&D payoff is so high, the delays so short, and the market share cross-elasticity so high that people won’t notice the spending, and things will take off naturally. But N&Co haven’t made a compelling argument for any of these things. If they could come up with an internally consistent story, embodied in a model, at least there would be some way to have a productive discussion about their proposals.