The vision of teacher value added modeling (VAM) is a good thing: evaluate teachers based on objective measures of their contribution to student performance. It may be a bit utopian, like the cybernetic factory, but I’m generally all for substitution of reason for baser instincts. But a prerequisite for a good control system is a good model connected to adequate data streams. I think there’s reason to question whether we have these yet for teacher VAM.

The VAM models I’ve seen are all similar. Essentially you do a regression on student performance, with a dummy for the teacher, and as many other explanatory variables as you can think of. Teacher performance is what’s left after you control for demographics and whatever else you can think of. (This RAND monograph has a useful summary.)

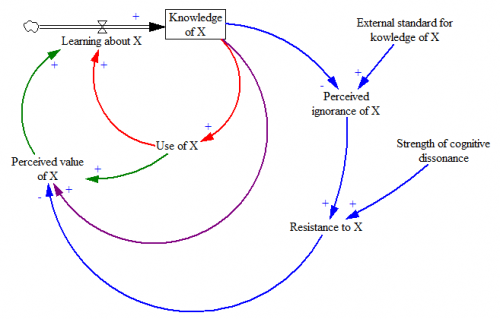

Right away, you can imagine lots of things going wrong. Statistically, the biggies are omitted variable bias and selection bias (because students aren’t randomly assigned to teachers). You might hope that omitted variables come out in the wash for aggregate measurements, but that’s not much consolation to individual teachers who could suffer career-harming noise. Selection bias is especially troubling, because it doesn’t come out in the wash. You can immediately think of positive-feedback mechanisms that would reinforce the performance of teachers who (by mere luck) perform better initially. There might also be nonlinear interaction affects due to classroom populations that don’t show up as the aggregate of individual student metrics.

On top of the narrow technical issues are some bigger philosophical problems with the measurements. First, they’re just what can be gleaned from standardized testing. That’s a useful data point, but I don’t think I need to elaborate on its limitations. Second, the measurement is a one-year snapshot. That means that no one gets any credit for building foundations that enhance learning beyond a single school year. We all know what kind of decisions come out of economic models when you plug in a discount rate of 100%/yr.

The NYC ed department claims that the models are good:

Q: Is the value-added approach reliable?

A: Our model met recognized standards for validity and reliability. Teachers’ value-added scores were positively correlated with school Progress Report scores and principals’ evaluations of teacher effectiveness. A teacher’s value-added score was highly stable from year to year, and the results for teachers in the top 25 percent and bottom 25 percent were particularly stable.

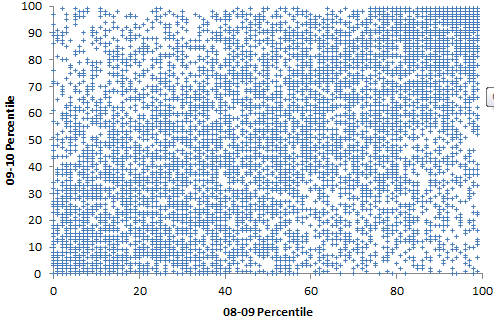

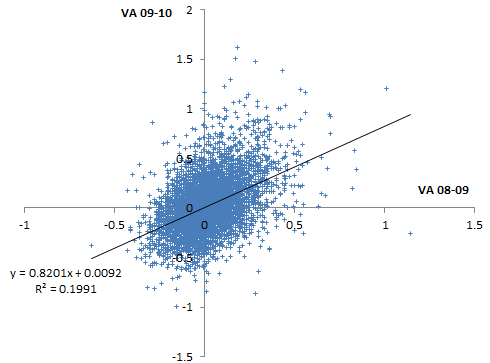

That’s odd, because independent analysis by Gary Rubinstein of FOI released data indicates that scores are highly unstable. I found that hard to square with the district’s claims about the model, above, so I did my own spot check:

Percentiles are actually not the greatest measure here, because they throw away a lot of information about the distribution. Also, the points are integers and therefore overlap. Here are raw z-scores:

Percentiles are actually not the greatest measure here, because they throw away a lot of information about the distribution. Also, the points are integers and therefore overlap. Here are raw z-scores:

Some things to note here:

Some things to note here:

- There is at least some information here.

- The noise level is very high.

