Areva pursues “defense in depth” for reactor safety:

Areva SA (CEI) Chief Executive Officer Anne Lauvergeon said explosions at a Japanese atomic power site in the wake of an earthquake last week underscore her strategy to offer more complex reactors that promise superior safety.

“Low-cost reactors aren’t the future,” Lauvergeon said on France 2 television station yesterday. “There was a big controversy for one year in France about the fact that our reactors were too safe.”

Lauvergeon has been under pressure to hold onto her job amid delays at a nuclear plant under construction in Finland. The company and French utility Electricite de France SA, both controlled by the state, lost a contract in 2009 worth about $20 billion to build four nuclear stations in the United Arab Emirates, prompting EDF CEO Henri Proglio to publicly question the merits of Areva’s more complex and expensive reactor design.

Areva’s new EPR reactors, being built in France, Finland and China, boasts four independent safety sub-systems that are supposed to reduce core accidents by a factor 10 compared with previous reactors, according to the company.

The design has a double concrete shell to withstand missiles or a commercial plane crash, systems designed to prevent hydrogen accumulation that may cause radioactive release, and a core catcher in the containment building in the case of a meltdown. To withstand severe earthquakes, the entire nuclear island stands on a single six-meter (19.6 feet) thick reinforced concrete base, according to Paris-based Areva.

I don’t doubt that the Areva design is far better than the reactors now in trouble in Japan. But I wonder if this is really the way forward. Big, expensive hardware that uses multiple redundant safety systems to offset the fundamentally marginal stability of the reaction might indeed work safely, but it doesn’t seem very deployable on the kind of scale needed for either GHG emissions mitigation or humanitarian electrification of the developing world. The financing comes in overly large bites, huge piles of concretes increase energy and emission payback periods, and it would take ages to ramp up construction and training enough to make a dent in the global challenge.

I suspect that the future – if there is one – lies with simpler designs that come in smaller portions and trade some performance for inherent stability and antiproliferation features. I can’t say whether their technology can actually deliver on the promises, but at least TerraPower – for example – has the right attitude:

“A cheaper reactor design that can burn waste and doesn’t run into fuel limitations would be a big thing,” Mr. Gates says.

However, even simple/small-is-beautiful may come rather late in the game from a climate standpoint:

While Intellectual Ventures has caught the attention of academics, the commercial industry–hoping to stimulate interest in an energy source that doesn’t contribute to global warming–is focused on selling its first reactors in the U.S. in 30 years. The designs it’s proposing, however, are essentially updates on the models operating today. Intellectual Ventures thinks that the traveling-wave design will have more appeal a bit further down the road, when a nuclear renaissance is fully under way and fuel supplies look tight. – Technology Review

Not surprisingly, the evolution of the TerraPower design relies on models,

Myhrvold: When you put a software guy on an energy project he turns it into a software project. One of the reasons were innovating around nuclear is that we put a huge amount of energy into computer modeling. We do very extensive computer modeling and have better computer modeling of reactor internals than anyone in the world. No one can touch us on software for designing the reactor. Nuclear is really expensive to do experiments on, so when you have good software it’s way more efficient and a shorter design cycle.

Computing is something that is very important for nuclear. The first fast reactors, which TerraPower is, were basically designed in the slide rule era. It was stunning to us that the guys back then did what they did. We have these incredibly accurate simulations of isotopes and these guys were all doing it with slide rules. My cell phone has more computing power than the computers that were used to design the world’s nuclear plants.

It’ll be interesting to see whether current events kindle interest in new designs, or throw the baby out with the bathwater (is it a regular baby, or a baby Godzilla?). From a policy standpoint, the trick is to create a level playing field for competition among nuclear and non-nuclear technologies, where government participation in the fuel cycle has been overwhelming and risks are thoroughly socialized.

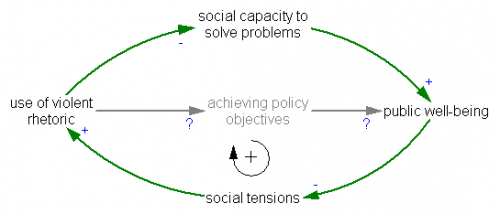

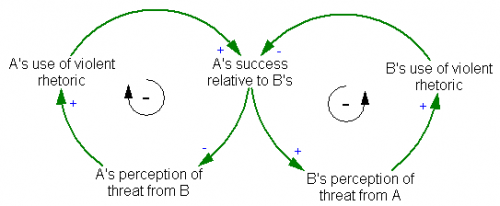

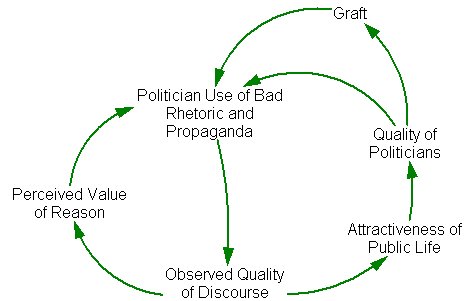

In the escalation archetype, two sides struggle to maintain an advantage over each other. This creates two inner negative feedback loops, which together create a positive feedback loop (a figure-8 around the two negative loops). It’s interesting to note that, so far, the use of violent rhetoric is fairly one-sided – the escalation is happening within the political right (candidates vying for attention?) more than between left and right.

In the escalation archetype, two sides struggle to maintain an advantage over each other. This creates two inner negative feedback loops, which together create a positive feedback loop (a figure-8 around the two negative loops). It’s interesting to note that, so far, the use of violent rhetoric is fairly one-sided – the escalation is happening within the political right (candidates vying for attention?) more than between left and right. The positive feedbacks around violent rhetoric create a societal trap, from which it may be difficult to extricate ourselves. If there’s a general systems insight about vicious cycles, it’s that the best policy is prevention – just don’t start down that road (if you doubt this, play the

The positive feedbacks around violent rhetoric create a societal trap, from which it may be difficult to extricate ourselves. If there’s a general systems insight about vicious cycles, it’s that the best policy is prevention – just don’t start down that road (if you doubt this, play the