That’s the title of a cool article at Plus. Click the image to check it out:

Writing an SD Conference Paper

It’s review time for SD conference papers again. As usual, there’s a lot of variance in quality: really good stuff, stuff that isn’t SD, and good ideas imprisoned in a bad presentation. A few thoughts on how to write a good conference paper, in no particular order:

- Read a bunch of good SD papers, by browsing the SD Review, Dynamica, Desert Island Dynamics, or past conference plenary papers. You could do a lot worse than picking one as a model for your paper.

- Start with: What’s the question? Why do we care? Who’s the audience? How will they be influenced? What is their prevailing mental model, and how must it change for things to improve? (If your paper is a methods paper, not a model paper, perhaps the relevant questions are different, but it’s still nice to know why I’m reading something up front.)

- If you have a model,

- Make sure units balance, stocks and flows are conserved, structure is robust in extreme conditions, and other good practices are followed. When in doubt, refer to Industrial Dynamics or Business Dynamics.

- Provide a high-level diagram.

- Describe what’s endogenous, what’s exogenous, and what’s excluded.

- Provide some basic stats – What’s the time horizon? How many state variables are there?

- Provide some data on the phenomena in question, or at least reference modes and a dynamic hypothesis.

- Discuss validation – how do we know your model is any good?

- Discuss “Which Policy Run is Best, and Who Says So?” (See DID for the reference).

- Provide the model in supplementary material, if at all possible.

- Use intelligible and directional variable names.

- Clearly identify the parameter changes used to generate each run.

- Change only one thing at a time in your simulation experiments (or more generally, use scientific method).

- Explore uncertainty.

- If your output shows interesting dynamics (or weird discontinuities and other artifacts), please explain.

- Most importantly, clearly explain why things are happening by relating behavior to structure. Black-box output is boring. Causal loop diagrams or simplified stock-flow schematics may be helpful for explaining the structure of interest.

- If you use CLDs, Read Problems with Causal Loop Diagrams and Guidelines for Drawing Causal Loop Diagrams and Chapter 5 of Business Dynamics.

- Archetypes are a compact way to communicate a story, but don’t assume that everyone knows them all. Don’t shoehorn your problem into an archetype; if it doesn’t fit, describe the structure/behavior in its own right.

- If you present graphs, label axes with units, clearly identify each series, etc. Follow general good practice for statistical graphics. I like lots of graphs because they’re information-rich, but each one should have a clear purpose and association with the text. Screenshots straight out of some modeling packages are not presentation-quality in my opinion.

- I don’t think it’s always necessary to follow the standard scientific journal article format, it could even be boring, but when in doubt it’s not a bad start.

- If your English is not the best (perhaps even if it is), at least seek help editing your abstract, so that it’s clear and succinct.

- Ask yourself whether your paper is really about system dynamics. If you have a model, is it dynamic? Is it behavioral? Does it employ an operational description of the system under consideration? If you’re describing a method, is it applicable to (possibly nonlinear) dynamic systems? If you’re describing a process (group modeling, for example), does it involve decision making or inquiry into a dynamic system? I welcome cross-disciplinary papers, but I think pure OR papers (say, optimizing a shop-floor layout) belong at OR conferences.

- Do a literature search, especially of the SD Review and SD bibliography, but also of literature outside the field, so that you can explain how the model/method relates to past work in SD and to different perspectives elsewhere. Usually it’s not necessary to report all the gory details of other papers though.

- Can’t think of a topic? Replicate a classic SD model or a model from another field and critique it. See Christian Erik Kampmann, “Replication and revision of a classic system dynamics model: Critique of ‘Population Control Mechanisms’ System Dynamics Review 7(2), 1991. Or try this.

- Rejected anyway? Don’t feel bad. Try again next year!

Battle of the Bulb

The NYT covers the resistance movement against incandescent light bulb bans. I think most of the resistance’s arguments are flimsy. Good-quality CFLs have better color reproduction and much longer lifetimes than incandescents. Start up times are now pretty fast, flicker is not a problem, and cold weather operation is fine outdoors, even here in Montana. Bad-quality bulbs are more problematic, but you get what you pay for; if you pay for quality, you still come out ahead with CFLs.

Still, I sympathize with the resistance, because an outright ban makes little sense. CFLs don’t work in some applications, and don’t even save energy or money when used in locations that are infrequently on. They also make lousy chicken incubators. Instead, we should ban inefficient lighting economically, by pricing GHGs, local air quality, light pollution, energy security, and whatever else motivates us to seek efficient lighting in the first place. Then incandescents can stick around for things that make sense, and disappear for things that don’t. The resistance won’t have to hoard bulbs, because they can run their little tungsten filaments as long as they feel like paying for the privelege. While we’re at it, we should price mercury, so the indoor and outdoor pollution effects of CFL disposal and coal combustion are properly traded off.

Command and control is so 20th century.

