I just had my house appraised for a refinance. The appraisal came in at least 20% below my worst-case expectation of market value. The basis of the judgment was comps, about which the best one could say is that they’re in the same county.

I could be wrong. But I think it more likely that the appraisal was rubbish. Why did this happen? I think it’s because real estate appraisal uses unscientific methods that would not pass muster in any decent journal, enabling selection bias and fudge factors to dominate any given appraisal.

When the real estate bubble was on the way up, the fudge factors all provided biased confirmation of unrealistically high prices. In the bust, appraisers got burned. They didn’t learn that their methods were flawed; rather they concluded that the fudge factors should point down, rather than up.

Here’s how appraisals work:

A lender commissions an appraisal. Often the appraiser knows the loan amount or prospective sale price (experimenters used to double-blind trials should be cringing in horror).

The appraiser eyeballs the subject property, and then looks for comparable sales of similar properties within a certain neighborhood in space and time (the “market window”). There are typically 4 to 6 of these, because that’s all that will fit on the standard appraisal form.

The appraiser then adjusts each comp for structure and lot size differences, condition, and other amenities. The scale of adjustments is based on nothing more than gut feeling. There are generally no adjustments for location or timing of sales, because that’s supposed to be handled by the neighborhood and market window criteria.

There’s enormous opportunity for bias, both in the selection of the comp sample and in the adjustments. By cherry-picking the comps and fiddling with adjustments, you can get almost any answer you want. There’s also substantial variance in the answer, but a single point estimate is all that’s ever reported.

Here’s how they should work:

The lender commissions an appraisal. The appraiser never knows the price or loan amount (though in practice this may be difficult to enforce).

The appraiser fires up a database that selects lots of comps from a wide neighborhood in time and space. Software automatically corrects for timing and location by computing spatial and temporal gradients. It also automatically computes adjustments for lot size, sq ft, bathrooms, etc. by hedonic regression against attributes coded in the database. It connects to utility and city information to determine operating costs – energy and taxes – to adjust for those.

The appraiser reviews the comps, but only to weed out obvious coding errors or properties that are obviously non-comparable for reasons that can’t be adjusted automatically, and visits the property to be sure it’s still there.

The answer that pops out has confidence bounds and other measures of statistical quality attached. As a reality check, the process is repeated for the rental market, to establish whether rent/price ratios indicate an asset bubble.

If those tests look OK, and the answer passes the sniff test, the appraiser reports a plausible range of values. Only if the process fails to converge does some additional judgment come into play.

There are several patents on such a process, but no widespread implementation. Most of the time, it would probably be cheaper to do things this way, because less appraiser time would be needed for ultimately futile judgment calls. Perhaps it would exceed the skillset of the existing population of appraisers though.

It’s bizarre that lenders don’t expect something better from the appraisal industry. They lose money from current practices on both ends of market cycles. In booms, they (later) suffer excess defaults. In busts, they unnecessarily forgo viable business.

To be fair, fully automatic mass appraisal like Zillow and Trulia doesn’t do very well in my area. I think that’s mostly lack of data access, because they seem to cover only a small subset of the market. Perhaps some human intervention is still needed, but that human intervention would be a lot more effective if it were informed by even the slightest whiff of statistical reasoning and leveraged with some data and computing power.

Update: on appeal, the appraiser raised our valuation 27.5%. Case closed.

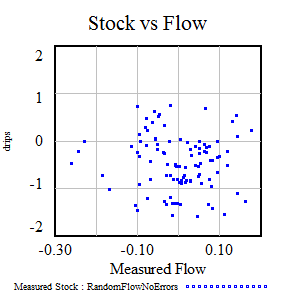

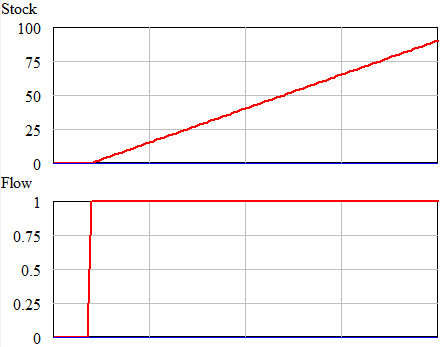

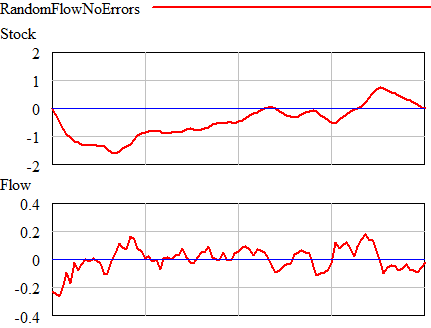

Once could actually draw some superstitious conclusions about the stock and flow time series above by breaking them into apparent episodes, but that’s quite likely to mislead unless you’re thinking explicitly about the bathtub. Looking at a stock-flow scatter plot, it appears that there is no relationship:

Once could actually draw some superstitious conclusions about the stock and flow time series above by breaking them into apparent episodes, but that’s quite likely to mislead unless you’re thinking explicitly about the bathtub. Looking at a stock-flow scatter plot, it appears that there is no relationship: