SDM has a new post about failure modes in DoD procurement. One of the key dynamics is firefighting:

For example, McNew was working on a radar system attached to the belly of airplanes so they could track enemy ground movements for targeting by both ground and air fighters. “The contractor took used 707s,” McNew explains, “tore them down to the skin and stringers, determined their structural soundness, fixed what needed fixing, and then replaced the old systems and attached the new radar system.” But when the plane got to the last test station, some structural problems still had not been fixed, meaning the systems that had been installed had to be ripped out to fix the problems, and then the systems had to be reinstalled. In order to get that last airplane out the door on time, firefighting became the order of the day. “We had most of the people in the plant working on that one plane while other planes up the line were falling farther and farther behind schedule.”

Says McNew, putting on his systems thinking hat, “You think you’re going to get a one-to-one ratio of effort-to-result but you don’t. There’s no linear correlation. The project you’re firefighting isn’t helped as much as you think it will be, and the other project falls farther behind as it’s operating with fewer resources. In other words, you’ve doubled the dysfunction.

This has been well-characterized by a bunch of modeling work at MIT’s SD group. It’s hard to find at the moment, because Sloan seems to have vandalized its own web site. Here’s a sampling of what I could lay my hands on:

From Laura Black & Nelson Repenning in the SDR, Why Firefighting Is Never Enough: Preserving High-Quality Product Development:

… we add to insights already developed in single-project models about insufficient resource allocation and the “firefighting” and last-minute rework that often result by asking why dysfunctional resource allocation persists from project to project. …. The main insight of the analysis is that under-allocating resources to the early phases of a given project in a multi-project environment can create a vicious cycle of increasing error rates, overworked engineers, and declining performance in all future projects. Policy analysis begins with those that were under consideration by the organization described in our data set. Those policies turn out to offer relatively low leverage in offsetting the problem. We then test a sequence of new policies, each designed to reveal a different feature of the system’s structure and conclude with a strategy that we believe can significantly offset the dysfunctional dynamics we discuss. ….

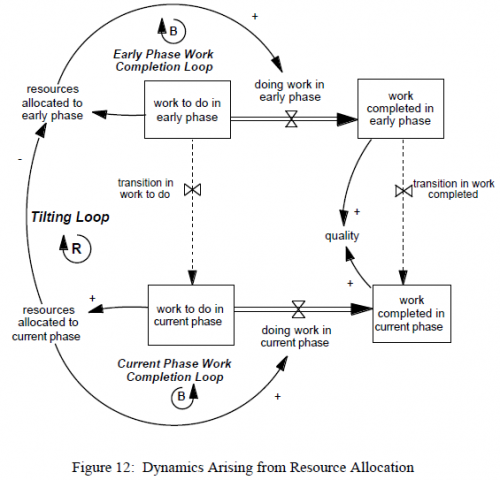

The key dynamic is what they term tilting – a positive feedback that arises from the interactions among early and late phase projects. When a late phase project is in trouble, allocating more resources to it is the natural response (put out the fire; part of the balancing late phase work completion loop). The perverse side effect is that, with finite resources, firefighting steals from early phase projects that are tomorrow’s late phase projects. That means that, down the road, those projects – starved for resources earlier in their life – will be in even more trouble, and steal more resources from the next generation of early phase projects. Thus the descent into permanent firefighting begins …

The positive feedback of tilting creates a trap that can snare incautious organizations. In the presence of such traps, well-intentioned policies can turn vicious.

… testing plays a paradoxical role in multi-project development environments. On the one hand, it is absolutely necessary to preserve the integrity of the final product. On the other hand, in an environment where resources are scarce, allocating additional resources to testing or to addressing the problems that testing identifies leaves fewer resources available to do the up-front work that prevents problems in the first place in subsequent projects. Thus, while a decision to increase the amount of testing can yield higher quality in the short run, it can also ignite a cycle of greater-than-expected resource requirements for projects in downstream phases, fewer resources allocated to early upstream phases, and increasingly delayed discovery of major problems.