Aerosols and the Climate Bathtub

From RealClimate:

Over the mid-20th century, sulfate precursor emissions appear to have been so large that they more then compensated for greenhouse gases, leading to a slight cooling in the Northern Hemisphere. During the last 3 decades, the reduction in sulfate has reversed that cooling, and allowed the effects of greenhouse gases to clearly show. In addition, black carbon aerosols lead to warming, and these have increased during the last 3 decades.

For an analogy, picture a reservoir. Say that around the 1930s, rainfall into the watershed supplying the reservoir began to increase. However, around the same time, a leak developed in the dam. The lake level stayed fairly constant as the rainfall increased at about the same rate the leak grew over the next few decades. Finally, the leak was patched (in the early 70s). Over the next few decades, the lake level increased rapidly. Now, what’s the cause of that increase? Is it fair to say that lake level went up because the leak was fixed? Remember that if the rainfall hadn’t been steadily increasing, then the leak would have led to a drop in lake levels whereas fixing it would have brought the levels back to normal. However, it’s also incomplete to ignore the leak, because then it seems puzzling that the lake levels were flat despite the increased rain during the first few decades and that, were you to compare the increased rain with the lake level rise, you’d find the rise was more rapid during the past three decades than you could explain by the rain changes during that period. You need both factors to understand what happened, as you need both greenhouse gases and aerosols to explain the surface temperature observations (and the situation is more complex than this simple analogy due to the presence of both cooling and warming types of aerosols).

Read the rest: Yet More Aerosols

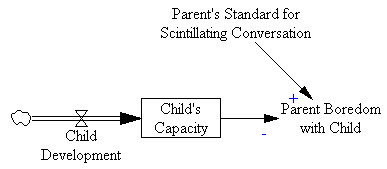

If your kids are boring, you're doing it wrong

The other day I ran across a blog post (undeserving of a link, though there is a certain voyeuristic fascination to be had in reading it) that described children as boring little wretches, unsuited to inhabit the cerebral stratosphere of their elders. The mental model seemed to be something like the following:

The policy response to the misfortune of having children implied by the above is to foist them off on TV and day care until they grow up enough that you can tolerate their presence. That leaves you plenty of time for more intellectual pursuits, like tweeting, or speculating about the romance of the person in the next cubicle.

This reminded me of an earlier perspective on children, now thankfully less prevalent:

Their Hearts naturally, are a meer nest, root, fountain of Sin, and wickedness; an evil Treasure from whence proceed evil things viz. Evil Thoughts. Murders, Adulteries &c. Indeed, as sharers in the guilt of Adam’s first Sin, they’re Children of Wrath by Nature, liable to Eternal Vengeance, the Unquencheable Flames of Hell. – Benjamin Wadsworth

Continue reading “If your kids are boring, you're doing it wrong”

Coyote

Bonn – Are Developing Countries Asking For the Wrong Thing?

Yesterday’s news:

BONN, Germany (Reuters) – China, India and other developing nations joined forces on Wednesday to urge rich countries to make far deeper cuts in greenhouse gas emissions than planned by 2020 to slow global warming.

I’m sure that the mental model behind this runs something like, “the developed world created most of the problem up to this point, and they’re rich, so they should get busy making deep cuts, while we grow a little more to catch up.” Regardless of fairness considerations, that approach ignores the physics of the situation. If developing countries continue to increase emissions, it hardly matters how deep cuts are in the rich world. Either everyone plays along, or mitigation doesn’t work.

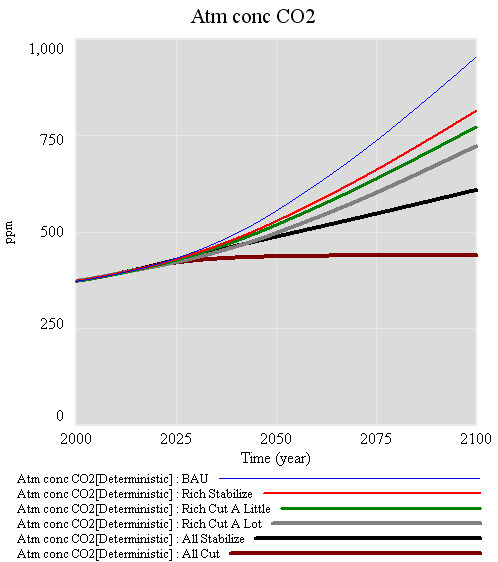

I fired up C-ROADS and ran a few scenarios to illustrate:

The top blue line is the AIFI business-as-usual, with rapid emissions growth. If rich nations stabilize emissions as of today, you get the red line – still much more than 2x CO2 at the end of the century. Whether the rich start cutting emissions a little (1%/yr, green) or a lot (5%/yr, green) after that makes relatively little difference, because emissions from the rich world quickly become a small share of the total. Getting everyone to merely stabilize emissions (at 2009 levels for the rich, 2020 for developing countries, black) makes a substantially bigger difference than deep cuts by the rich alone. Stabilizing CO2 in the atmosphere at a low level requires deep cuts by everyone (here 4%/year, brown).

