Like spreadsheets, open-loop models are popular but flawed tools. An open loop model is essentially a scenario-specification tool. It translates user input into outcomes, without any intervening dynamics. These are common in public discourse. An example turned up in the very first link when I googled “regional growth forecast”:

The growth forecast is completed in two stages. During the first stage SANDAG staff produces a forecast for the entire San Diego region, called the regionwide forecast. This regionwide forecast does not include any land use constraints, but simply projects growth based on existing demographic and economic trends such as fertility rates, mortality rates, domestic migration, international migration, and economic prosperity.

In other words, there’s unidirectional causality from inputs to outputs, ignoring the possible effects of the outputs (like prosperity) on the inputs (like migration). Sometimes such scenarios are useful as a starting point for thinking about a problem. However, with no estimate of the likelihood of realization of such a scenario, no understanding of the feedback that would determine the outcome, and no guidance about policy levers that could be used to shape the future, such forecasts won’t get you very far (but they might get you pretty deep – in trouble).

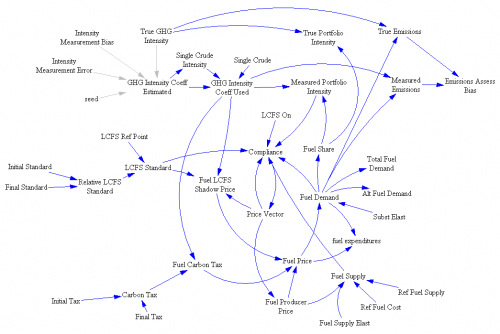

The key question for any policy, is “how do you get there from here?” Models can help answer such questions. In California, one key part of the low-carbon fuel standard (LCFS) analysis was VISION-CA. I wondered what was in it, so I took it apart to see. The short answer is that it’s an open-loop model that demonstrates a physically-feasible path to compliance, but leaves the user wondering what combination of vehicle and fuel prices and other incentives would actually get consumers and producers to take that path.

First, it’s laudable that the model is publicly available for critique, and includes macros that permit replication of key results. That puts it ahead of most analyses right away. Unfortunately, it’s a spreadsheet, which makes it tough to know what’s going on inside.

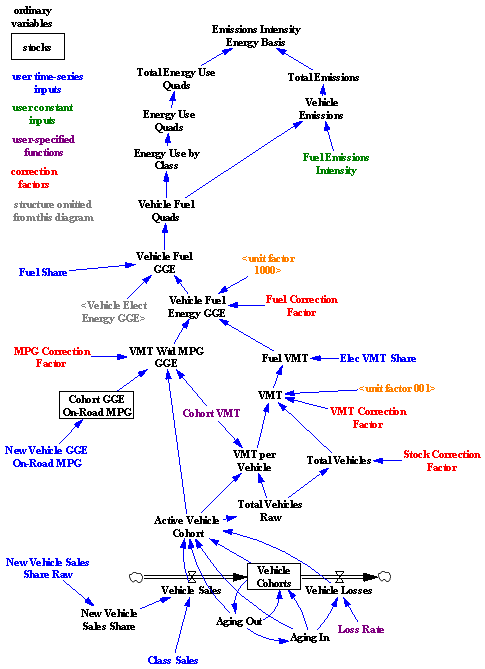

I translated some of the model core to Vensim for clarity. Here’s the structure:

Bringing the structure into the light reveals that it’s basically a causal tree – from vehicle sales, fuel efficiency, fuel shares, and fuel intensity to emissions. There is one pair of minor feedback loops, concerning the aging of the fleet and vehicle losses. So, this is a vehicle accounting tool that can tell you the consequences of a particular pattern of new vehicle and fuel sales. That’s already a lot of useful information. In particular, it enforces some reality on scenarios, because it imposes the fleet turnover constraint, which imposes a delay in implementation from the time it takes for the vehicle capital stock to adjust. No overnight miracles allowed.

What it doesn’t tell you is whether a particular measure, like an LCFS, can achieve the desired fleet and fuel trajectory with plausible prices and other conditions. It also can’t help you to decide whether an LCFS, emissions tax, or performance mandate is the better policy. That’s because there’s no consumer choice linking vehicle and fuel cost and performance, consumer knowledge, supplier portfolios, and technology to fuel and vehicle sales. Since equilibrium analysis suggests that there could be problems for the LCFS, and disequilibrium generally makes things harder rather than easier, those omissions are problematic.