Ever since the housing market fell apart, I’ve been meaning to write about some excellent work on federal financial guarantee programs, by colleagues Jim Hines (of TUI fame) and Jim Thompson.

Designing Programs that Work.

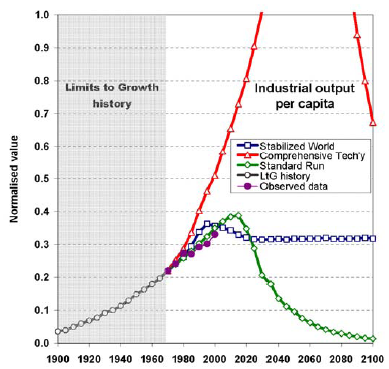

This document is part of a series reporting on a study of tederal financial guarantee programs. The study is concerned with how to design future guarantee programs so that they will be more robust, less prone to problems. Our focus has been on internal (that is. endogenous) weaknesses that might inadvertently be designed into new programs. Such weaknesses may be described in terms of causal loops. Consequently, the study is concerned with (a) identifying the causal loops that can give rise to problematic behavior patterns over time, and (b) considering how those loops might be better controlled.

Their research dates back to 1993, when I was a naive first-year PhD student, but it’s not a bit dated. Rather, it’s prescient. It considers a series of design issues that arise with the creation of government-backed entities (GBEs). From today’s perspective, many of the features identified were the seeds of the current crisis. Jim^2 identify a number of structural innovations that control the undesirable behaviors of the system. It’s evident that many of these were not implemented, and from what I can see won’t be this time around either.

There’s a sophisticated model beneath all of this work, but the presentation is a nice example of a nontechnical narrative. The story, in text and pictures, is compelling because the modeling provided internal consistency and insights that would not have been available through debate or navel rumination alone.

I don’t have time to comment too deeply, so I’ll just provide some juicy excerpts, and you can read the report for details:

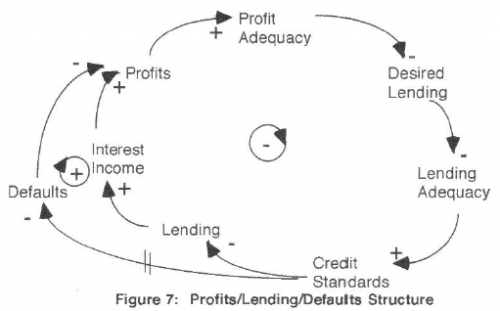

The profit-lending-default spiral

The situation described here is one in which an intended corrective process is weakened or reversed by an unintended self-reinforcing process. The corrective process is one in which inadequate profits are corrected by rising income on an increasing portfolio. The unintended self-reinforcing process is one in which inadequate profits are met with reduced credit standards which cause higher defaults and a further deterioration in profits. Because the fee and interest income lrom a loan begins to be received immediately, it may appear at first that the corrective process dominates, even if the self-reinforcing is actually dominant. Managers or regulators initially may be encouraged by the results of credit loosening and portfolio building, only to be surprised later by a rising tide of bad news.

As is typical, some well-intentioned policies that could mitigate the problem behavior have unpleasant side-effects. For example, adding risk-based premiums for guarantees worsens the short-term pressure on profits when standards erode, creating a positive loop that could further drive erosion.