If we’re serious about stabilization, it doesn’t make sense for the rich to decarbonize faster, so that the developing world can construct more carbon-dependent capital that will ultimately have to be deconstructed. It may sound “fair” in carbon-per-capita terms, but I don’t think that’s a very good measure of human welfare, and it’s unlikely to end up with a fair distribution of damages.

If the developing countries are really concerned about climate impacts (as they should be), they should be looking to the rich world for help getting onto a low-carbon path today, not in 20 years. They should also be willing to impose a carbon price on themselves. It won’t collapse their economies any more than it will ours. Without a price on carbon, rebound effects and leakage will eat up most gains, as the private sector responds to the real signal: “go green (but the price of carbon is zero, wink wink nudge nudge).” Their request to the rich should be about the transfers, property rights, and other changes it takes to get the job done with some measure of distributional fairness (a topic that won’t be popular in some circles).

RealClimate Admits Error, Shutters Site

Reactions to Waxman Markey

My take: It’s a noble effort, but flawed. The best thing about it is the broad, upstream coverage of >85% of emissions. However, there are too many extraneous pieces operating alongside the cap. Those create possible inefficiencies, where the price of carbon is nonuniform across the economy, and create a huge design task and administrative burden for EPA. It would be better to get a carbon price in place, then fiddle with RPS, LCFS, and other standards and programs as needed later. The deep cuts in emissions reflect what it takes to change the climate trajectory, but I’m concerned that the trajectory is too rigid to cope with uncertainty, even with the compliance period, banking, borrowing, and strategic reserve provisions. So-called environmental certainty isn’t helpful if it causes price volatility that leads to the undoing of the program. As always, I’d rather see a carbon tax, but I think we could work with this framework if we have to. Allowance allocation is, of course, the big wrestling match to come.

The WSJ has a quick look

Joe Romm gives it a B+

GreenPeace says it’s a good first step

USCAP likes it (they should, a lot of it is their ideas):

USCAP hails the discussion draft released by Chairmen Waxman and Markey as a strong starting point for enacting legislation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The discussion draft provides a solid foundation to create a climate strategy that both protects our economy and achieves the nation’s environmental goals. It recognizes that many of these issues are tightly linked and must be dealt with simultaneously. We appreciate the thoughtful approach reflected in the draft and the priority the Chairmen are placing on this important issue.

The draft addresses most of the core issues identified by USCAP in our Blueprint for Legislative Action and reflects many of our policy recommendations. Any climate program must promote private sector investment in vital low-carbon technologies that will create new jobs and provide a foundation for economic recovery. Legislation must also protect consumers, vulnerable communities and businesses while ensuring economic sustainability and environmental effectiveness.

The API hasn’t reacted, but the IPAA has coverage on its blog

CEI hates it.

Rush Limbaugh says it’ll finish us off,

RUSH: Henry Waxman’s just about finished his global warming energy bill, 648 pages, as the Democrats prepare to finish off what’s left of the United States. Folks, we have got to drive these people out of office. We have to start now. The Republicans in Congress need to start throwing every possible tactic in front of everything the Democrats are trying to do. This is getting absurd. Listen to this. Henry Waxman and Edward Markey are putting the finishing touches on a 648-page global warming and energy bill that will certainly finish this country off. They’re circulating the bill today. The text of the bill ought to be up soon at a website called globalwarming.org. The bill contains everything you’d expect from an Algore wish list. Reading this, I don’t know how this will not raise energy prices to crippling levels and finish off the auto industry as we know it. (More here)

Time points out that the Senate could be a dealbreaker:

The effects of the already-intense lobbying around the issue were being felt across the Capitol, where the Senate the same afternoon passed by an overwhelming margin an amendment resolving that any energy legislation should not increase electricity or gas prices.

That’ll make it tough to get 60 votes.

Draft Climate Bill Out

AP has the story. The House Committee on Energy and Commerce has the draft. From the summary:

The legislation has four titles: (1) a ‘clean energy’ title that promotes renewable sources of energy and carbon capture and sequestration technologies, low-carbon transportation fuels, clean electric vehicles, and the smart grid and electricity transmission; (2) an ‘energy efficiency’ title that increases energy efficiency across all sectors of the economy, including buildings, appliances, transportation, and industry; (3) a ‘global warming’ title that places limits on the emissions of heat-trapping pollutants; and (4) a ‘transitioning’ title that protects U.S. consumers and industry and promotes green jobs during the transition to a clean energy economy.

One key issue that the discussion draft does not address is how to allocate the tradable emission allowances that restrict the amount of global warming pollution emitted by electric utilities, oil companies, and other sources. This issue will be addressed through discussions among Committee members.

A few quick observations, drawing on the committee summary (the full text is 648 pages and I don’t have the appetite): Continue reading “Draft Climate Bill Out”