Following its misguided attack on complex CLDs, a few of us wrote a letter to the NYTimes. Since they didn’t publish, here it is:

Dear Editors, Systemic Spaghetti Slide Snookers Scribe. Powerpoint Pleases Policy Players

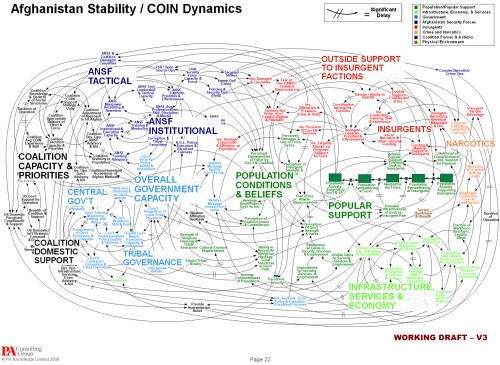

“We Have Met the Enemy and He Is PowerPoint” clearly struck a deep vein of resentment against mindless presentations. However, the lead “spaghetti” image, while undoubtedly too much to absorb quickly, is in fact packed with meaning for those who understand its visual lingo. If we can’t digest a mere slide depicting complexity, how can we successfully confront the underlying problem?

The diagram was not created in Powerpoint. It is a “causal loop diagram,” one of a several ways to describe relationships that influence the evolution of messy problems like the war in the Middle East. It’s a perfect illustration of General McMaster’s observation that, “Some problems in the world are not bullet-izable.” Diagrams like this may not be intended for public consumption; instead they serve as a map that facilitates communication within a group. Creating such diagrams allows groups to capture and improve their understanding of very complex systems by sharing their mental models and making them open to challenge and modification. Such diagrams, and the formal computer models that often support them, help groups to develop a more robust understanding of the dynamics of a problem and to develop effective and elegant solutions to vexing challenges.

It’s ironic that so many call for a return to pure verbal communication as an antidote for Powerpoint. We might get a few great speeches from that approach, but words are ill-suited to describe some data and systems. More likely, a return to unaided words would bring us a forgettable barrage of five-pagers filled with laundry-list thinking and unidirectional causality.

The excess supply of bad presentations does not exist in a vacuum. If we want better presentations, then we should determine why organizational pressures demand meaningless propaganda, rather than blaming our tools.

Tom Fiddaman of Ventana Systems, Inc. & Dave Packer, Kristina Wile, and Rebecca Niles Peretz of The Systems Thinking Collaborative

Other responses of note:

We have met an ally and he is Storytelling (Chris Soderquist)

Why We Should be Suspect of Bullet Points and Laundry Lists (Linda Booth Sweeney)