Bloomberg reports that California’s cap and trade program may still be some way off:

[CARB chair] Nichols told venture capitalists and clean-energy executives last week in Mountain View, California, that she was “thinking of punting,” saying the specifics of the emissions-trading program may not be ready for 1-2 more years.

“I think the cap-and-trade system needs to be thought through and I don’t think that has been done yet,” said Jerry Hill, a member of the Air Resources Board. “It would be a good idea to take our time to be sure what we do create is successful.”

Greentech VCs aren’t thrilled, but I think this is wise, and applaud CARB for recognizing the scale of the design task rather than launching a half-baked program. Still, delay is costly, and design complexity contributes to delay. California has a lot of balls in the air, with a hybrid design involving a dozen or so sectoral initiatives, a low-carbon fuel standard, and cap & trade. As I said a while ago,

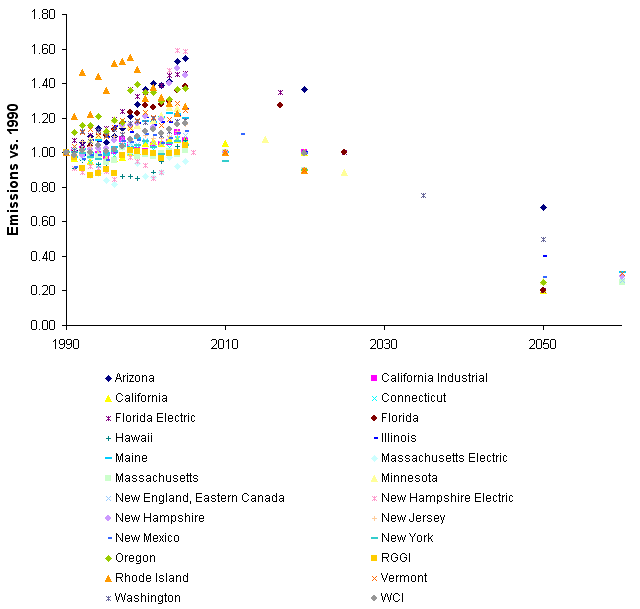

My fear is that the analysis of GHG initiatives will ultimately prove overconstrained and underpowered, and that as a result implementation will ultimately crumble when called upon to make real changes (like California’s ambitious executive order targeting 2050 emissions 80% below 1990 levels). California’s electric power market restructuring debacle jumps to mind. I think underpowered analysis is partly a function of history. Other programs, like emissions markets for SOx, energy efficiency programs, and local regulation of criteria air pollutants have all worked OK in the past. However, these activities have all been marginal, in the sense that they affect only a small fraction of energy costs and a tinier fraction of GDP. Thus they had limited potential to create noticeable unwanted side effects that might lead to damaging economic ripple effects or the undoing of the policy. Given that, it was feasible to proceed by cautious experimentation. Greenhouse gas regulation, if it is to meet ambitious goals, will not be marginal; it will be pervasive and obvious. Analysis budgets of a few million dollars (much less in most regions) seem out of proportion with the multibillion $/year scale of the problem.

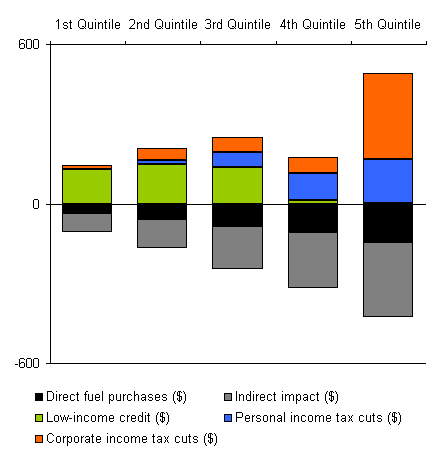

One result of the omission of a true top-down design process is that there has been no serious comparison of proposed emissions trading schemes with carbon taxes, though there are many strong substantive arguments in favor of the latter. In California, for example, the CPUC Interim Opinion on Greenhouse Gas Regulatory Strategies states, ‘We did not seriously consider the carbon tax option in the course of this proceeding, due to the fact that, if such a policy were implemented, it would most likely be imposed on the economy as a whole by ARB.’ It’s hard for CARB to consider a tax, because legislation does not authorize it. It’s hard for legislators to enable a tax, because a supermajority is required and it’s generally considered poor form to say the word ‘tax’ out loud. Thus, for better or for worse, a major option is foreclosed at the outset.

At the risk of repeating myself,

The BC tax demonstrates a huge advantage of a carbon tax over cap & trade: it can be implemented quickly. The tax was introduced in the Feb. 19 budget, and switched on July 1st. By contrast, the WCI and California cap & trade systems have been underway much longer, and still are no where near going live.

My preferred approach to GHG regulation would be, in a nutshell: (a) get a price on emissions ASAP, in as simple and stable a way as possible; if you can’t have a tax, design cap & trade to look like a tax (b) get other regions to harmonize (c) then do all that other stuff: removing institutional barriers to change, R&D, efficiency and renewable incentives, in roughly that order (c) dispense with portfolio standards and other mandates unless (a) through (c) aren’t doing the job.