Geoffrey Miller wonders why we haven’t met aliens. I think his proposed answer has a lot to do with the state of the world and why it’s hard to sell good modeling.

I don’t know why this 2006 Seed article bubbled to the top of my reader, but here’s an excerpt:

The story goes like this: Sometime in the 1940s, Enrico Fermi was talking about the possibility of extraterrestrial intelligence with some other physicists. … Fermi listened patiently, then asked, simply, “So, where is everybody?” That is, if extraterrestrial intelligence is common, why haven’t we met any bright aliens yet? This conundrum became known as Fermi’s Paradox.

It looks, then, as if we can answer Fermi in two ways. Perhaps our current science over-estimates the likelihood of extraterrestrial intelligence evolving. Or, perhaps evolved technical intelligence has some deep tendency to be self-limiting, even self-exterminating. …

I suggest a different, even darker solution to the Paradox. Basically, I think the aliens don’t blow themselves up; they just get addicted to computer games. They forget to send radio signals or colonize space because they’re too busy with runaway consumerism and virtual-reality narcissism. …

The fundamental problem is that an evolved mind must pay attention to indirect cues of biological fitness, rather than tracking fitness itself. This was a key insight of evolutionary psychology in the early 1990s; although evolution favors brains that tend to maximize fitness (as measured by numbers of great-grandkids), no brain has capacity enough to do so under every possible circumstance. … As a result, brains must evolve short-cuts: fitness-promoting tricks, cons, recipes and heuristics that work, on average, under ancestrally normal conditions.

The result is that we don’t seek reproductive success directly; we seek tasty foods that have tended to promote survival, and luscious mates who have tended to produce bright, healthy babies. … Technology is fairly good at controlling external reality to promote real biological fitness, but it’s even better at delivering fake fitness—subjective cues of survival and reproduction without the real-world effects.

Fitness-faking technology tends to evolve much faster than our psychological resistance to it.

… I suspect that a certain period of fitness-faking narcissism is inevitable after any intelligent life evolves. This is the Great Temptation for any technological species—to shape their subjective reality to provide the cues of survival and reproductive success without the substance. Most bright alien species probably go extinct gradually, allocating more time and resources to their pleasures, and less to their children. They eventually die out when the game behind all games—the Game of Life—says “Game Over; you are out of lives and you forgot to reproduce.”

I think the shorter version might be,

The secret of life is honesty and fair dealing… if you can fake that, you’ve got it made. – Attributed to Groucho Marx

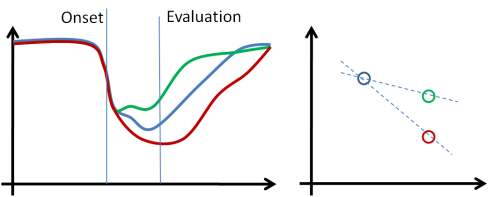

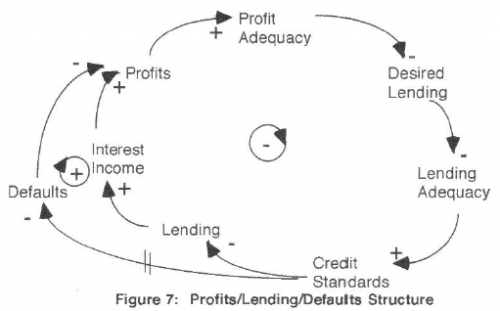

The general problem for corporations and countries is that there’s a big problem attributing success to individuals. People rise in power, prestige and wealth by creating the impression of fitness, rather than creating any actual fitness, as long as there are large stocks that separate action and result in time and space and causality remains unclear. That means that there are two paths to oblivion. Miller’s descent into a self-referential virtual reality could be one. More likely, I think, is sinking into a self-deluded reality that erodes key resource stocks, until catastrophe follows – nukes optional.

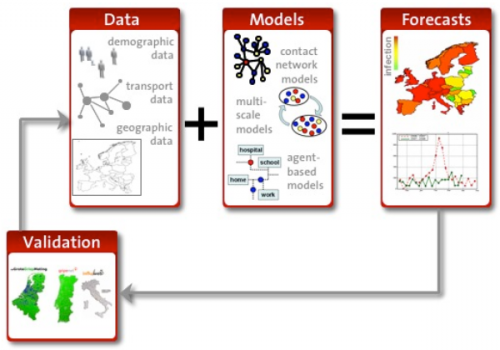

The antidote for the attribution problem is good predictive modeling. The trouble is, the truth isn’t selling very well. I suspect that’s partly because we have less of it than we typically think. More importantly, though, leaders who succeeded on BS and propaganda are threatened by real predictive power. The ultimate challenge for humanity, then, is to figure out how to make insight about complex systems evolutionarily successful.