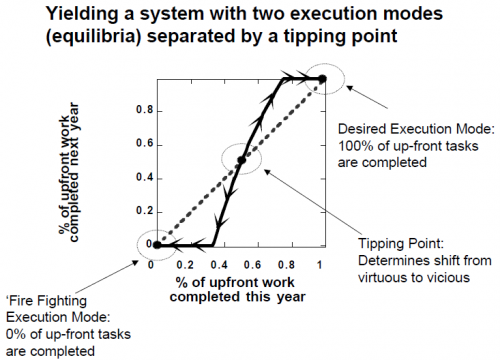

In related work with a similar model, Repenning characterizes the tilting dynamic with a phase plot that nicely illustrates the point:

To read the phase plot, start at any point on the horizontal axis, read up to the solid black line and then over to the vertical axis. So, for example, suppose that, in a given model year, the organization manages to accomplish about 60 percent of its planned concept development work, what happens next year? Reading up and over suggests that, if it accomplishes 60 percent of the up-front work this year, the dynamics of the system are such that about 70 percent of the up-front work will get done next year. Determining what happens in a subsequent model year requires simply returning to the horizontal axis and repeating; accomplishing 70 percent this year leads to almost 95 percent being accomplished in the year that follows. Continuing this mode of analysis shows that, if the system starts at any point to the right of the solid black circle in the center of the diagram, over time the concept development completion fraction will continue to increase until it reaches 100%. Here, the positive loop works as a virtuous cycle: Each year a little more up front work is done, decreasing errors and, thereby, reducing the need for resources in the downstream phase. …

In contrast, however, consider another example. Imagine this time that the organization starts to the left of the solid black dot and accomplishes only 40 percent of its planned concept development activities. Now, reading up and over, shows that instead of completing more early phase work in the next year, the organization completes less—in this case only about 25 percent. In subsequent years, the completion fraction declines further, creating a vicious cycle of declining attention to upfront activities and increasing error rates in design work. In this case, the system converges to a mode in which concept development work is ignored in favor of fixing problems in the downstream project.

The phase plot thus reveals two important features of the system. First, note from the discussion above that anytime the plot crosses the forty-five degree line … the execution mode in question will repeat itself. Formally, at these points the system is said to be in equilibrium. Practically, equilibria represent the possible “steady states” in the system, the execution modes that, once reached, are self-sustaining. As the plot highlights, this system has three equilibria (highlighted by the solid black circles), two at the corners and one in the center of the diagram.

Second, also note that the equilibria do not have identical characteristics. The equilibria at the two corners are stable, meaning that small excursions will be counteracted. If, for example, the system starts in the desired execution mode … and is slightly perturbed, perhaps pushing the completion fraction down to 60%, then, as the example above highlights, over time the system will return to the point from which it started …. Similarly, if the system starts at f(s)=0 and receives an external shock, perhaps moving it to a completion fraction of 40%, then it will also eventually return to its starting point. The arrows on the plot line highlight the “direction” or trajectory of the system in disequilibrium situations. In contrast to those at the corners, the equilibrium at the center of the diagram is unstable (the arrows head “away” from it), meaning small excursions are not counteracted. Instead, once the system leaves this equilibrium, it does not return and instead heads toward one of the two corners. …

Formally, the unstable equilibrium represents the boundary between two basins of attraction. …. This boundary, or tipping point, plays a critical role in determining the system’s behavior because it is the point at which the positive loop changes direction. If the system starts in the desirable execution mode and then is perturbed, if the shock is large enough to push the system over the tipping point, it does not return to its initial equilibrium and desired execution mode. Instead, the system follows a new downward trajectory and eventually becomes trapped in the fire fighting equilibrium.

You’ll have to read the papers to get the interesting prescriptions for improvement, plus some additional dynamics of manager perceptions that accentuate the trap.

Stay tuned for a part II on this topic.