- There’s no visual evidence of the greater reliability in the tails cited by the district. (Unless they’re talking about percentiles, in which case higher reliability occurs almost automatically, because high ranks can only go down, and ranking shrinks the tails of the distribution.)

The model methodology is documented in a memo. Unfortunately, it’s a typical opaque communication in Greek letters, from one statistician to another. I can wade through it, but I bet most teachers can’t. Worse, it’s rather sketchy on model validation. This isn’t just research, it’s being used for control. It’s risky to put a model in such a high-stakes, high profile role without some stress testing. The evaluation of stability in particular (pg. 21) is unsatisfactory because the authors appear to have reported it at the performance category level rather than the teacher level, when the latter is the actual metric of interest, upon which tenure decisions will be made. Even at the category level, cross-year score correlations are very low (~.2-.3) in English and low (~.4-.6) in math (my spot check results are even lower).

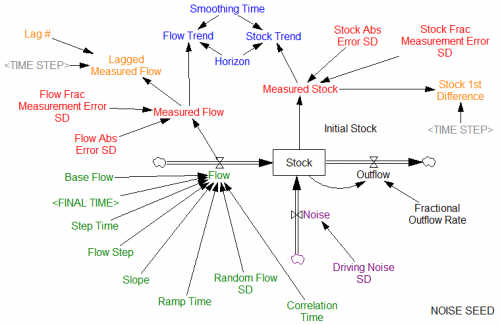

What’s really needed here is a full end-to-end model of the system, starting with a synthetic data generator, replicating the measurement system (the 3-tier regression), and ending with a population model of teachers. That’s almost the only way to know whether VAM as a control strategy is really working for this system, rather than merely exercising noise and bias or triggering perverse side effects. The alternative (which appears to be underway) is the vastly more expensive option of experimenting with real $ and real people, and I bet there isn’t adequate evaluation to assess the outcome properly.

Because it does appear that there’s some information here, and the principle of objective measurement is attractive, VAM is an experiment that should continue. But given the uncertainties and spectacular noise level in the measurements, it should be rolled out much more gradually. It’s bonkers for states to hang 50% of a teacher’s evaluation on this method. It’s quite ironic that states are willing to make pointed personnel decisions on the basis of such sketchy information, when they can’t be moved by more robust climate science.

Really, the thrust here ought to have two prongs. Teacher tenure and weeding out the duds ought to be the smaller of the two. The big one should be to use this information to figure out what makes better teachers and classrooms, and make them.

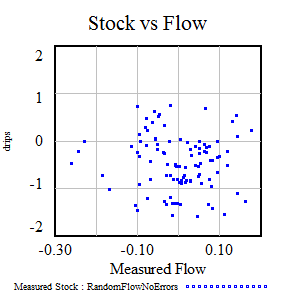

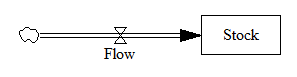

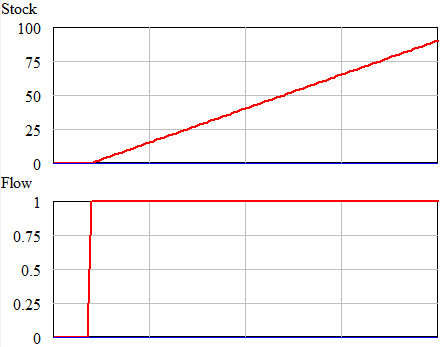

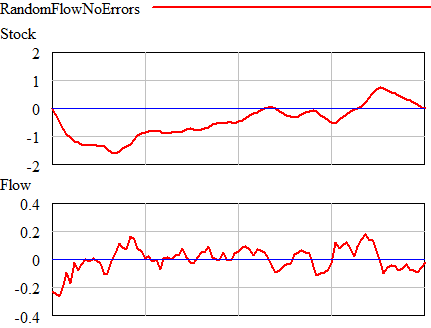

Once could actually draw some superstitious conclusions about the stock and flow time series above by breaking them into apparent episodes, but that’s quite likely to mislead unless you’re thinking explicitly about the bathtub. Looking at a stock-flow scatter plot, it appears that there is no relationship:

Once could actually draw some superstitious conclusions about the stock and flow time series above by breaking them into apparent episodes, but that’s quite likely to mislead unless you’re thinking explicitly about the bathtub. Looking at a stock-flow scatter plot, it appears that there is no relationship: