The principal benefit cited for cap & trade is “environmental certainty,” meaning that “a cap-and-trade system, coupled with adequate enforcement, assures that environmental goals actually would be achieved by a certain date.” Environmental certainty is a bit of a misnomer. I think of environmental certainty as ensuring a reasonable chance of avoiding serious climate impacts. What people mean when they’re talking about cap & trade is really “emissions certainty.” Unfortunately, emissions certainty doesn’t provide climate certainty:

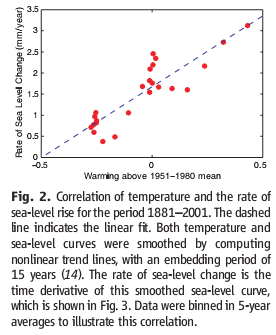

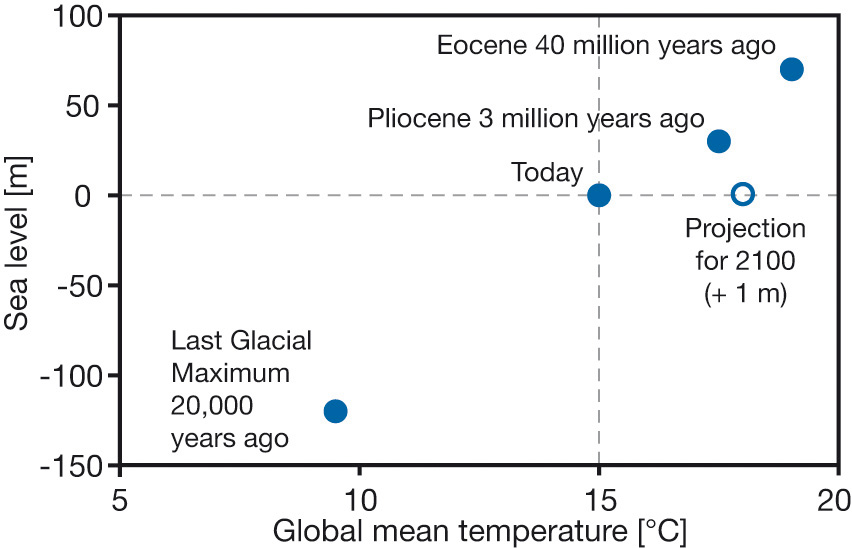

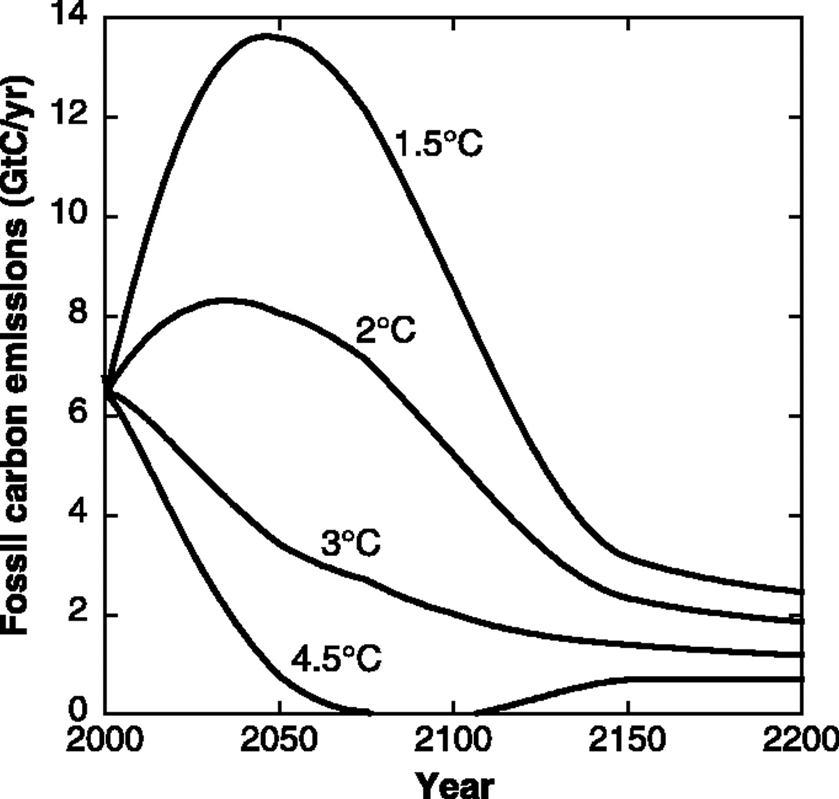

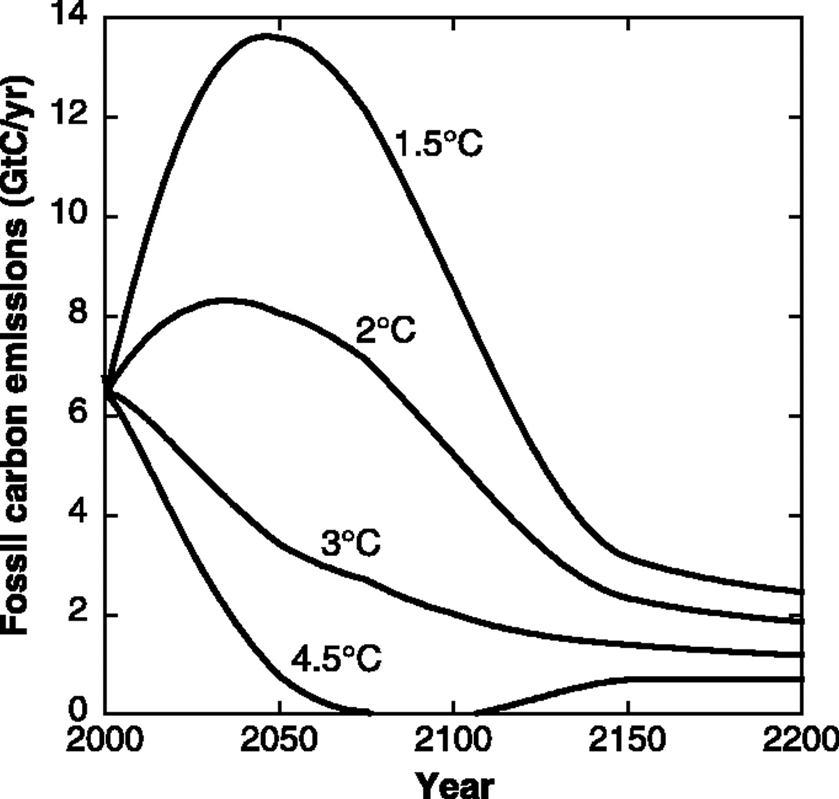

Even if we could determine a “safe” level of interference in the climate system, the sensitivity of global mean temperature to increasing atmospheric CO2 is known perhaps only to a factor of three or less. Here we show how a factor of three uncertainty in climate sensitivity introduces even greater uncertainty in allowable increases in atmospheric CO2 CO2 emissions. (Caldeira, Jain & Hoffert, Science)

The uncertainty about climate sensitivity (not to mention carbon cycle feedbacks and other tipping point phenomena) makes the emissions trajectory we need highly uncertain. That trajectory is also subject to other big uncertainties – technology, growth convergence, peak oil, etc. Together, those features make it silly to expend a lot of effort on detailed plans for 2050. We don’t need a ballistic trajectory; we need a guidance system. I’d like to see us agree to a price on GHGs everywhere now, along with a decision rule for adapting that price over time until we’re on a downward emissions trajectory. Then move on to the other legs of the stool: ensuring equitable opportunities for development, changing lifestyle, tackling institutional barriers to change, and investing in technology.

Unfortunately, cap & trade seems ill-suited to adaptive control. Emissions commitments and allowance allocations are set in multi-year intervals, announced in advance, with long lead times for design. Financial markets and industry players want that certainty, but the delay limits responsiveness. Decision makers don’t set the commitment by strictly environmental standards; they also ask themselves what allocation will result in an “acceptable” price. They’re risk averse, so they choose an allocation that’s very likely to lead to an acceptable price. That means that, more often than not, the system will be overallocated. On balance, their conservatism is probably a good thing; otherwise the whole system could unravel from a negative public reaction to volatile prices. Ironically, safety valves – one policy that could make cap & trade more robust, and thus enable better mean performance – are often opposed because they reduce emissions certainty.